Why megalodons have captured our imagination and what researchers have learned from their extinction

Before great white sharks, megalodons ruled the oceans. What researchers have learned about these apex predators and their extinction.

Listen 5:24

A megalodon shark's tooth is passed around a tour group at the Mound City Group at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park in Chillicothe, Ohio. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

There’s something simultaneously glorious and terrifying about megalodons. It’s difficult to visualize the largest shark to ever exist, with its size ranging from 40 to 70 feet long. That’s about the size of two school buses and more than three times the length of a great white shark. Picture a shark tooth bigger the size of your hand.

How megalodon became so large

Otodus Megalodon, commonly known as megalodon, was truly a feat of nature. Endowed with a trait called regional endothermy, or partial warm-bloodedness, this trait allowed these sharks to become massive. Regional endothermy means their internal body temperature was warmer than the water in the surrounding seawater.

“To maintain that regional endothermy, the shark just had to keep eating more and more,” said Phillip Sternes, a shark researcher at the University of California at Riverside. He researches why extinct and extant sharks look the way they do.

To maintain their endothermy, megalodons had to eat a lot. And we’re talking a lot. Their prey included small to medium-sized cetaceans, the order of aquatic mammals including dolphins, porpoises, and whales. Megalodon bite marks have been found on the vertebral fossils of now-extinct carnivorous whales.

Why did megalodon go extinct?

Around 3.5 million years ago, when the climate started to change, the presence of the great white, along with the decline of megalodon’s prey, presented challenges for this massive fish.

Jack Cooper, a PhD student at Swansea University in the UK, studies shark fossils. He said the great white shark’s evolution, alongside the megalodon’s extinction, isn’t a coincidence.

“About three million years ago, [when] megalodon was going extinct, we have detected sea level oscillations, which would have really ruined all the coastal habitats.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

These changes in sea level disrupted potential nursery areas where megalodon pups were living. Not only does this mean less habitat for the shark, but also less prey availability. For such large animals, finding enough sustenance is vital.

“At the same time, the great white was starting to evolve and may have potentially been outcompeting the smaller megalodons. So, we think it was probably down to a combination of less prey availability, more competition, and less, and less habitat which ultimately led to megalodon’s extinction,” Cooper said.

Shark researcher Phillip Sternes says that, “if the water is getting cooler, that means you’re going to have to eat even more food to keep your body temperature up because that environmental stress or cold water is going to be hard on the body. So you’re going to have to eat even more food.”

So these massive sharks went extinct for a variety of reasons, and having smaller, faster competitors, like great whites, among others, was definitely a threat.

Caveats to comparisons

For a long time, researchers believed that megalodons were ancestors to modern great whites. A fair assumption, considering the two have similarly shaped serrated triangular teeth, regional endothermy, and both had similar palettes for marine mammals.

However, in the 1990s, researchers discovered that great whites and megalodons aren’t directly related but ecological analogues: “not necessarily a relative, but more like a distant cousin that was quite similar,” Cooper said.

Understanding that these two are more like “distant cousins” and not direct relatives is quite important since scientists don’t have any complete fossils of megalodons.

Because shark skeletons are made of cartilage, which doesn’t fossilize, everything we know about the megalodon comes from numerous teeth, protected by their enamel and one well-preserved vertebral column in Belgium.

This means that without much in the fossil record, scientists make predictions about what megalodon could have looked like based on sharks like great whites, among others.

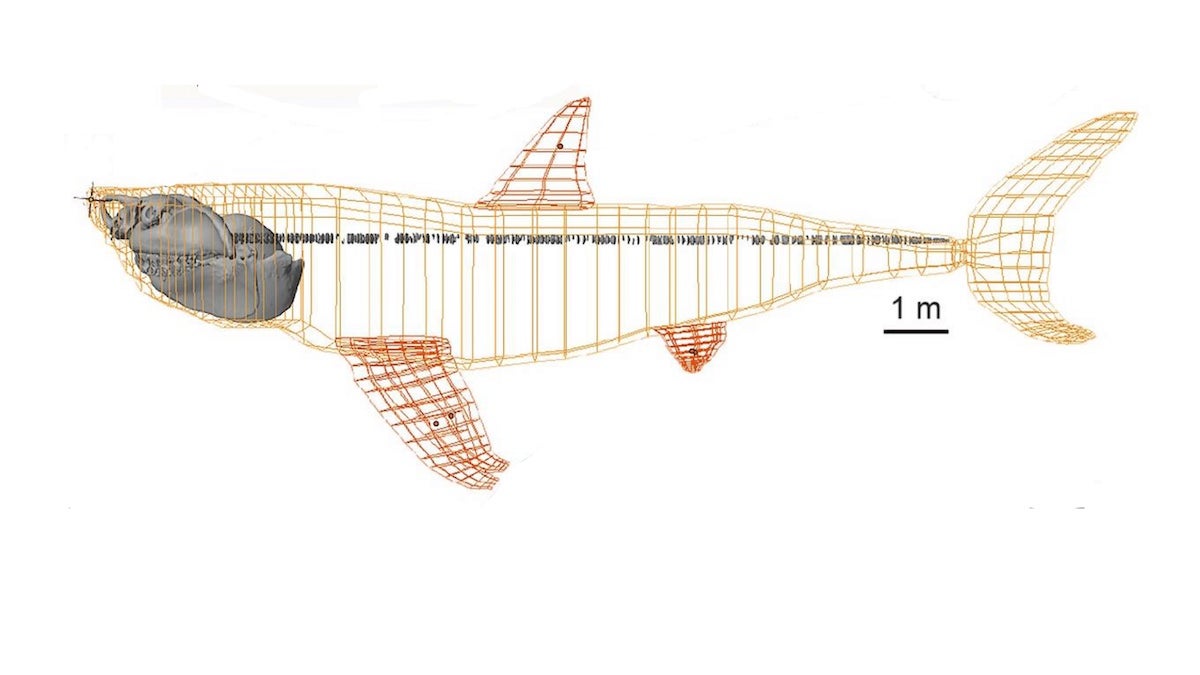

Cooper worked with other scientists to produce the first-ever 3D rendering of megalodon.

“There’s about 140 of their vertebrae or backbone that came from one individual. So, by 3D modeling that entire vertebrae and using that as the basis for our shark’s size, and then filling in some gaps.”

For the “gaps” Cooper used the great white and other similar sharks for reference.

“We can essentially use free animation and modeling software … to fit hoops around those skeletal elements and produce the overall body shape of megalodon.”

After rendering the megalodon, Cooper was also able to determine volume, body mass, its speed, the size of its stomach. Their calculation predicts that the megalodon’s stomach could fit up to 10,000 liters — the size of an entire orca whale.

But some researchers like Sternes, expressed hesitation about modeling when there isn’t enough evidence in the fossil record, especially knowing that the great white and megalodon aren’t directly related.

“The great white makes sense because of the tooth shape and diet, but at the same time, the sheer size difference between the two — I think causes issues in the body shape reconstruction,” Sternes said.

Keeping the study of fossil sharks alive

Cooper says the fate of megalodon can carry important lessons for understanding the extinction of an apex predator on our ecosystem.

“Over a third of shark species are facing extinction at the moment, with overfishing being the primary threat they’re facing now, which is something that megalodon and other extinct sharks simply wouldn’t have faced while they were around,” Cooper said.

He says studying the ecological effects of megalodons extinction is extremely important for understanding what would happen if apex predators that exist today, like great whites, went extinct.

“If we can understand the extinction of that animal and what effects that had on the wider marine ecosystem, then that gives us something to anticipate and to understand how ecologically our oceans could change if we lose today’s sharks.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.