CHOP researchers: Why are so many young teens getting kidney stones?

Over two decades, there's been a sharp increase among adolescents with the disease. Historically, the condition affected mostly middle-aged white men.

Listen 5:28

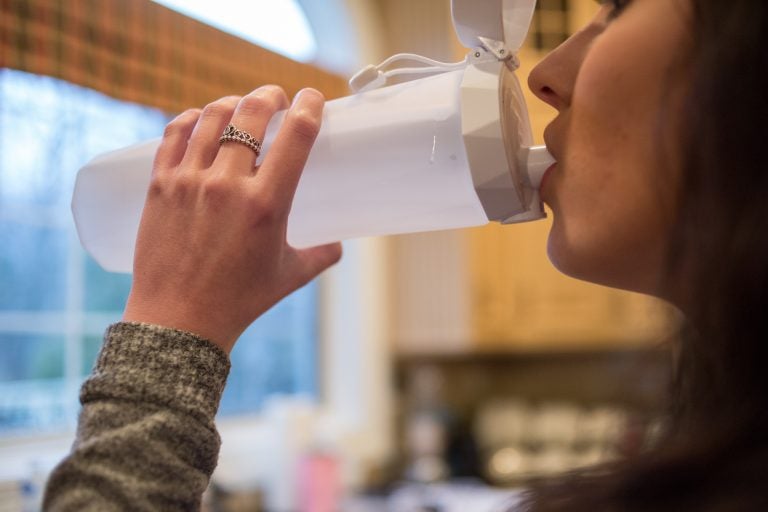

This teenager is part of a medical study at CHOP to see if drinking a certain amount of water per day can help decrease a certain type of kidney stones. The special water bottle has a "wand" inside which tracks the ounces of water consumed and sends the information to an app on the teen's phone. (Emily Cohen for WHYY)

When Elizabeth was 9, she started getting terrible back pain. She felt sick, her side ached, and she would take to her bed for days. For a while, she and her parents assumed the cause was one of her many food allergies.

Four years later, they realized it was something else: kidney stones.

Her mother almost didn’t believe the diagnosis.

“She’s too young. That was my original thought,” her mother said. “And she has a great diet because she doesn’t eat soy, gluten or dairy. She basically has the Mediterranean diet.”

By then, Elizabeth had only 10 percent function in her left kidney and about 85 to 90 percent in her right. She ended up needing surgery, but even a year and a half later, she still gets stones.

“I have sharp pains all day, and then it hits you at one point, and it’s like a rock falling on your side, and you’re just like bedridden for three days,” Elizabeth said.

In many ways, Elizabeth is the quintessential young patient with kidney stones: 15 and female. In adults, where the disease predominates, the condition still affects more men than women; in adolescents, slightly more girls get stones than boys.

Elizabeth isn’t her real name. We’re shielding her identity because she is a part of the PUSH study — short for prevention of urinary stones with hydration — through the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia that hopes to prevent young patients from getting kidney stones again.

Gregory Tasian, an attending pediatric urologist at CHOP, is leading the PUSH study there. He is concerned by the growing number of teens getting kidney stones, both in his practice and nationally. At this point, there aren’t good population-level numbers for how many adolescents are affected by the condition, but small, regional studies have shown a significant increase over two decades. In particular, Tasian worries about an increasing number of kidney stones in African-Americans, among whom the rate is rising at about 5 percent per year.

“When you’re talking about an epidemic, this is something in epidemic proportions,” he said. “How quickly this has changed over such a short period of time is really dramatic.”

Better detection, dietary changes

Doctors are still trying to figure out why the rate among teens is surging. Many blame changes to our diet, especially an increase in salt, phosphates, and protein. Technology has also made it easier to pick up very small stones using CT scans and ultrasound.

Alicia Neu, chief of pediatric nephrology at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, said improved imaging has allowed doctors to detect the condition earlier.

“Ten, 20, 30 years ago, if that child presented with mild abdominal pain or back pain and maybe a little bit of blood in the urine, we might not have seen the stone and diagnosed them either with viral gastroenteritis or constipation,” she said.

Nevertheless, the substantial growth in patients led Johns Hopkins to establish a pediatric stone program about a decade ago, and patient volume has continued to increase.

Doctors are seeing similar growth across the country, and specialized pediatric kidney centers are sprouting up to meet demand. CHOP has had a Pediatric Kidney Stone Center since 2014. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles established a comprehensive stone program two years ago to deal with the sharp increase in the number of young patients with kidney stones.

“We’ve had basically a triple in the number of stone cases that we do over the past two years,” said Scott Sparks, assistant professor of clinical urology who directs the program.

Sparks said, in his experience, children make stones for many of the same reasons adults do: poor diet and poor hydration. But he suspects that diet alone doesn’t explain the growing problem in teens.

“Our diet has probably not changed substantially in the past two to three years such that it would account for such a significant increase in the number of patients that we’re seeing,” he said.

As many researchers are these days, CHOP’s Tasian and his colleagues are looking at the microbiome — all the microorganisms that live in a certain area of the body. Tasian is interested in the impact of antibiotics on the bacteria in the gut and urinary tract of people with kidney stone disease.

“If we can understand what some of these differences are in the community of organisms, then I think we’re going to be able to better understand what is going on with metabolism that is causing these stones to form,” he said.

Prescribing water

One factor all doctors seem to agree on is that today’s teens aren’t drinking enough. Kidney stones are made up of minerals from our diet. Our body uses what it needs and the rest goes out in our urine. To form crystals that turn into stones, those minerals need to find each other. The less we drink, the less urine we produce, and the more likely those things are to find each other.

Neu, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, uses the analogy of making a beverage from a powdered mix.

“If you don’t add enough water, that drink mix isn’t going to dissolve, no matter how much you stir it,” she said. “The only way to get it to dissolve is to add more water.”

That brings us back to the study Elizabeth is enrolled in at CHOP. The two-year, NIH-funded study uses a combination of technology, incentives, and coaching to get patients to drink more. The idea is to prevent people like Elizabeth from getting stones again. Once a teen like her has had a stone, there is a 50 percent chance he or she will get another within three years. The study, including adolescents and adults, is the first and largest of its kind.

Each patient gets a “smart water bottle” that connects to a phone app. The bottle is sort of like a FitBit for water, with a small tassel and a sensor stick that lights up either to remind patients to drink or to celebrate when they’ve met their daily goal.

The app collects real-time information on liquid intake and sends that information to study leaders. For the first six months of the study, Elizabeth gets $1.50 every time she meets her daily goal; for the seventh through 18th month, the amount she gets will peter out. There are also “fluid coaches” who help patients find ways to drink more.

So far, drinking more has helped Elizabeth. She still passes stones, but not as often, and they aren’t as painful. She’s trying to maintain a sense of humor while the science catches up with her condition.

“I always joke with myself that I’m aging like a dog,” she said. “Like I’m getting all these medical issues when I’m such a young kid at 15 years old.”

Doctors say they hope more research into the causes and treatment of stones in adolescents will prevent this and other traditionally “adult” conditions from developing earlier in life. The PUSH study, which also involves the University of Washington-Seattle, University of Texas Southwestern, and Washington University in St. Louis, will enroll participants for the next year and a half, and results should be available in about four years.

—

Correction: In a previous version of this story, the name of the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center was misidentified.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.