Head of NASA mission hopes it proves Pluto is a planet

Listen

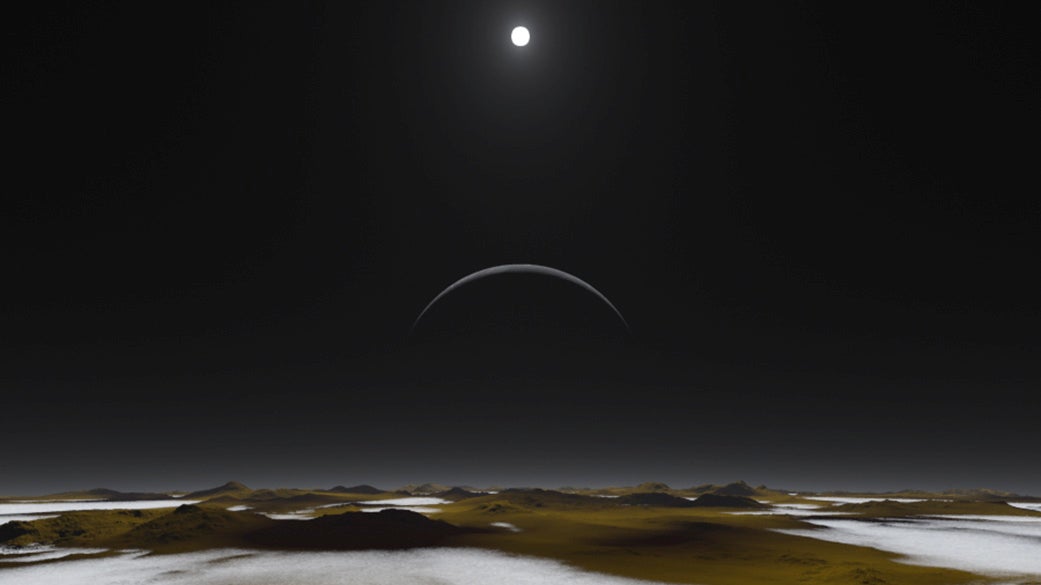

This illustration depicts daytime on the surface of Pluto with the sun high in the sky and Pluto's moon

A spacecraft traveling 31,000 miles an hour, will fly over Pluto and its five moons on July 14, giving us our first ever close-up view of the icy, dwarf planet.

The spacecraft New Horizons has been hurtling toward the edge of our solar system for the past nine years. Traveling 31,000 miles an hour, it will fly over Pluto and its five moons on July 14, giving humans our first ever close-up view of the icy, dwarf planet.

The head of the mission hopes the images beamed back to Earth will end a nearly decade-long debate and result in Pluto being reinstated as our solar system’s ninth planet.

‘Planet’ first defined in 2006

When New Horizons launched in January of 2006, rocketing toward a ruddy-colored planet frozen to about 400 degrees below zero, it was dubbed the “first mission to the last planet.”

That was a title California Institute of Technology planetary astronomer Mike Brown knew wouldn’t last.

“It was obvious to me that something was going to happen,” Brown said.

The year before, Brown’s research team at the Palomar Observatory had discovered Eris, a large, icy body that orbits near Pluto.

“Either Eris, which is more massive than Pluto, was going to be added into the planets, which I have to say didn’t actually make much sense, or Pluto was going to be not a planet,” Brown said.

Prompted by the discoveries of Eris and similar bodies, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially defined the word “planet” for the first time just months after New Horizons launched, in August of 2006. The result: Pluto was kicked out of the exclusive club.

According to the definition, a planet must have enough gravitational force to either suck in all other matter surrounding it, adding it to its own mass, or slingshot it out into a different orbit. Astronomers call this “clearing the neighborhood.”

“What it means is that the region where the object orbits would be devoid of anything except itself,” said Alan Stern, principal investigator of the New Horizons mission.

Tiny Pluto, smaller than the Earth’s moon, has thousands of comparatively large neighbors in its neighborhood, the Kuiper belt, so it was demoted to “dwarf planet” status after the definition was adopted.

Pluto’s status still contentious

But Stern and many other planetary scientists never bought the astronomer’s definition.

“I don’t know a single expert, a single planetary scientist, that thinks that the astronomers made a good definition,” Stern said. “So we pretty much ignore it.”

Stern and others say the classification is unclear, as the definition never defines a planet’s “neighborhood,” and it purposefully seeks to limit the number of planets in the solar system.

What’s more, Stern said, even Earth would be unable to clear its neighborhood if its orbit were as large and slow as Pluto’s.

“The proper definition for a planet’s very simple,” Stern said. “It’s an object in space that’s large enough for gravity to make it round. We recognize big, round objects, rounded by gravity, as planets. It’s about that simple.”

Stern believes once we see images of Pluto hanging large and round in the cosmos, the public will once again start thinking of it as the ninth planet.

“I think you’ll want to refer to it in your mind as a planet, I don’t think you’ll know what else to call it,” Stern said. “There isn’t a better word for it.”

Mike Brown, who has made a name for himself professionally as the “Pluto killer” and agrees with the IAU definition of a planet, heartily disagrees.

“Maybe there will be a sign on Pluto that says, ‘Yes, I am a planet,’ or if we realize that for decades we’ve been wrong and it’s actually 20 times bigger than we thought it was, that would change our minds,” Brown said.

“Barring those two things, which seem unlikely, I don’t think there’s anything New Horizons could possibly find that would change our opinions about whether Pluto should be a planet.”

New Horizons to give us insight into beginnings of universe

There are results from New Horizons that Brown is excited to see, including scars on the surface of Pluto’s largest moon Charon. These scars will provide a record of the countless comet-like objects that have hit the moon over more than four billion years.

“The numbers of these, the history of when they hit is a history of how the solar system formed itself together and how it’s been sort of trying to shatter itself back apart since that happened,” Brown said.

Scientists have already learned something about these fragments in space from impact scars from asteroids and Earth’s moon, but the outer part of the solar system is a little more pristine, Brown said.

“It’s been in deep freeze for four and a half billion years, and so we can get a much cleaner record of really what happened at the very beginning.”

The mission itself is also historic: Stern said New Horizons is the end of a solar-system wide survey that started under President Kennedy.

“This is something that hasn’t happened in over 25 years, turning a point of light into a planet that humans know and understand,” Stern said. “Nothing like it is planned to ever happen again.

In the end, Pluto will be Pluto no matter what we call it after humans clap eyes on it for the first time.

What will change is how humans understand the most remote reaches of our solar system.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.