A Hitchhiker's Guide to Quitting

Julius BaDour lost his job, quit his relationship, and left his hometown to live a life on the road. He learned some lessons about quitting along the way.

Listen 11:35

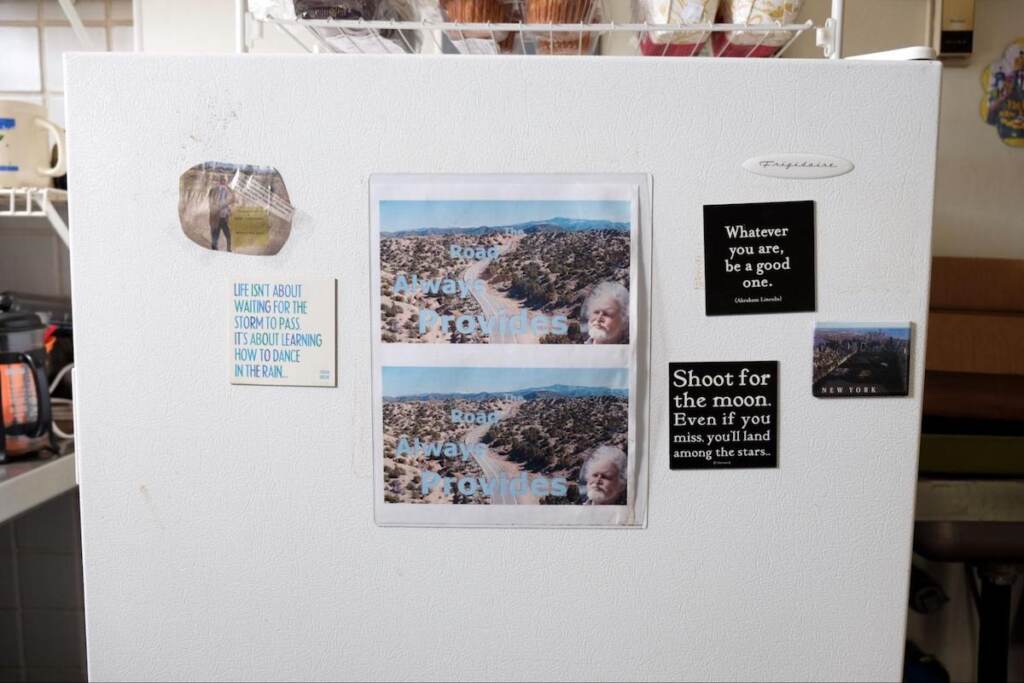

Julius BaDour at 19 years old in Santa Fe, New Mexico. (Alan Jinich/WHYY)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

I met Julius BaDour in Santa Fe, New Mexico in April of 2021. I was on a leave of absence from college, interviewing young adults across the U.S. about their lives during the pandemic. BaDour had just left his hometown of Madison, Wisconsin after losing his job and breaking up with his girlfriend.

His decision seemed to come out of nowhere, but it was really a breaking point after struggling for years with depressive thoughts and the trauma of his parents’ divorce.

“We moved a lot,” BaDour said. “I think I moved every year I was in middle school and high school. I was either sleeping in the same bed with [my dad], in my grandparents’ attic, or on the floor. I remember I couldn’t really go outside in that neighborhood. People were getting killed in front of the house.”

While the pandemic was at its peak, BaDour felt suicidal. But one day he came across a documentary series by David Chou on Vice called, How to Hitchhike Across America: Thumbs Up. It’s about these two grungy guys traveling cross-country with no money. After watching it, BaDour said he couldn’t think about anything else and decided to give it a shot.

“My life sucks. So, I don’t really care if something happens to me. I just wanna have fun,” BaDour said. “One of my biggest fears has always been like, I don’t wanna be old and look back on these years with regret.”

Before leaving, BaDour’s father told him that he couldn’t run away from himself. No matter how far away he tried to go, his problems would just follow. But nothing could stop him.

With only his backpack, guitar, and phone, BaDour traveled to Montana, Colorado, and then New Mexico. That’s where I met him by chance at a hostel in Santa Fe. He was the receptionist — and kind of resembled a young and disheveled Jack Kerouac. Turns out, “The Dharma Bums” is one of his favorite books.

A year on the road forced BaDour through life’s polarities in a whirlwind: depression and bliss, resilience and fragility. He hitchhiked thousands of miles, climbed mountains, and busked on the street with his guitar to earn some cash. He met other drifting travelers. Every day brought something new and unexpected — though not always positive.

“It is extremely romanticized,” BaDour said. “There’s a lot of bull**** that comes through with it. Sleeping outside — it’s not that fun. Sometimes it can be kind of cold.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

BaDour had worked the hostel job in Santa Fe for just a few months. And next he was headed to work with the Vermont Youth Conservation Corp. His life seemed like a cycle of discontinuity, quitting one thing for another, chasing the next adventure.

‘You can’t run away from yourself.’

Exactly two years after parting ways, I gave BaDour a call. To my surprise, he was back in Madison, his hometown. After hitchhiking cross-country and working different jobs in different states, he eventually ended up back in Santa Fe to live with a new girlfriend.

“We discovered we were both from Madison, from like, the same side of town,” BaDour said. “I was just head over heels for this girl.”

They moved back to Wisconsin together and BaDour started working in construction. He was so good at the job that his bosses chose him to lead his own construction site. But at the same time, his relationship was starting to crumble — and his girlfriend broke up with him.

“That’s when I really started to discover more about how my brain works. She was like my first love and I was really heartbroken. And I started drinking a lot,” BaDour said. “I was like everything just feels so much better when I’m drunk. So, that’s what I did. Because that doesn’t have any consequences, right?”

Buying alcohol was no problem for BaDour, even though he was only 20 years old.

“But I remember my turning point was being at work while having withdrawals, shaking,” he said. “I couldn’t hold my pencil still. And I was like, ‘man this sucks. I’m so sick of being hung up on this one girl.’ So, from that point on I didn’t drink any hard liquor.”

He got into therapy and came clean to his bosses. He told them he was going to quit drinking and it strengthened their trust. They even offered him to lead new construction projects in Minneapolis and Chicago. But BaDour had something else on his mind.

He quit his job again. This time, to hike the Pacific Crest Trail, which stretches more than 2,600 miles from the US-Mexico border up to Canada. The American West took up a new significance in his life as the place that he could return to time and time again to mature and to change his state of mind.

“If you wanna change something, getting new scenery is definitely a good place to start because it realizes that things do change even if it’s just the landscape. And it’s easier to make a change when you go somewhere new,” BaDour said.

BaDour hiked a big chunk of the Pacific Crest Trail and hitchhiked the Oregon coast. He even jumped on a freight train through Montana.

“I had the notion in my head that I’m never gonna come back to Wisconsin and I’m just gonna live out West,” he said. “But then after hiking that trail and really reflecting on myself, I was like, ‘you know what? I actually like Wisconsin and my family is there. I got a lot of support. I love my job there … I could very well see myself in Wisconsin forever.’”

He thought about sitting around the fire with his dad, smoking cigarettes.

“I didn’t realize how much I had missed him. The older I get and the more experiences I have, the more I realize I’m like both my parents.” BaDour said. I remember my dad telling me, ‘You can’t run away from yourself. Wherever you go, you’re gonna be there. So, you really need to face it head on.’”

When I asked BaDour what quitting means to him now he said, “Quitting isn’t just a negative thing … It can be life changing and make you a happier person overall. It’s showing that you have power over your own life. Like, I’m in control. And I’m quitting this because I can.”

You can see the full oral history project at Generation Pandemic.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.