Decades after Columbine, preventing school shootings still vexes security experts

A 1958 deadly fire at a Chicago school was the catalyst for life-saving fire drills. Experts say the 1999 Columbine shooting spurred school security changes at a slower pace.

Listen 4:48

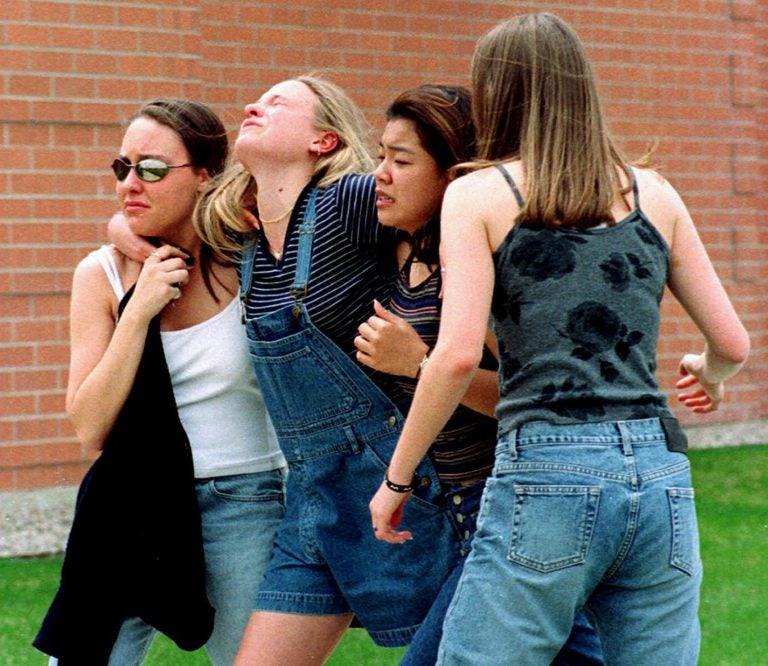

On April 20, 1999, unidentified young women head to a library near Columbine High School where students and faculty members were evacuated after two gunmen went on a shooting rampage in the school in the southwest Denver suburb of Littleton, Colorado.. Fifteen people, including the two shooters, died. (Kevin Higley/AP Photo)

Before Columbine and Newtown and Parkland, there was Our Lady of Angels.

On Dec. 1, 1958, a fire broke out at the parochial school on Chicago’s West Side, killing 92 students and three nuns. The Our Lady of Angels catastrophe shocked the country and spurred action, leading to the proliferation of fire drills, sprinklers, and other protocols that have so far helped prevent another similar event from occurring in America.

Nearly two decades after the infamous massacre at Columbine High School in Colorado, why haven’t ghastly school shootings gone the way of ghastly school fires?

For Aaron Vanatta and other school safety experts, it’s a vexing question.

“You thought you’d see a lot more change a lot quicker,” said Vanatta, a school police officer in the Quaker Valley School District outside Pittsburgh and a regional director for the National Association of School Resource Officers. “But it didn’t really happen that way.”

That doesn’t mean there haven’t been changes since Columbine.

The protocol for confronting school shooters has just about reversed itself over 19 years.

At the time of Columbine, Vanatta said, cops were told to establish a perimeter and wait for a trained SWAT team to arrive. Now, police departments train officers to engage the shooter immediately, Vanatta said, because research shows many mass shooters surrender or commit suicide as soon as police arrive.

There’s also been a sea change in how staff and students are taught to respond. Early wisdom told students to shelter in place, turn off lights, and lock doors. Nowadays, officials preach an “options-based” response where students flee if they can, hide if it’s practical, or fight back when they must.

“If the the bad guy’s at the north end of the building, and occupants are at the south end of the building, why would those people at the south end of the building wait there?” Vanatta said.

Laws have changed, too, said Jennifer Thomsen, director of the Knowledge and Research Center at the Education Commission of the States, a nonpartisan group that tracks school policies.

She places the legal shifts into two main phases.

After Columbine — an event perpetrated by two teenagers who attended the school — new state laws tended to focus on how schools deal with aberrant student behavior.

“So, for example, strengthening codes of conduct and modifying laws regarding suspension and expulsion of disruptive or threatening students,” Thomsen said.

Take Delaware, which in 2000 passed a law requiring schools to notify parents about state rules regarding bomb threats, destruction of property, disrupting school, and reporting crimes.

The second swell of laws arrived 13 year later, after a man killed 20 first-graders at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. Since the crime wasn’t perpetrated by a student, the respondent laws looked more at guns in schools and emergency preparedness, said Thomson.

In Delaware, the state legislature passed a law requiring each school to conduct two lockdown or intruder drills each year. New Jersey lawmakers established a “School Security Task Force” to “develop recommendations to improve school security and safety.”

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania created a grant program to fund district-level school-safety projects.

Easier to prepare for a fire than a shooter

The Pennsbury School District in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, has used state grants for an anti-bullying program and walkie-talkies to improve emergency communication. Abington School District in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, has hired school-based officers and purchased “go kits” that can be used in emergency situations.

Districts across the country have invested in all sorts of new safety infrastructure. Surveillance cameras, metal detectors, and card-scan systems are just some of the physical augmentations that have proliferated in the post-Columbine era.

Pennsbury, for instance, has equipped its schools with secure lobbies that allow school staff to screen all visitors before they enter.

“Those things did not exist in all of our buildings 20 years ago,” said Elizabeth Aldridge, Pennsbury’s director of pupil services.

For Aldridge, however, the change that stands out most is the increasing number of safety drills. Pennsbury now requires intruder drills every quarter, and that includes kindergarten classes.

But whereas fire drills — combined with other reforms — have helped snuff out the specter of major school infernos, school shootings persist. This despite the fact that schools have “hardened” their targets with new technology, raised awareness through training and drills, and changed the way they intercept troubled students.

Part of the problem is circumstantial, said Amanda Klinger with the nonprofit Educator’s School Safety Network. An attack from a gun-wielding human is simply harder to prepare for than a fire.

But she also believes the response to Columbine and Sandy Hook has been less coordinated than the response to the Our Lady of Angels fire in Chicago. As an example, she points to all the different types of drills schools do — intruder drills, active-shooter drills — many with their own distinct variations.

“How can we come to some sort of consistency so that everybody is increasing their level of preparedness?” she said.

Many also cite the nation’s gun laws and gun culture as causes of the continuing problem.

President Donald Trump has proposed allowing districts to arm teachers, theoretically further fortifying schools against potential assailants. A group of academics who study school violence recently released a list of suggestions that includes restricting gun access and increasing mental health services.

And as most have already heard, students across the country are walking out of school Wednesday to call for more gun control. The rallies are another reminder that, while school safety looks different than it did 20 years ago, it confronts many of the same challenges.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.