Maggots: A vile prescription

Doctors are trained to remove maggots from patients, but could it be that maggots are actually there to help?

Listen 08:55

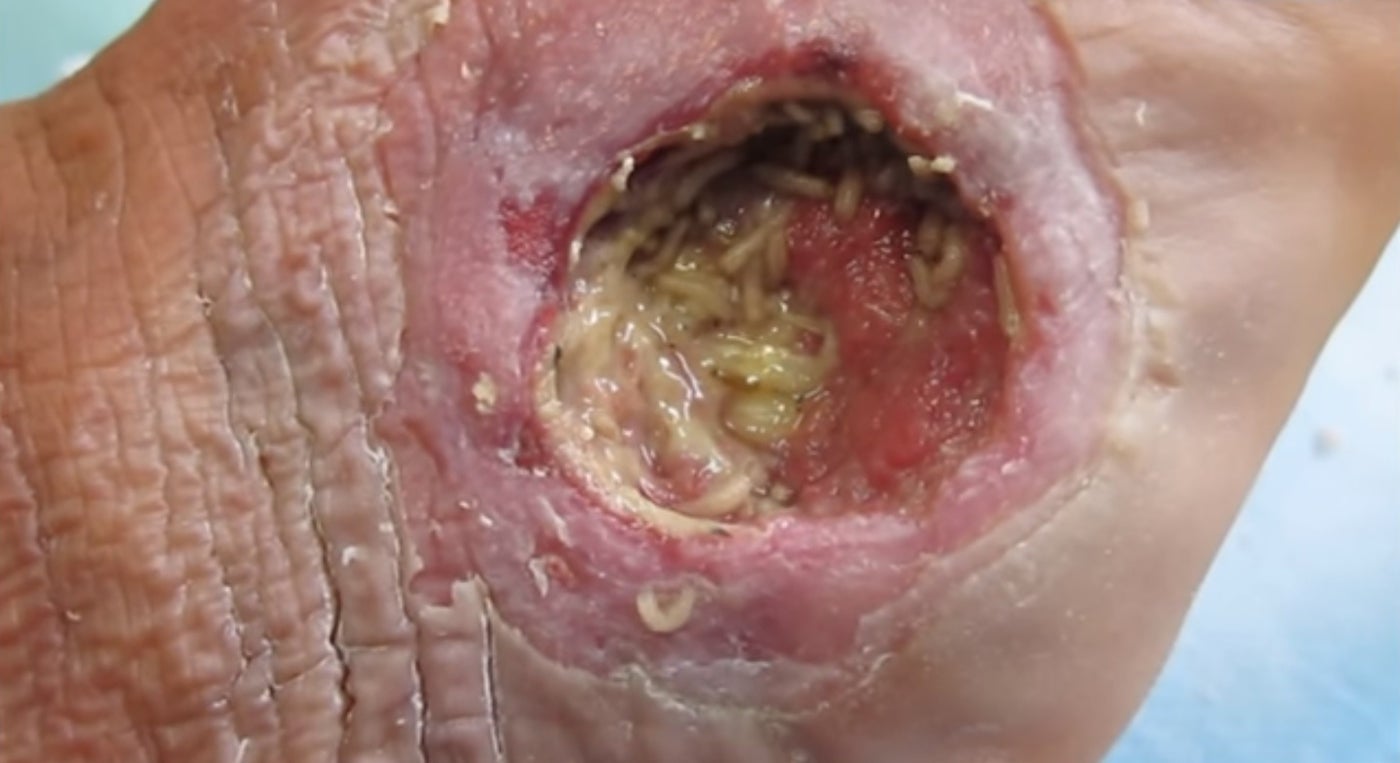

Doctors are trained to remove maggots from patients' wounds, but could it be that maggots are actually there to help? (Tsekhmister/Bigstock)

Maggots, those white, squirmy, wormy things, are the larval form of the Diptera species. In other words, they are baby flies. It turns out they really thrive in chronic, poorly healing wounds — they’re perfect places for maggots to grow. And all it takes is for one fly to land on a wound for a few seconds. It can lay hundreds of eggs.

Kelli Outlaw is an ER physician in Maryland. She was treating a man who had wounds on his legs. His bandages hadn’t been changed in weeks.

“As I’m unwrapping, I just see movement on his legs. I realize it’s maggots!”

There were thousands of them, just wiggling back and forth. Outlaw says she screamed and dropped her scissors, and her supervising attending came running in. ”And she’s like, ‘Oh, it’s just maggots.’ ”

Outlaw diligently cleaned every last maggot from the wound. And that became a topic of ER watercooler discussions: What’s the best way to get rid of maggots?

Physician assistant Kevin Nelson likes to irrigate the wound. “If you take a ziplock bag and cut a hole in it, then you can push water through that. Also using suction to pull them out of the area.”

Naim Ballout, who works for Doctors Without Borders, swears by this recipe: “The best mixture is to use two vials of sodium bicarb, have 500 cc of normal saline, 500 cc of hydrogen peroxide, 250 cc of Betadine.”

And I asked plastic surgeon Amit Mitra — well, he’s my dad, full disclosure. He likes ethyl chloride spray. “I spray it over the wound where the maggots are, and maggots actually fall off.”

As for me? Well, I think maybe we should just leave them there. Actually, I might even prescribe them. Let me explain.

Diana Dupuy had foot surgery for a bunion and an unhealed fracture. The surgery went well, but, according to Dupuy, “when they took the cast off, and I looked at my foot, you’ll see those black, necrotic wounds, and when I saw that, I was like, `Oh my goodness!’ I knew that wasn’t good.”

Wounds like hers are called poorly healing wounds. They’re common in diabetics, but can happen to anyone — and, for whatever reason, there’s not enough blood flow to the wounded area. As a result, instead of forming a scab and healing, tissue in the wound starts to die. This is called necrosis. “So weeks had gone by, and the wound looks worse and worse. The necrotic wound started oozing, it looked infected, it looked nasty,” Dupuy says.

Necrotic tissue is a perfect place for bacteria to grow, because without blood flow there, all your natural defenses can’t get to it. It’s a no man’s land. Over time, the bacteria spread, and the necrosis expands. Eventually, the bacteria use the dead tissue as a launching pad to infect the rest of you, making you septic and eventually killing you.

The standard treatment for this is to grab a scalpel and cut away as much of the dead tissue as possible. That’s called debridement. Then you need to take antibiotics to keep the bacteria at bay. And finally you have to dress the wound and keep it as clean as possible. I can tell you, it’s crude, it ain’t pretty, but it’s what you gotta do.

But for Dupuy, it didn’t work. In fact, her wound kept getting worse. “It was at that point I realized, I’m in danger of getting a bone infection, which could cause them to amputate my foot.”

In her desperation, she remembered a lecture she had heard while earning her degree in clinical laboratory science. It was about medical maggots. Her search brought Dupuy to entomologist and physician Ron Sherman, who says he was interested in how insects relate to diseases, usually by causing diseases.

But what if insects could prevent disease? Mentions of maggots in wounds date back thousands of years, and a French surgeon in Napoleon’s army noted that war wounds that had maggots seemed to fare better than those that didn’t. Doctors during the Civil War made similar observations. But no one had really studied this.

So Sherman studied poorly healing pressure ulcers and showed that, using maggots, 80 percent of the wounds were free of dead tissue compared to 48 percent using traditional therapy. In addition, wounds healed at a faster rate. Because of his research, the Food and Drug Administration actually approved the use of maggots as a medical device in 2004. It was the first time a living creature had been granted FDA approval. Sherman started a company called Monarch Labs, to sell medical grade, sterile maggots.

Fast-forward 10 years, and Dupuy has a fresh shipment of maggots that her doctor is, skeptically, getting ready to apply to her foot. She recalls, “I didn’t know how I was going to respond to them, I didn’t know if it was going to make me vomit, pass out and [get] dizzy.

The doctor applied a gauze pad full of maggots to the wound, and covered it with a breathable dressing. “Maggots that stayed in my wound, they’re hungry right, they immediately started doing their work. It seemed like when I calmed down, they calmed down. Because I was panicked, I was like, `Oh my god, look at all these maggots!’ ”

To her surprise, Dupuy wasn’t grossed out. The maggots feasted in the wound for about two days.

“What you do feel,” she remembers, “is them getting bigger, and they wiggle. You can feel them wiggling around.” So every few days, the dressing would be changed, the bigger maggots removed, and a new batch put in. She did a few sessions like this.

“After the first dose, the slough looked like it was almost 75 percent gone. And that was in just 48 hours,” she says. And now, her foot is “perfect,” according to Dupuy. “I can wear stiletto high heel shoes, I ride a motorcycle, it’s perfect.”

Dupuy experienced a true symbiotic relationship with the maggots. Well, at least until their work was done. “I felt bad how I had to kill them when I released them. Here they’re doing this great treatment to me, and the reward is death.”

So, how are these maggots doing a better job with Dupuy’s foot than we are as doctors? Liya Davidov is a doctor of pharmacy, and she studied this.

“You put those immature, basically baby flies into the wound, and basically just like any baby they need to feed. And their food is dead tissue.” So point number one is, the baby maggots feed on dead, rotting flesh. The same dead flesh that is causing so much trouble in our chronic, necrotic wound. To accomplish this, they crawl around the wound, looking for the most rotten parts. They have little rough spines on their skin, and so as they crawl, they rake the tissue. This loosens the dirt, so to speak, and separates dead tissue from the living tissue. It’s more gentle than the scalpel, and it’s more precise.

Then, they need to eat this tissue, Davidov says. “You know how the babies drink milk, they can’t have a steak? This is kind of along the same lines.” Baby flies need their food broken down too, so they secrete their digestive enzymes onto the wound. These enzymes liquefy the tissue and turn it into a slough. “And then they basically just snort it up.”

The crazy thing is that these enzymes only affect the dead tissue. The living tissue doesn’t dissolve. And, says Davidov, “In the process of doing it, they are also eating up all the bacteria.” Maggots don’t want to die from bacteria either. So their stomachs have evolved to be able to kill bacteria, even some of the most resistant ones out there. In addition, they release unique chemicals onto the wound that cause bacteria to die.

So, the maggot is debriding better than a surgeon, killing germs better than any antibiotic, and as if that wasn’t enough, they somehow seem to accelerate tissue and vascular regrowth. And yet, maggot therapy is still rarely used. According to Sherman, “less than 5 percent of patients who are destined for amputation are given a trial of maggot therapy, even though published studies show that 50 to 70 percent of those amputations could probably be prevented.”

There are some caveats: The maggots ought to be sterile, and not all species work the same. Most practitioners, including Sherman, agree that you should try the standard way first.

There can be some pain. And, Davidov says, “Patients do have anxiety, which makes sense because people find it gross. I mean, It’s yucky, you put something living on your body, it grosses people out.”

It’s yucky, it’s gross … but sometimes, it might be just what the doctor ordered.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.