How the myth of ‘patient zero’ was made

A labeling fluke and an international bestseller shaped our thinking about public health.

Listen 13:16

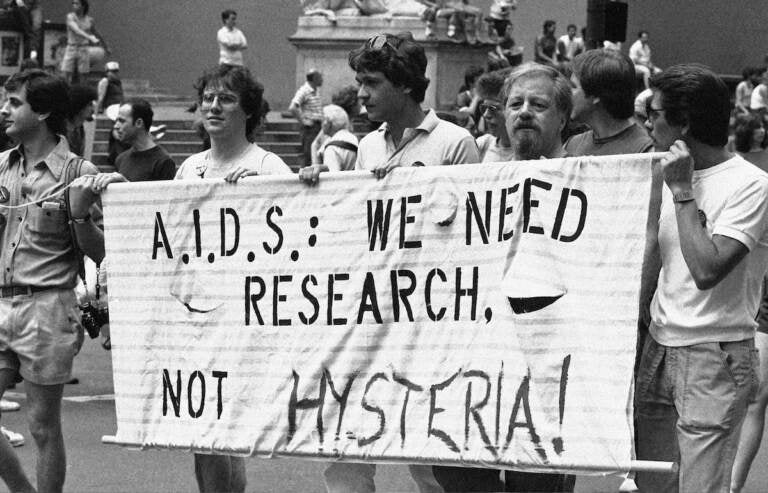

A group advocating AIDS research marches down Fifth Avenue during the 14th annual Lesbian and Gay Pride parade in New York, June 26, 1983. This year’s parade is dedicated to victims of the incurable disease AIDS which primarily afflicts homosexual men. (AP Photo/Mario Suriani)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In the spring of 1982, epidemic intelligence officers were almost a year into a troubling investigation. Residents of three major American cities, mostly gay men, were dying young and no one knew why. A handful of researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were tasked with traveling the country to interview patients and spot patterns.

Maybe bad drugs were to blame? Or it was something environmental?

“When reports come back that a number of cases that seem to have sexual contact with one another, they realized that this would offer support for a viral agent … the notion that whatever was causing it could be transmitted sexually, and that this could help with their investigations,” said Richard McKay, historian and author of “Patient Zero and The Making of the AIDS Crisis.”

Interviews in Los Angeles revealed a number of those dying had sexual contact with one another.

“This was the formation of the so-called cluster,” McKay said.

The revelation convinced the CDC to invest more resources into this type of cluster research – the painstaking process of linking one case to the next in the hopes it could lead researchers back to “the source”: whatever unknown viral agent was at the center of this growing, miserable web.

Before long a number of cases were connected by sexual contact with one person specifically: a Canadian flight attendant. The CDC already knew this man as “Case 57.” He was one of the few cases researchers had previously observed outside of New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

Researchers tracked down “Case 57” again and asked him about his sexual partners. The flight attendant was cooperative and opened his personal address book and shared all the information he has on who he’s been with during his travels: over 70 names.

It wasn’t nearly a complete list, but it was a start. One that allowed investigators to keep connecting the dots in pursuit of what was causing these deaths.

“The CDC’s cluster study was mostly finished by the autumn of 1982,” McKay said.

The study was reviewed internally at the CDC and prepared for publication for over a year. During this process, changes in terminology were made. Subjects were no longer referred to as “cases,” instead they became “patients.” One version of the report, annotated by hand, assigned a number to each patient depending on which of the three major cities they were from.

But the flight attendant, “Case 57,” was not from any of those cities. He could not receive a corresponding number label. Instead, he was given a letter: “O,” short for “Out-of-California.” Researchers faced another problem when typing up the report: The placeless patient “O” did not fit neatly within any of the studied city clusters illustrated in the study’s diagram. So eventually the decision was made to place him in the center of the diagram.

“It was finally published in March of 1984,” McKay said. And then, he said, something weird started to happen.

Subscribe to The Pulse

While the researchers who wrote the report continued to refer to the flight attendant as patient “O,” others, including some within the CDC, started to call him something different.

“Patient ‘O’ became patient zero it seems through a combination of understandable reading errors, and possibly also the similarity of “O” and zero on the typewriters used at the CDC,” McKay said.

Zero. As if the flight attendant himself was “the source” — the starting point or the center of a web.

This was how the phrase “patient zero” was born. And now, the term is ubiquitous. The phrase has come to represent an individual who starts something – be it a trend or a plague.

Mckay reveals more about this origin in his book, including the life and death of the original “patient zero,” Gaëtan Dugas, the flight attendant at the center of the CDC’s cluster study. Dugas’ name and identity first became known to the world thanks to “And the Band Played On,” an international bestseller by journalist Randy Shilts published in 1987.

Often regarded as the definitive history of the early days of the AIDS epidemic, Shilts’ work leaned heavily into the CDC’s cluster study and the idea that Dugas had a central role in the epidemic’s origin. It was eventually adapted as a TV movie for HBO.

But Mckay argues the book relied on a centuries-old instinct to identify someone to blame for a novel illness before having all the facts — or despite them altogether.

“In the story that Shilts wrote, where he identified Gaëtan Dugas by name, he combined a number of different elements from the older historical impetus to find an early case that had existed separately, but he brought them together in a really dramatic form.” McKay said.

Shilts portrayed the flight attendant as a devilishly handsome, recklessly sexual superspreader. The labeling fluke at the CDC provided an all too pithy, almost metaphysical confirmation that Dugas was singularly to blame for AIDS.

But this story was far from the truth. Due to the incubation period of HIV, it is highly unlikely Dugas gave HIV to all those he was connected to in the cluster study. Mckay said the scientific community was aware of this by the time Shilts’ book was released in 1987.

What’s more, the same month “And the Band Played On” was published, new information had surfaced that should have slowed down this “patient zero” narrative surrounding Dugas.

In media reports, researchers alleged that tissue samples that had been taken from a St. Louis teenager almost two decades earlier had been re-analyzed and tested positive for HIV. The samples came from Robert Rayford, an African American boy who died in 1969.

Rayford had come down with a mysterious combination of symptoms – so mysterious that his doctors stowed away tissue samples for further study. With these new test results in hand, researchers claimed this was a classic case of AIDS.

Writer and AIDS organizer Ted Kerr has been researching the life and death of Robert Rayford for years. In 2016, he spent a summer in Rayford’s hometown where he tried to trace this history.

“I really thought that I would go to St. Louis, and there would just be a wealth of knowledge about Robert Rayford waiting for me,” Kerr said. He hoped to find some sort of museum exhibit, archives, or a plaque. “But in fact, the opposite was true.”

Kerr said he didn’t find one person who had even heard of Rayford. So he started asking around. Although Rayford was a remarkably private person, Ted eventually collected information about where the boy lived and where he was buried. He found his death certificate and searched school records and yearbooks for clues about Rayford’s life.

He was obsessed — like another disease detective on the trail of HIV. But he couldn’t shake some advice he received from a friend when he first started looking into Robert Rayford.

“During that first summer of research, I was posting things on Instagram, as I was discovering things like the, like the 1987 headline that confirmed Robert’s death,” said Kerr. “And I had a friend who is an AIDS activist in Canada, just message me privately and say, ‘Be careful, don’t turn Robert into the new patient zero.’”

Kerr knew the label could spell trouble even if the person was no longer around to hear it.

Although flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas died before anyone knew him as patient zero, Richard Mckay said the publication of “And the Band Played On” brought on a tsunami of suffering for Dugas’ family.

“Shilts and his publisher did not contact Dugas family before the book came out. And so they were very much hit with a wave of negative publicity and huge amounts of media interest requests for interviews,” Mckay said.

A slew of international headlines followed the book’s publication — dubbing Dugas a “monster,” “the Columbus of AIDS,” placing responsibility for the entire epidemic on “The Man Who Flew Too Much.”

Journalists suggested Dugas refused medical attention and opted to have sex with as many people as possible. His widowed mother and siblings, all exhausted, pleaded for an end to the “web of untruths.”

“[They received] huge stigmatization for being the family members of the man blamed for introducing the most deadly new epidemic in North America in decades,” Mckay said.

Claims of Robert Rayford’s HIV positive tissue samples taken from well over a decade prior did little to slow the anger aimed at Dugas, but in smaller circles, a new round of speculation was sparked.

“There’s ways in which people try to claim Robert as gay or maybe try to connect him to conspiracy theories that were happening around lead poisoning in St. Louis, or underground child prostitution rings in St. Louis. And I think all of those are not helpful. They’re understandable, but they’re not helpful,” Kerr said.

According to Kerr, many in the medical community don’t even include Rayford in the history of HIV because of the way his story unfolded. Somehow, the press reported on Rayford’s HIV diagnosis before the results appeared in a peer-reviewed publication, which has led some to question the veracity of those tests.

Moreover, the results have never been replicated and likely never will be.

“The saved tissues were destroyed during Hurricane Katrina. So no more scientific investigation can be done on the material that came from Robert’s body,” Kerr said.

At this point, researchers aren’t sure exactly when HIV entered the United States or how it got here. New research suggests the virus may have originated in Africa before spreading to islands in the Carribean and eventually entering New York City as early as 1970.

Still, Ted remains interested in the life of Robert Rayford and what his death may reveal —– not so much about the boy, but about all of us.

“If he had been a white person or somebody older, would the alarm bells that had that that began the AIDS crisis response in America…would they have rang in 1969 when he died if he had not been a black teenager?” said Kerr. “So I think the medical community also doesn’t want to wrestle with those questions.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.