After student suicides, medical schools look for changes

Listen

Talyah Basit attends the suicide-prevention conference at the War Memorial in Trenton. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Following the death of her son, Michele Dietl remembers not being able to walk through the grocery store.

“I couldn’t do it. Because I would see his favorite foods and I would cry,” Dietl said, sitting at her kitchen table in the suburbs of St. Louis, Mo.

Looking at family photos, her son, Kevin, is hanging out on the beach, or playing the upright bass with his younger sister. His father, John Dietl, remembers how Kevin would train for marathons on a treadmill in the basement.

“He was very resourceful. There was a point in time in his first two years he was having difficulty with the testing. And so he sliced open all his books—I still have them downstairs—and he fed them through a scanner and had his computer read ‘em back to him,” John said, snapping his fingers. “That did it.”

Kevin, a fourth year medical student, attended A.T. Still University in Kirksville. He took his own life in the spring of 2015, just weeks before graduation. He was 26.

Kevin’s parents said their son recognized he was becoming depressed during his time in medical school, but thought that getting therapy would come up when he applied for jobs later. His parents pleaded with him to seek counseling, which he did… out of town, under a fake name. Paying cash.

“We didn’t know what we were looking at,” his father said, recalling a conversation he had with one of Kevin’s close friends after his death.

“He told us that he had talked to Kevin in the third year, and he said, ‘Kevin, I think you’re having a mania.’ And he said, ‘You know why I didn’t say anything? 20 to 30 percent of kids in our class were doing the same thing.’”

Three to four hundred physicians die by suicide in the U.S. each year, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Medical schools aren’t required to report suicides among their students, so it’s hard to know how often this happens.

But on the campus of St. Louis University’s School of Medicine, not too far away from where Dietl grew up, people are trying to see if there’s a better way to do this.

Eight years ago, administrators measured the rates of depression and anxiety among their students for the first time. More than a quarter of students reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression after their first year of med school. Fifty-seven percent reported symptoms of anxiety.

“I felt like I’d been kicked in the stomach,” said Dr. Stuart Slavin, the school’s associate dean of curriculum. He had assumed the students were doing fine.

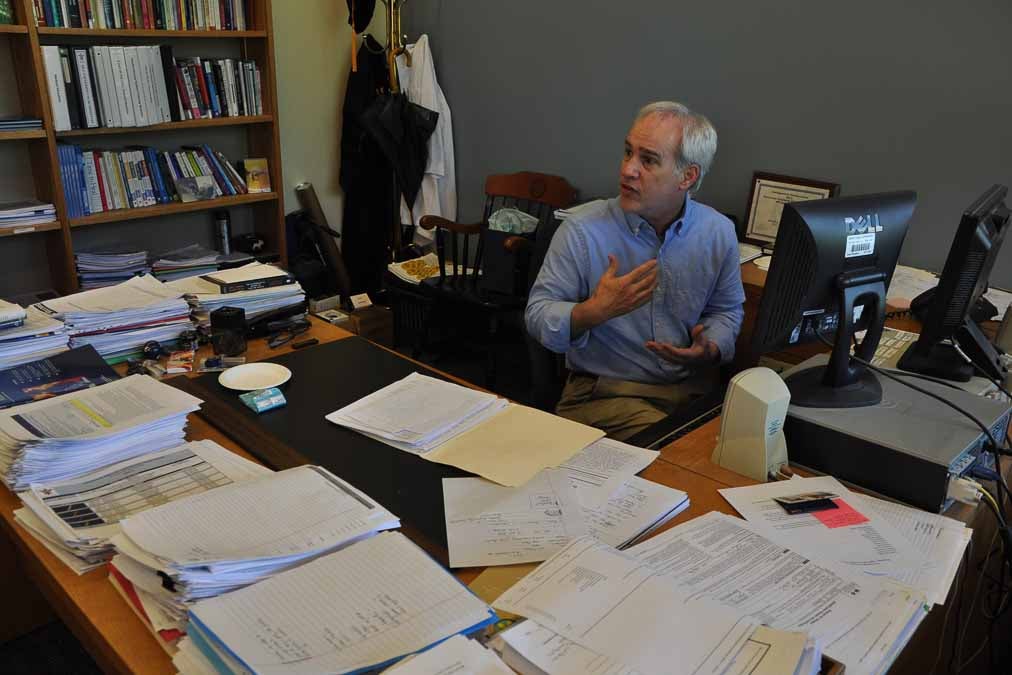

Dr. Stuart Slavin, associate dean for curriculum at Saint Louis University’s School of Medicine, in his office. (Durie Buscaren/for WHYY)

“And there was a sense of personal responsibility. We had evidence that when students started here, they looked like the general public. So, as associate dean for curriculum, it was like… we are doing this to them, right? And I am kind of responsible,” Slavin said.

What followed was a methodical overhaul of the school’s curriculum, with a focus on student well-being.

Slavin distributes mental health assessments to students every year as a kind of barometer for how they’re doing.

First, letter grades for first and second year classes were eliminated, so that students either pass or fail each one. The content covered in those classes was scaled down about 10 percent, meaning that students actually have free time.

In addition, every student takes a seminar in mental well-being and resilience, taught by Dr. Slavin. Anatomy—the course where first years dissect a human cadaver—is no longer the first class they ever take.

In the meantime, Slavin says, average scores on board exams have actually increased, from 222 to 229—although the national average has also gone up.

“People think that by backing off, oh, you know, our medical students aren’t going to be as well prepared, there’s evidence they’re actually better prepared, despite making life easier for them,” Slavin said.

To see how it works, head down to the medical school’s basement—where a crew of second year students started a jam band. They call themselves the Palpations… which they explain is a medical pun that stuck.

“We were doing anatomy, and during clinical anatomy you’re often told to palpate this and palpate that, and find those nerves and those veins and so forth,” jokes guitarist Tony Zunica.

Hyun Lee, who hopes to become a cardiothoracic surgeon, is the band’s drummer. He said that band practice is a welcome release; something he may not have had time for at a school that didn’t place such an emphasis on free time.

“You know, I come into med school with the mentality of, I’m going to study 24/7. For four years I’m going to pretend like my life is over and just do it. But that’s not possible. You just need a place where you can go and do something other than palpating people, I guess,” Lee laughed.

To Vincent Le, who also plays guitar, knowing how to balance classwork and the band is simply practice for life as a doctor.

“When I get out there, I want to be a doctor but I also want to have a life. I want to have a family. So making time for my hobbies and things I love, and not letting go of those, is really important to me,” Le said.

Members of “The Palpations,” a band started by second-year medical students. (Durie Buscaren/for WHYY)

Other students say they spend the extra time volunteering, hanging out with friends, or just doing basic things like going to the grocery store and getting their hair cut.

But maybe the biggest difference is that students say they’re encouraged to seek out help—like Katherine Hu, a third year student who grew up in California. During her first year in St. Louis, Hu says she struggled with anxiety, and the feeling that she didn’t measure up.

“Anything medical just bears that weight of I’m going to be helping someone and if I don’t know what I’m doing I could be hurting them, or I could be inadvertently causing harm to other people around me,” Hu said.

Hu started meeting with Dr. Slavin regularly, and keeping a journal—of three positive things that happened every day.

“It can be really anything from, I got to talk to my sister on the phone. Or I saw a really cool movie today,” Hu said. “It’s actually kind of nice, it’s like a condensed diary. So when you flip through the ones that you wrote before you can say oh yeah, I did really have a good week that week.”

After that first year, Hu says things are easier now. She’s not sure what specialty she wants to go into yet, but she’s excited for the future.

“If you take care of yourself, and establish these good habits early, you’ll be more successful as a physician and you’ll be more successful to take care of patients,” she said.

By St. Louis University’s most recent count, just four percent of students had symptoms of depression after their first year of classes. That’s about a fifth of where they were before the curriculum changes.

But these efforts aren’t always popular.

Dr. Stephen Ray Mitchell is the Dean for Medical Education at Georgetown University in Washington DC, one of the most competitive medical schools in the country. He says some professors scoffed at the idea of going to pass-fail classes.

“I was actually in favor of it, but people of my generation would say, oh wait you can’t do that. Because it will unfairly handicap the student when they’re competing for residencies,” Mitchell explained.

Then, a group of second year medical students started to lobby administrators, saying this really makes a difference—even though they wouldn’t personally benefit from the changes.

“They would sit down with the people who opposed them and say, help me understand what it is that you don’t like about it,” Mitchell said.

When the curriculum committee voted again, the decision was unanimous. Following St. Louis University’s cue, Georgetown has also started taking assessments of their students’ mental health.

A petition calling for the professional associations for American medical colleges and residency programs to track student and physician suicides, and to enact policies to prevent them, now has about 75,000 supporters… including Kevin Dietl’s parents.

They say efforts like this make them hopeful, that what happened to their son can be prevented for others. But there’s a long road ahead.

“There are others out there who could be going through this. And we want to make sure that they are aware, there are things you should look out for. And for people who have had this happen to them, they’re not alone, you know?” said John Dietl.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.