Cutting salt in Chinese takeout to curb heart disease

With poverty and stress driving up high blood pressure in communities of color, will it help to cut sodium in Chinese food? Health officials say it’s a worthy effort.

Listen 8:57

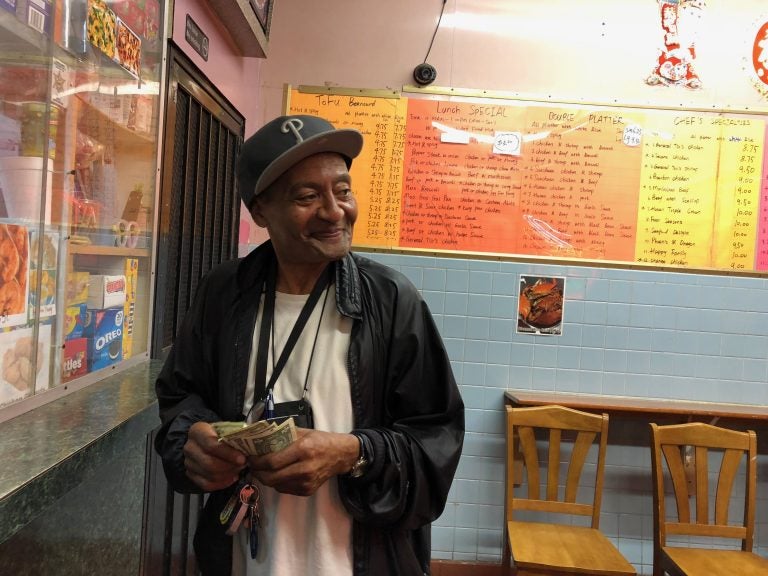

George Walker works in West Philadelphia and eats regularly at a range of Chinese takeout places in the neighborhood. (Nina Feldman/WHYY)

Philadelphia has a sodium problem. Almost 40 percent of all adults, and over half of African American adults have high blood pressure. To tackle this issue, public health officials are working with Chinese takeout restaurants across the city to cut salt in some popular, high-sodium dishes.

It’s a convincing argument: Chinese food is high in sodium, many of these takeout restaurants are in predominantly black and Latino neighborhoods. From a public health perspective the strategy checks out. But the approach has skeptics.

Walking down Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia, a hungry dinner-seeker has her choice of tasty, affordable Chinese takeout food. There are over than 400 Chinese takeout places in Philadelphia — according to the city’s public health department, that’s more than the number of most popular fast food chains combined: Burger King, Wendy’s, McDonald’s, Pizza Hut and KFCs.

When I met George Walker, he was contemplating the menu at Choy Wong, a simple takeout place with a few chairs lined against the wall for customers to wait for food. Candy bars line the ordering counter, and the menus are written by hand on bright, neon poster board. Walker works nearby and knows what’s good in the neighborhood.

After some deliberation, and consulting with the chef behind the counter, he decided to head down the street to a different takeout spot — there’s plenty of competition for his business.

“They have smaller portions of egg-foo young” Walker said. “They really know how to cook down there.”

This multitude of Chinese takeout options in the neighborhood was exactly what former Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter and other city officials noted a few years ago when he had the idea for a lower-sodium initiative.

“They noticed these like yellow signs all down the street and Mayor Nutter was like, ‘what are those signs for?’” recalls nutritionist Jennifer Aquilante, a food policy coordinator with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

“And they looked closer and realized they were take out restaurants. And he was like, ‘Wow, there are so many Chinese takeout restaurants around. We should do something with those.’”

The city worked with owners to use less soy sauce and fewer other high sodium seasonings in the three most popular dishes: chicken lo mein, shrimp and broccoli and General Tso chicken.

Restaurant owners received training from a professional chef on ways to alter their recipes while still maintaining flavor. Aquilante says in this context, even just a little sodium reduction goes a long way.

“I think like 600 – 900 mg you can see a reduction in your blood pressure points,” she said.

There was no financial incentive for restaurant owners to participate, and the program was completely voluntary. Still, more than 200, or about half of all takeout restaurants signed up. Researchers at Temple University’s Center for Asian Health studied the effort. They found that a year and a half after the restaurant owners changed their recipes, they were still making the dishes with an average of about 25 percent less sodium.

The study didn’t measure actual health benefits for the customers, so there’s no way to know if sodium intake actually went down. Diners could have just ordered different dishes, added salt, or ate at different restaurants. But, the city conducted taste tests, and Aquilante said customers couldn’t tell the difference between the dishes before and after sodium was reduced.

Ling Lin runs a takeout place in North Philly, a predominantly African American neighborhood. Her restaurant is working with the city — she said her customers did notice when they changed the recipe — and that made her nervous.

“First of all we worried about it, [that] we would be losing the customers,” Lin remembers.

But she said, once she started talking to people about why they changed the recipes, diners got on board.

“When we explain to the customers, they understand we helping them,” Lin said.

But why a program designed just for Chinese takeout places? Why not also work with pizza parlors and cheesesteak places? When asked about this, Lin said, she didn’t feel singled out — her customers value healthy food, so if the city can help her make her dishes healthier, great.

But food and science historian Sarah Tracy is wary.

“Anytime you do that — you start with an ethnic group first, in the name of a health initiative, you’re helping to shore up those boundaries of racial or ethnic difference,” said Tracy, who worries an effort like this one bears a striking resemblance to another time where Chinese restaurants were targeted for a certain ingredient.

Tracy is writing a book about the history of MSG, or Monosodium glutamate, a chemical compound used in lots of Chinese food. It’s in plenty of other foods too — like Doritos, Campbell’s soup, and KFC. It adds that savory, umami quality that keeps you going back for more.

In the late 1960s, MSG came under fire in the medical world after a Chinese American doctor wrote to the New England Journal of Medicine. In his letter, the doctor described symptoms he was experiencing after eating at certain Chinese American restaurants — numbness, tingling, flushing in his neck and head — and inquired as to whether or not his fellow physicians were encountering patients who’d had similar symptoms.

From there, says Tracy, a sort of panic cropped up about MSG in Chinese food, and the symptoms the doctor described became known as Chinese Restaurant Syndrome. Restaurants were quick to boast they cooked without it because they didn’t want to lose customers.

Later, in the 1990s, the Food and Drug Administration commissioned a study to look at MSG’s adverse health effects. It turned out, there weren’t many. For a very small subset of people, MSG can cause a bad reaction. But for most, it’s safe. Tracy said she doesn’t think the hysteria was really about the food.

“It was also about fears around migrant populations and what kind of America are we living in? Who is American, how do immigrants influence what kind of America we want to create in the future?”

This MSG “scare” came just after the Immigration Act of 1965 made it easier for of Chinese and other Asian immigrants to come to the United States. Tracy says intolerance for these new groups stoked fears around MSG. Now, even after the FDA has shown that MSG is usually not harmful, Tracy says the damage has been done. Chinese food — and, Chinese culture — is still often linked with an additive perceived to be toxic.

As I’m waiting for my order at Chow Wong West Philadelphia, the city’s Chinese takeout initiative is on my mind. What are the potential risks of framing a public health effort around a specific group? As it was with MSG, could it create a stigma to single out ingredients prominent in the food of one ethnic group? Why do it that way, if you could do it another way?

And there’s another layer here — what would be most helpful for the people eating the food? In this case, the Chinese takeout initiative is focused on improving the health of black and Latino Philadelphians. African Americans do have higher rates of hypertension than their white counterparts — but there are a million other things that could be contributing to that disparity

“It’s much easier to lecture people about what they’re supposed to eat than it is to change conditions of structural inequality,” said Tracy.

Tracy is talking about the other factors in people’s lives that can cause high blood pressure, up your risk for heart attacks or stroke.

For one — chronic stress is linked to those health risks. Living in poverty, which a quarter of Philadelphians do, is a huge stressor. Violence is another big one.

More and more public health experts are looking beyond people’s individual choices — and pointing to community level forces like these that affect health.

Experts are looking at the factors contributing to which food options are available in any given neighborhood. Do low-income, black and Latino residents have the same political power to lobby for other, healthy affordable food options in their neighborhood?

If the answer is ‘no’— that might help explain the take-out signs lining the avenues in West Philly.

But – food historian Sarah Tracy acknowledges those are complicated problems to untangle.

“It’s easier to say, oh you need to take some sodium out of your chinese restaurant takeout,” she said.

Philadelphia public health officials say part of why they like the lower-sodium program so much is that they have a great relationship with the local Chinese Restaurant Association, which is well organized and easy to work with. Often for public health initiatives, buy-in from the community is key.

And, the takeout initiative is just one strategy. Philadelphia also recently passed legislation that will make it mandatory to put warning labels on menu items with high sodium.

The public health department is sticking with the Chinese restaurant approach — next, they’re launching a project focused on Chinese buffets.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.