9/11 rescue worker chooses to have her body preserved after death

9/11 rescue worker wants the world to see the toll the work took on her body.

Listen 10:52

Dr. Gunther von Hagens (right) and Dr. Angelina Whalley (left) working on a plastinate. (Gunther von Hagens’ BODY WORLDS, Institute for Plastination, Heidelberg, Germany)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

When Body Worlds debuted in the U.S. at the California Science Center in Los Angeles in 2005, physician Angelina Whalley, the exhibit’s co-founder, was anxiously waiting to see the public’s reactions.

“I vividly remember one incident of a young woman – she might have been in her 20s or early 30s – she started crying,” she said.

Overcome with emotion, the woman told Whalley that she tried ending her life three times, and previously felt like her life was “useless.”

“‘But now that I see how intricately and wonderful the human body is made,” she told Whalley. “I feel I have something very important, something very wonderful inside me. And I promise you I’ll never do that again.’”

For Whalley, this profound feeling of emotion is what she wanted Body Worlds to be – a journey under the skin touching aspects of life and death.

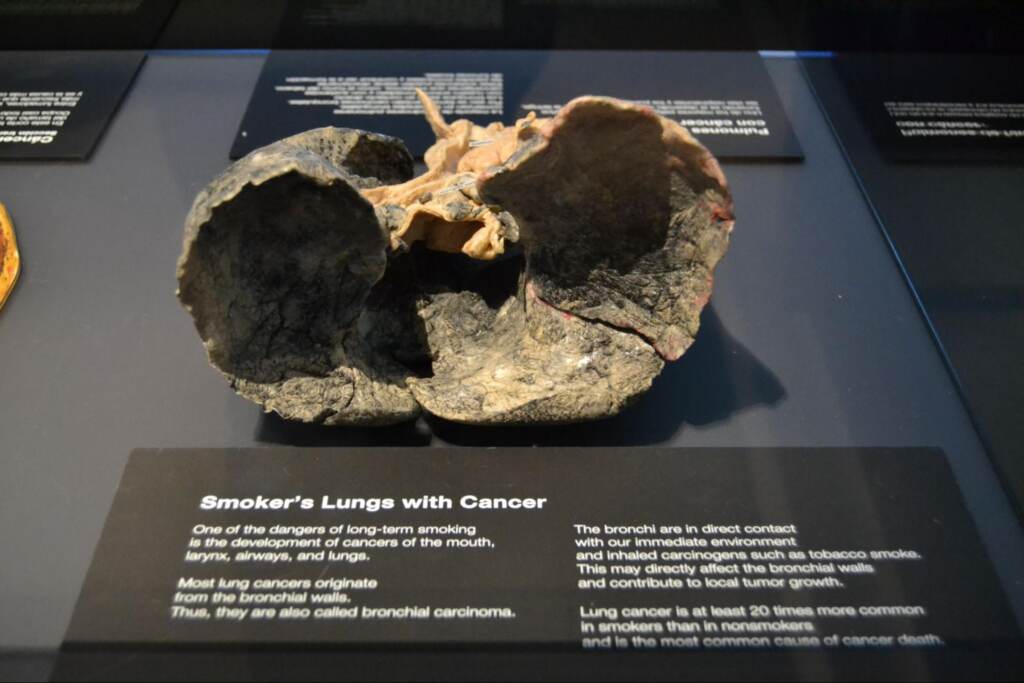

Body Worlds is aimed at teaching the effects of healthy and unhealthy lifestyles. It features the remains of human cadavers, opened up from the inside out, and frozen in time for the world to see. The exhibit features a smoker’s lungs, blackened and charred, next to a cup filled with tar from just 90 days of smoking.

There’s a section on the digestive tract where people can learn about the effects of alcohol consumption from seeing fatty, cancerous liver.

Preserving the body through plastination

In 1977, German physician – and Whalley’s husband – Gunther von Hagens made it possible through the invention of plastination, a dissection technique that replaces water from body tissue with liquid polymer, and dried for long-term preservation.

As a traveling museum, Body Worlds has been seen in 150 cities around the world, attracting more than 50 million people.

James Miller, a high school science teacher, has seen the exhibit twice. His students from Agnes Irwin School went on a Body Worlds field trip to the DaVinci Science Center in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

“I find it absolutely fascinating,” he said. “I think that the exhibit, while knowing that they are real people that are in there, they don’t look real based on how the bones, the muscles, all the body parts have been preserved.”

Meanwhile, his students were somewhere between squeamish and awestruck.

“I get joy out of seeing their reactions, whether it’s cringing or not. And when they go, ‘Oh, wow, that’s the thing that we’ve been talking about in class the past couple of months,’” he said. “Yep – there’s the real thing right in front of you!”

Subscribe to The Pulse

Similarly, Ashley LaPat was chaperoning her eighth grade class from Trexler Middle School through the exhibit. She just started teaching body systems in her classroom.

“In August 2021, I was diagnosed with leukemia,” she said, “And, I spent a lot of time in the hospital. I spent a lot of time getting procedures done – even things like bone marrow biopsies.”

While walking through the exhibit, she stopped her class at the exhibit’s section of bones. One was cut open and displayed the inner layer of a femur.

“I was able to show the students,” LaPatexplained, “This is where the bone marrow is. That’s where cells are made.”

The exhibit is largely popular now, but during the early years, it stirred irritation and controversy. In 1993, von Hagens formed the Institute of Plastination as an administrator of body donations for transplants and medical science.

When von Hagens and Whalley wanted to display human cadavers, critics admonished the idea as a circus for the macabre and unethical, particularly in Germany.

“The discussion took place so harshly,” said Whalley, “Because Germans still feel guilty about what happened during the Nazi period. So there is some fear that human remains could be used in an inappropriate manner.”

Donating to the exhibit

More than 20,000 people have signed-up for plastination since. Some donors just want their bodies to be dissected for scientific education, such as cadavers for medical school.

But many do request to be on display for Body Worlds. And Whalley said that even though people sign-up, they can contact the institute if they change their minds. The individual’s primary physician is also notified, along with friends, family or next of kin.

“It’s a declaration of will that you can revoke at any given point in time,” she said. “So it’s not a firm contract that is binding until the end of your life.”

One of the institute’s requirements is for body donors to die of natural causes. A donor cannot be a victim of an accident, homicide, or overdose.

Once someone is deceased, their physician and family member is contacted and the body is flown to Hiedelberg, Germany for autopsy. It’s there where the skin is completely removed, and the anatomical specimen is stripped down to just muscle, tendon and bones.

Whalley doesn’t meet everyone that volunteers for plastination. But she does get to read people’s stories and their reason for donating.

“I remember many years ago we received a body donation from a journalist who happened to report about one of our exhibits,” she said, “and he was then diagnosed of a malignant brain tumor.”

One donor is Teresa Thompson, a former volunteer firefighter from Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, who signed-up in 2005 after visiting the debut in Los Angeles.

She was moved by the exhibit. And as she was leaving, she noticed handout brochures for anyone interested in donating their bodies.

“One of the requirements was to write an essay,” she said. “And that was difficult for me.”

During this time, she worked as an autopsy assistant and a sports massage therapist. She always had a passion for keeping her body healthy and functioning.

“ [In high school] I joined the synchronized swim team, I was on the track team, I was running – I got healthy. And I was doing everything that took a lot of strength. I just felt so powerful in my body.”

In 2001, she volunteered as a rescue worker at Ground Zero on September 11th. She was a volunteer for 12 to 14 hours a day for two months. She remembers having to shower an hour each day to remove the dust and glass after crawling into the World Trade Center wreckage pile for search and rescue.

In her essay, she detailed health complications she suffered since that day, including an asthma diagnosis. She didn’t expect to suffer long-term medical issues. But as she would discover years later, she couldn’t escape the health hazards.

“I had to have parts of my sinuses removed,” Thompson said. “Because they were so packed. So I just thought, if I do end up living a little longer, there’s probably going to be more stuff.”

Initially, when she moved to California, she immediately noticed that the change in altitude was enough to exacerbate her illness.

“It just felt like something was scratching in there all the time,” she said. “Like a cat clawing at your lungs with nails. Just ‘scratch, scratch, scratch.’ It hurt to breathe.”

Thompson decided to donate her body because she believes it might show the dangers of firefighting and the lasting effect of 9/11 — so people can learn from her lived experience when she’s deceased. She’s glad that she made the decision to donate to the Institute.

“Humanity’s errors are not good without studying and learning good choices,” she said.

Body Worlds tries to illustrate people’s lives before death. And while the cadavers cannot use their words, Teresa wants her story to teach an invaluable lesson.

“On the inside, we’re not all exactly the same, but we are the same. The only difference might be with a disease or something. Not the color of the liver. Not the color of a bone, not the color of anything,” she said.

“I feel that showing the body from the inside helps people to learn our similarities are much greater than our differences.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.