Is it possible to ‘treat’ poverty for better health?

Listen

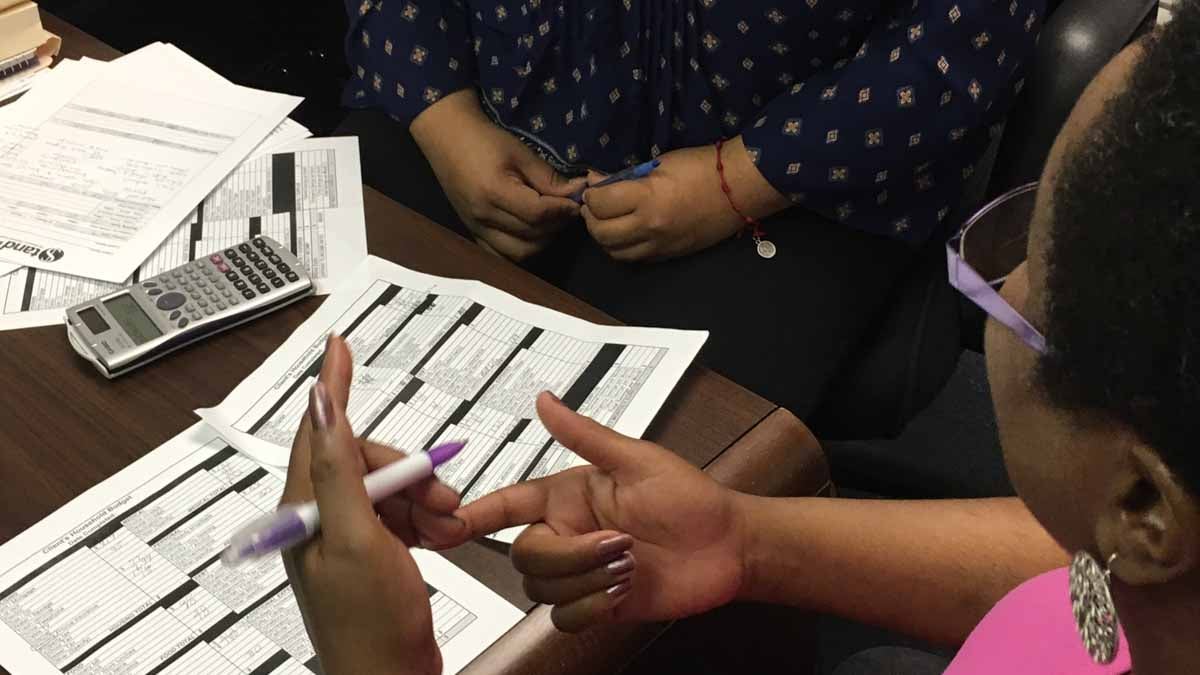

Vanessa Moore and her budget coach sit down and talk through Moore's finances. (Taunya English/WHYY)

Vanessa Moore’s checking account is $500 overdrawn. She also has a rainy day, emergency bank account—with $34 in it.

A few years back, she went through a costly divorce and had to leave her home—because the mortgage was in her husband’s name. After that, Moore missed lots of work because of depression, back pain and fibromyalgia. Eventually she lost her job. Then last year, she found a lump in her breast.

“I don’t know where it came from but I know I’ve been under a lot of stress the last six years,” she said.

Moore finished breast-cancer treatment this summer, and she’s on the rebound. Now she’s trying to mend her financial health.

She and budget coach Maria Luna-Medina are creating a household budget and looking for ways to cut back on spending.

Moore had shoulder-length hair before chemotherapy, now she sports a short afro—and even that small expense gets recorded.

“My son is like, Ma, you need a shape up, so I had to go to the barber and that was $10,” Moore said.

She’s learning to balance income and spending in a financial empowerment program called Stand By Me. Delaware sponsors the coaching.

State governments spend hundreds of millions of dollars on safety-net benefits for low-income residents, and nearly everywhere, the costliest public assistance is Medicaid—health care for the poor. In Delaware, offering money-management training is part of a plan to do more than help poor people in crisis. Financial empowerment is designed to launch them toward financial stability.

And maybe, just maybe—in the long run—the state saves money, too.

Sitting side-by-side with a calculator between them, Moore and coach Luna-Medina, discovered a surplus $193 in Moore’s monthly budget. But that’s on paper. In real life, money is tight. When Moore is waiting for her social-security disability check to arrive—and the rent is due–she sometimes takes out a payday loan to make it to the end of the month.

Moore and her 15 year old were homeless for a short time, and they moved several times in recent years looking for an affordable apartment.

“I’m barely affording where we are,” Moore said. “But we’re making it.”

But it’s not a completely healthy situation. She found a mushroom in the bathroom, and she says it smells of mold and spoiled water when it rains.

Moore is resourceful. She applied for financial aid to pay for school supplies for her son. She wrote a letter to the United Way for help—and was connected to Delaware’s financial empowerment program. She’s learning how to scrimp; it’s rare for she and her son to have dinner out or go to a ball game.

Being poor is a tough cycle to break. Moore feels the pressure and she’s worried about her son.

“He deals with this situation the best he can. He grew out of a pair of sneakers at the end of the school year, and instead of stressing me out about the sneakers, he took the insoles out of his sneakers, and he’s been wearing them all summer,” she said.

“Part of our goal here with Vanessa is that she is able to control her money rather than her budget controlling what she is able to do,” said Luna-Medina.

Upstream problems

Public health professionals often use the analogy of fish in a river to explain the connections between poverty and health.

“You look downstream and you see that the fish are dying because the water is polluted; your intervention might be to clean up the water in the immediate vicinity of where the fish are dying,” said Jason Purnell, a health-disparities professor in St. Louis, at Washington University’s Brown School of Social Work and Public Health.

He says a better strategy is to find out where the pollution starts. To help a whole community of unhealthy people, you have to consider the upstream problems–neighborhood influences and social policies that poison health.

Racial segregation is one example. Denying home loans based on race isn’t legal, but Purnell says discriminatory lending practices happen, a lot.

Owning a home is one way low-income people move out of poverty. Justice-Department investigations show that it is still harder for equally qualified African Americans and Hispanics to get a mortgage. That leaves some groups cut off from wealth building and stuck in neighborhoods that are less likely to have nutritious food or safe parks where kids can play.

Purnell says the consequences reach into the next generation. Stressed-out people often use unhealthy habits—like smoking, overeating or watching too much TV—to cope.

“There’s something about the insult of poverty and stress to the developing child that is lingering and permanent,” Purnell said.

Purnell says financial health is public health, but he and other believers are still trying to educate the public and convince some lawmakers. In St. Louis he leads a community-academic project called For the Sake of All, which is working to improve African American health.

“Really, take the conversation beyond this notion of medical care and personal responsibility,” he said.

Small fixes

So far, there’s not a lot of proof that you can ‘treat’ conditions of poverty to save health care dollars.

Side note: Michael Reisch, professor of social justice at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, isn’t a big fan of the term ‘treat’ applied to that public health approach.

“I don’t like the verb, because it sounds like a disease,” he said. “It could lend itself to thinking of poverty–and people in poverty–as evidencing some kind of pathology.”

Socials scientists have mostly tested single solutions and small changes.

“They work best if they are coordinated with each other,” Reisch said. “Programs that are coordinated and meet the various needs of low-income people who are at higher risk for health problems are the ones that are most effective.”

It’s just not enough to provide food stamps or make home repairs—that helps, he said, but you also have to fix the environmental problems of living in a neighborhood with a lot of lead paint and old buildings next to polluting factories or where there’s lots of crime.

“Policymakers–because they do budgets and planning in the short term—are always trying to see, ‘What can we do that will have a quick fix?'” Reisch said.

Meanwhile there are long-term community-wide, comprehensive efforts underway–called ‘empowerment zones‘ and ‘promise neighborhoods.” Some of those integrated approaches have been linked to lower rates of infant mortality, less childhood obesity and fewer reports of child abuse.

“If you want to see if a baby—that’s about to be born—is going to have a better outcome and have a good life, you are not going to find that out in a few months, or a couple of years,” Reisch said. “These problems took generations to create.”

“We’ve spent the last century engineering this,” health researcher Jason Purnell said. Now it’s time to figure out how to reverse engineer policies that keep people poor and sick, he said.

On the West Coast, the California Endowment is a big investor. And in New Jersey, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation spends millions on programs and research to design healthier neighborhoods.

One recent study, funded by Robert Wood Johnson, found huge health differences in places just a few miles apart. A child born in prosperous Princeton, New Jersey –for example–can expect to live to age 87. In Trenton, New Jersey, where there’s lots of poverty, the life expectancy is 71. That disparity repeats in cities and towns across America.

Sarah Szanton, a professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, says you can’t move everyone to Princeton, New Jersey.

“But we are finding we can do things around the edges,” she said. “What is it about Princeton that is moveable to Trenton?”

Szanton is a researcher and a nurse, she says little things pile up over a lifetime, and she wants to tease out which things matter most to health.

“We are just starting to understand the factors and understand what’s fixable,” she said.

Some of those public health findings have already been translated into real-world policy. In Maryland, state lawmakers just boosted the amount of nutritional assistance available for older adults. The law was passed not too long after Hopkins researchers discovered that low-income seniors–who get food stamps–are less likely to end up in the hospital or a nursing home.

Szanton leads a project called CAPABLE, which stands for Community Aging in Place, Advancing Better Living for Elders. Not surprisingly, the ubiquitous Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is a funder.

CAPABLE sends a nurse and an occupational therapist into older people’s homes to see how seniors are living. And a handyman goes along to do home repairs.

“People get very excited about doorbells, in many cases the doorbell they’ve got doesn’t work or was taken out at some point. If an ambulance needs to come, it’s nice having a doorbell,” said Gary Felser, the research-project handyman, and construction supervisor for Civic Works in Baltimore.

He also does work for that city’s senior home-repair program.

At a 1920s bungalow in Baltimore—one of Felser’s Cities for All Ages assignments—he had a long punch list that included putting in a raised toilet seat and hanging a fire extinguisher in the kitchen.

While Felser was sweating in the Baltimore heat, homeowner Christine looked cool with her snowy-white hair pinned in a neat bun. Not much bothers the 88 year old, but she does worry about identity theft and senior scams, so she asked to use just her first name.

Christine and her husband raised six children in the home, but these days it’s hard for Christine to keep up with small repairs. Earlier this year, she almost slipped in the bathtub.

So Felser installed grab bars in the bathroom. He mounted new overhead lights leading down to the cellar basement, and put up a second, sturdier bannister, so Christine can hold on as she walks down the steep wooden stairs to do laundry.

As he finished his work, Felser joked that keeping up with her house chores will keep Christine young.

“I don’t know about that,” she said.

“Younger, how’s that?” Felser countered.

“I don’t know about that either,” Christine said. “Let me say it keeps me on the move.”

More than 400 seniors have gotten similar home-repair help through Johns Hopkins’ CAPABLE program. Participants said they are better able to do everyday tasks, such as cooking meals and getting dressed. And after working with a nurse and therapist, their strength and balance is better. Many said their depression lifted.

That’s wonderful, said study leader and public-health researcher Sarah Szanton, but it’s not enough to get insurance companies and lawmakers to invest in the program on a large scale.

“At lot of people have good ideas that never get put into action, and that’s because there’s no measurement about how much it costs and how much it saves,” she said.

So in her latest investigation, Szanton is trying to figure out if some of those fixes pay off for the health system.

The four-month CAPABLE program—including home repairs—costs about $3,000 per person. In Maryland, the average hospitalization costs $15,000.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.