Philly-area firm leads the hospital-bill fight vs. the $500 Tylenol

Listen

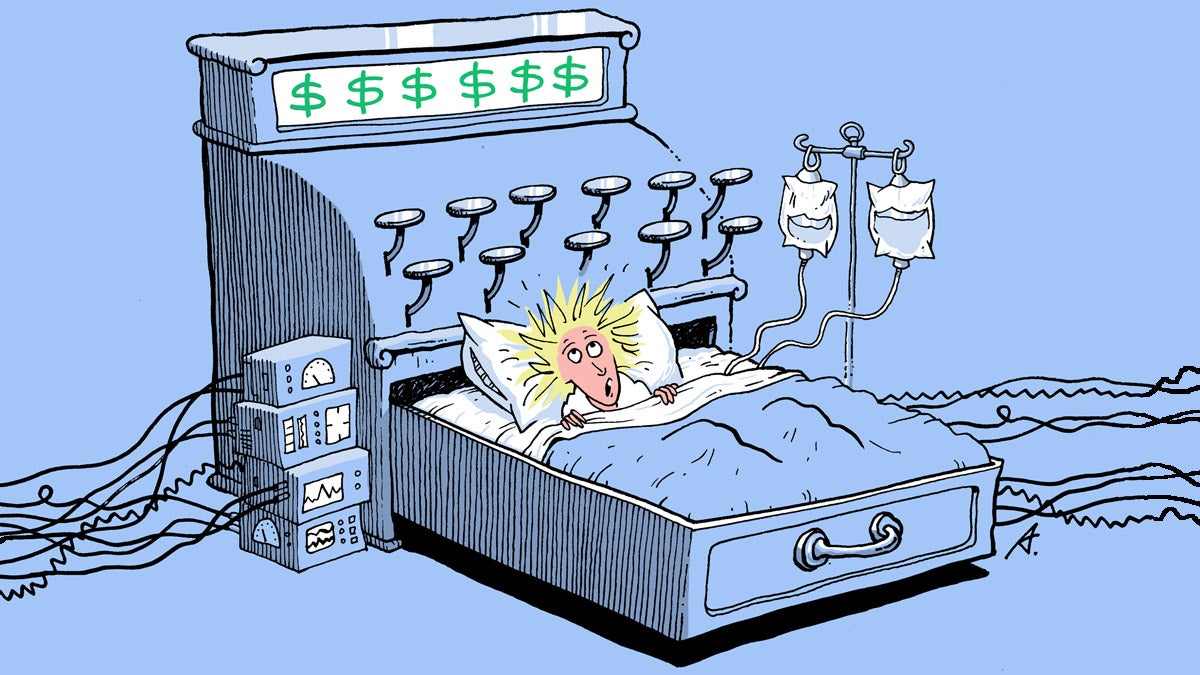

(Illustration by Tony Auth)

Medical bills are expensive and really hard to understand. The Pulse talks with a few people who are trying to change the way it’s done.

The envelope looks innocent enough, usually. But then: sticker shock.

Medical bills are expensive — and really hard to understand.

For example: Have you ever tried to find out how much a specific procedure costs — before having it? Have you ever gotten a bill where a seemingly simple pill cost several hundred dollars?

Health-care consumers often feel helpless and mystified as huge bills get batted between insurance companies and medical providers. That helplessness is especially pronounced when a single patient gets stranded between huge, seemingly indecipherable systems.

That’s what happened to Jessica Tranchina.

Newborn baby, big bills

Tranchina is a physical therapist and triathlete in Austin, Texas. A few years ago she had a son.

“I had a natural birth, completely natural, no epidural or any meds of any sort,” Tranchina said.

She and her husband had insurance. They’d met their deductible, but were still faced with staggering hospital bills. Her insurance wouldn’t cover everything (claiming the hospital charges were excessive) and the bills Jessica received were full of surprises.

“Oh my goodness, what is that?” Tranchina said, looking over an old bill. “120 milliliters of olive oil for $15. Why didn’t I bring my own?”

That, plus the big-ticket items, added up quickly. Tranchina was on the hook for roughly $11,000.

“Threat after threat from the hospital,” she recalled. “‘This is going to affect your credit, we’re going to send this off to collectors.'”

The bills languished in collections until Tranchina’s employer put her in touch with a small company outside Philadelphia. The company went through her charges, line by line, and negotiated a deal.

“We’re not trying to put our fingers in anybody’s chest,” said Steve Kelly, CEO of the company, ELAP Services. “We’re trying to make sure the patient feels supported and defended. We’re going to protect their rights.”

Line-by-line mysteries

In many ways, ELAP is on the frontlines of the war against escalating medical costs. Kelly says part of his company’s mission is to de-mystify medical bills, working to figure out a fair price for a given medical service.

The clients for whom ELAP tries to perform that magic are mostly businesses that choose to self insure – to pay for employees medical bills out of a pool of money the company sets aside each yer.

Kelly says, right now, medical billing works like this:

A hospital will essentially overcharge for its services, fully expecting the patient’s insurance company to negotiate a discount. If the price is going to be knocked down, the hospitals would say, you had better start high.

“Nobody would do business [like that] in any other area,” Kelly said. “In other words, if I said to you, ‘This chair is for sale. It’s $50,000 but I’m going to give you a 20 percent discount,’ you would laugh.”

Krista Haig also works for ELAP services. She audits medical bills for a living and has seen some doozies.

“We have seen one line for $500 for an acetaminophen tablet, which you can get from Amazon.com, an entire bottle of 500 of those, for, like, a dollar-fifty,” Haig said.

Implants, say a hip or a knee, are also a big area for inflated charges, ELAP says. Hospitals will implant one, but charge for two.

Or this example:

“Because you called a CAT scan a $6,000 expense, it doesn’t make it so,” Kelly said. “To demand $5,000 above the $1,000 you were paid for the CAT scan, which was a fair reimbursement, to demand that from an individual is egregious.”

In the weeds

The stakes here are high for ELAP clients that self-insure.

For example, Auto Dealership X has set aside a pool of money for its employees’ health claims – rather than paying a per-worker premium to an insurance company.

For the worker, it operates just the same as regular insurance; but for the company, it’s a chance to control health costs by side-stepping the steady rise of insurance premiums. But this also means running the risk that a few catastrophic medical bills could sorely deplete a given year’s self-insurance pool.

Kelly says employers choosing to self-insure is a growing niche.

“We work with them to develop rational reimbursement policies to try to shield them from the irrational process of medical billing,” Kelly said.

Basically what ELAP does is say, “Hey, hospital: our client will pay you this much for this service.” The goal is to hammer out a degree of transparency that’s otherwise unavailable.

“And there’s often quite a bit of friction,” said Kelly.

But, according to ELAP, it works about 80 percent of the time: ELAP’s 140-plus clients typically work out a deal with providers on how much a certain procedure will cost.

Seeking price transparency

Hospitals and doctors typically have different price tags for procedures depending on the payer. A network of hospitals will charge Insurance Company A one price for a CAT scan, and Government Payer B another price. Individuals get another price and Insurance Company C probably worked out its own deal. It’s really complicated.

“What one hospital charges for a specific service is not necessarily what another hospital charges for that service,” said Martin Ciccocioppo, the vice president for research at the Hospital and Health System Association of Pennsylavania.

From a hospital perspective, it’s not really about what one particular thing costs, Ciccocioppo says.

In other words, forget the $500 Tylenol tablet. All the hospital is trying to do is to make sure the eventual payments add up to enough revenuee to let the hospital stay in business.

Having a clear menu with fixed pricing is pretty much a thing of the past, Ciccocioppo says.

“Getting every payer to agree to pay a sustainable common rate for each service would be ideal — but in our marketplace, it doesn’t seem like there’s a way that we can get there,” he said.

ELAP starts its process with the prices that hospitals are required to report to the government. These Medicare reimbursement rates are the closest thing to a baseline measure of cost in the health care marketplace.

ELAP will tack on a amount over that baseline — at least 20 percent, according to Kelly — when they work with employers to strike deals with health systems.

Kelly says transparency in billing means lower health-care costs for employers. But the actual price tag for procedures is becoming more important for all health-care consumers.

The new normal?

It pays to remember the big picture here: Over half of all personal bankruptcies in the U.S. today are caused at least in part by medical debt.

And now, the medical landscape is shifting in such a way that more health-care consumers are paying more out of pocket for the care they receive.

Co-pays are on the rise, and more people have plans with high deductibles, meaning they are more likely to directly feel the pinch of inflated bills.

Jeanne Pinder is a former New York Times reporter who started the website clearhealthcosts.com to address what she saw as health care’s new normal.

“We’re a New York City-based startup bringing transparency to the health care marketplace by telling people what stuff costs,” Pinder said.

The pricing information is limited to certain markets at this point, but the idea is that people can go online and see what a common procedure will cost. Say you need a lower back MRI. If you’re in New York City, the cheapest option is $400 in Queens; the most expensive is $1,200 in Manhattan. If you want to see the other options in between, you can find how much those cost, too.

Pinder says wading through this stuff matters. She gets her numbers from the Medicare reimbursement rate, pricing surveys and crowdsourcing. She says the question of what-costs-how-much-where has to re-enter the conversation.

“We think this marketplace is broken, not just in cost transparency but also in quality transparency,” Pinder said.

It’s not that people should get the cheapest possible procedure, Pinder says. It’s that it should be easier to find out what, if anything, makes the $3,000 version better than the $300 one.

“And that’s what we all want,” said Pinder. “We don’t want the cheapest appendectomy, we want the best for the money, we want the best value.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.