Two decades ago, Tom Hanks and ‘Philadelphia’ prompted changing attitudes toward HIV-AIDS

Listen 23:35-

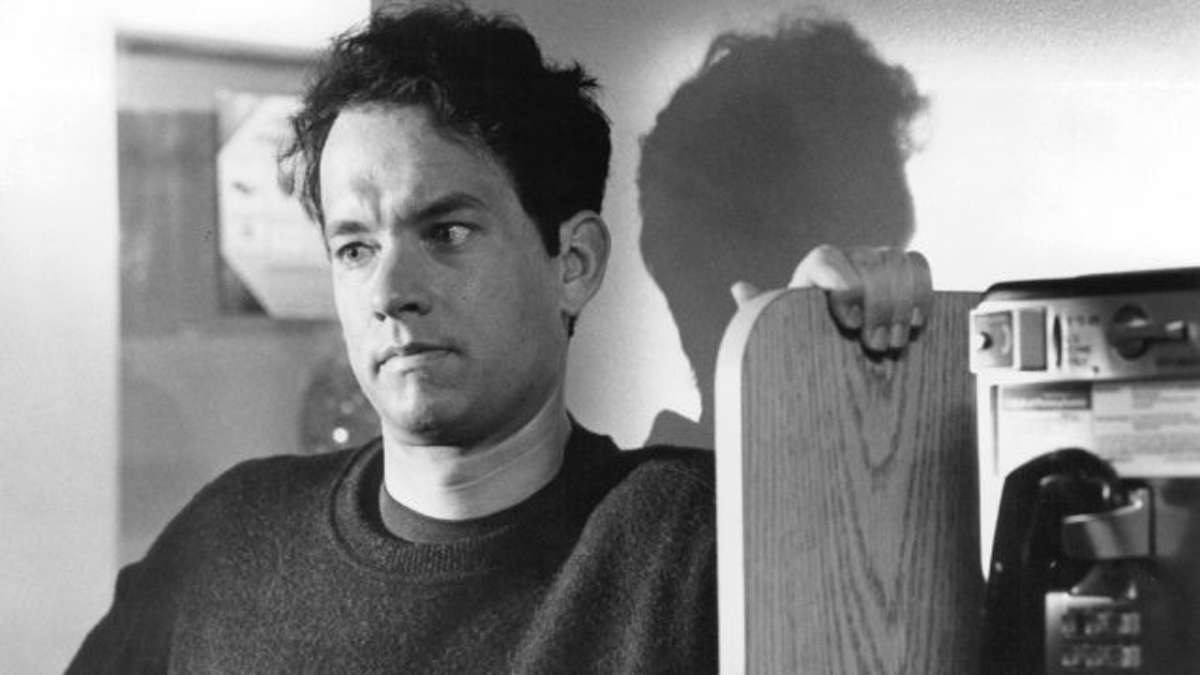

Tom Hanks as Andrew Beckett and Denzel Washington as Joe Miller in the 1993 film 'Philadelphia.' (Photo by Clinica Estetico)

-

Philadelphia AIDS survivor Suellen Kehler holds some of the more than 20 medications and supplements she takes each day to keep her HIV infection under control. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

When she has the energy, Suellen Kehler works on a novel that will tell the story of her life, from naive girl with dreams of marriage and children to AIDS survivor. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Unable to work because of fatigue and pain, Suellen Kehler says her dogs give her a reason to get out of bed in the morning. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Suellen Kehler looks out on a snowy landscape from her Northeast Philadelphia rowhome. When the neighbors found out she was HIV positive, some told their children to stay away. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Instead of a husband and children, I got a sister (Hilda Hernandez, left) and these little dogs who need me. God doesn't always answer your prayers exactly the way you envision them. ~ Suellen Kehler. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Former ActionAIDS Director Ennis Littrell and current Director Kevin Burnes discuss what it was like to be part of the film. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

The ActionAIDS office on Arch Street in 2013. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Tom Hanks as Andrew Beckett in the 1993 film 'Philadelphia.' (Photo by Clinica Estetico)

-

Jonathan Demme directs a scene from 'Philadelphia.' (Photo by Clinica Estetico)

An in-depth look at the making of the film, its impact, and the distance traveled in fighting HIV and AIDS.

Twenty years ago this month, the movie Philadelphia debuted in theaters. It would go on to win two Oscars, Tom Hanks for best actor and Bruce Springsteen for best song, and earn more than $100 million in box office sales.

The film accomplished a lot more than that. It changed the national conversation about HIV-AIDS.

Philadelphia, the city, also played a major role in the film’s success, as a setting and as a source of material. Today, two decades later, the movie still resonates for many, even as people work to write a new script about the disease, in Philadelphia and across the nation.

Philadelphia then

The year was 1993. The Phillies had just won the National League pennant. Ed Rendell was mayor. The Pennsylvania Convention Center had just opened. And, hundreds of thousands of moviegoers were about to meet Andrew Beckett in the movie Philadelphia.

Played by Tom Hanks, Beckett is a bright young lawyer at a high-profile law firm. He’s gay and has HIV. When the firm figures those two facts out, he alleges, it fires him. Beckett wants to sue, but has trouble finding a lawyer to take his case. He ends up with a young attorney, Joe Miller, played by Denzel Washington. What follows is a powerful tale of Beckett’s legal, medical and emotional journey. He wins the case but loses his life.

“I remember there was quite a buzz about it,” recalls Gary Bell, a longtime HIV advocate and director of Bebashi, a health service agency in Philadelphia with a special focus on serving people of color with HIV. “I think the good news was that it got people talking about HIV in a way that they really weren’t, because HIV was always that thing we really didn’t want to talk about.”

Marla Gold, a former assistant city health commissioner, HIV doctor, and public health dean at Drexel University, says Philadelphia managed to do what health leaders had tried and tried to do, yet often fell short: fostering an accurate public awareness about the AIDS epidemic.

“We have a major star, playing a significant role with a visual for HIV, acted out beautifully as a movie that’s award winning,” says Gold. “So this is a lot different than a pamphlet that arrives in the mail and warns you of something. This is real.”

A director on a misson

HIV is a virus that can wreak havoc on a person’s immune system. It’s spread through sexual fluids, blood-to-blood contact, and breast milk. By 1993, when the film came out, AIDS had killed more than 200,000 Americans and nearly 3,000 Philadelphians, according to one news report.

“We got together and tried to come up with a movie that would help push for a cure and save lives,” says Jonathan Demme, who directed and co-produced Philadelphia.

Demme was fresh off winning a best-picture Oscar for Silence of the Lambs. He says he had dear friends dying of AIDS at the time.The challenge, he says, was creating a story that could transcend the huge stigma AIDS carried and pull in the general public. So he turned to rock legends, like Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young, and Hollywood stars like Hanks and Washington.

“We didn’t want to make a film that would appeal to an audience of people like us, who already had a predisposition for caring about people with AIDS,” Demme said in a recent interview with WHYY/NewsWorks. “We wanted to reach the people who couldn’t care less about people with AIDS. That was our target audience.”

For Gary Bell, part of the film’s appeal hinged on the Joe Miller character, the lawyer played by Denzel Washington, who is hesitant to take on Beckett’s case at first because of Beckett’s sexual orientation and HIV status.

“He was a hustler, and he was a guy trying to make a living any way he could,” says Bell, who recalled how Miller transformed as he got to know Beckett, and so too did viewers. “He gave voice to the fear and the stigma to all the things that were holding people in getting involved in this or learning more about it. It was realistic.”

But of all cities, why Philadelphia? For one, it was cheaper to film here. It was the city where Jefferson wrote, “All men are created equal,” and it gave Demme plenty of backdrops that he says portrayed “the good, the bad and the ugly” of real America.

“It’s a fantastic city, and [the film] took it into the homes of Americans and said it can happen here,” says Gold. “And it also said, if it can happen here it can happen in your city and it is happening in your city.”

Philadelphia was fitting in other ways: It was an early center of AIDS activism. The city established a special AIDS office early on, which reported directly to the mayor. Researchers from around the region would contribute to advances in understanding and treating the disease.

Roles with heavy meaning

Philadelphia wasn’t just made in Philadelphia; the film was also made with the people of Philadelphia. About 50 extras in the film had HIV, some with visible signs of the disease. Producers made it a point to employ people with AIDS because of the difficulties they often faced getting jobs.

The local service agency ActionAIDS helped recruit people to be extras. Its office on 12th and Arch Streets also turned into a clinic for one scene, with Hanks’ character walking in to see his doctor and staying for an IV treatment.

“Demme went down the line of who wanted to be extras [at ActionAIDS] and said, ‘OK, you come here, you come here, and of course I was picked,” recalls Suellen Kehler, who had never acted before. Like Hanks’ character in the film, Kehler grew up in Lower Merion on the Main Line. She has straight dark hair, and wearing a turtleneck, she can be seen sitting behind Denzel Washington and Tom Hanks in the courtroom.

Diagnosed with HIV in 1989, Kehler thought she’d be dead within a few years. At one point, sick and desperate for money, she sold her life insurance. Kehler recalls in between film shoots, she and other HIV positive extras would turn to each other for strength and support.

“We would all sit around saying we gotta do whatever’s necessary to stay alive,” she recalled. “So when they do discover that breakthrough pill, we’ll be alive.”

Those breakthroughs were on their way, but tragically, not soon enough for many of them. Within a few years of the film’s release, it was reported that most had died.

This brings an added weight and pride to the film, according to Kevin Burns, director of ActionAIDS.

“For them, this wasn’t a movie. This was how they lived their lives, with courage and great grace. And that wasn’t lost on them,” says Burns. “I think for many, they got some peace and some sense of accomplishment that their struggle was being documented.”

In the spotlight during his Oscar acceptance speech for his role in the film, Tom Hanks focused on those losses and how “the streets of heaven are too crowded with angels. We know their names, they number the thousands for each red ribbon we wear tonight.”

For others, the harsh reality of AIDS made the film too much to bear.

Dr. Michael Braffman, an infectious disease doctor specializing in HIV at the time, who’s still practicing at Pennsylvania Hospital, couldn’t watch the movie.

“I felt like we were living it, day and night. I didn’t want to see another patient die,” he says.

He kept a handwritten memorial list, several pages long, documenting the names of patients he’d lost. It’s a list he has saved to this day.

Life (and bias) imitated art

For Dr. Braffman, the film was difficult for another reason: medical realities aside, patients also faced social and legal challenges similar to Hanks’ character in the film. In the 1990s, Philadelphia had several high-profile AIDS discrimination suits that mirrored Philadelphia‘s plot. Braffman had to go to court and testify in the the case of one of his patients who, like Beckett, was a lawyer.

“One of his employers came and was hounding him and me and everyone at the hospital, about when he was in the hospital, about when he’s coming to work,” recalls Braffman. “Before he left the hospital he was fired, or at least let go.”

Public records shows the individual was Clarence Cain. A judge ruled in 1990 that he’d been wrongfully terminated. Cain died two months later. The credits to the film say the script was partly inspired by a similar case in New York. But there was another case that got even more attention here, that of Scott Burr, initially referred to as Scott Doe.

Burr had worked for “a nationally well-known law firm here in town,” recalls attorney Alan Epstein, who represented Burr. The case started before the film was shot, but went to trial after. During jury selection, anyone who’d seen the film was out. Epstein says with one exception, jurors had one thing in common: fear of casual contact with people with AIDS.

Before the film’s release, the Americans with Disabilities Act took effect. The law strengthened protections for people with HIV. It was used in Scott Burr’s case, as well as countless others that would follow. But Epstein says, as in the movie Philadelphia, Burr’s case wasn’t just about HIV. It was about the stigma it carried, its association as a gay men’s disease. During Burr’s trial, Epstein says, he saw some people go through the kind of transformation Denzel Washington’s character and others went through in the film.

“Once we educated people as to who [Burr] was, what it was like to be a person with AIDS, there was a changing of attitudes. To the extent that I think nine people came down and hugged and kissed Scott at the conclusion of the case.”

Epstein, who’s still practicing employment law today, is struck by the shift in attitudes and changes that have taken place since the trial and the film.

So is Demme.

“What I feel more than anything is I’m glad to see that AIDS doesn’t bear really remotely the stigma which was quite overwhelming at the time, that it did 20 years ago,” he says.

Not only that, but unlike Hanks’ character in Philadelphia, Scott Burr is still alive. Practicing law, in fact, though at the time of the trial his health was quickly slipping, says Epstein. The film was created on the eve of a new era for HIV, giving new hope to Burr, Kehler and many of Braffman’s patients.

“1993 was a long time ago. In HIV, it was an eon ago,” says Dr. Braffman.

Life 20 years later

Twenty years since the film’s release, a prevailing attitude of those involved in the film and in HIV-related work is that things have changed for the better. Even so, many think the film and its themes still resonate in a lot of ways today.

Suellen Kehler shares both perspectives. Today, she may very well be the only extra from the film still living.

“I’m stunned, happy to be alive, but heartbroken to tears,” says Kehler, as she thinks about dear friends, extras in the film, who passed. She’s reminded of this constantly, especially when taking her “lifeline,” or her medicine, either for HIV, its side effects, or other health issues she’s developed along the way.

“And I remember, if I want to be around another 20 years, I need to force these down, one at a time, because my friends couldn’t make it,” says Kehler. “So I fight for them, I know they’re in heaven … watching from heaven, saying you hang in there.”

Kehler’s life is calm and peaceful, a far contrast to the volatility and trauma of her childhood and of the relationship with her former fiancé, who she says contracted HIV while caught up in drugs.

Kehler recently celebrated her 50th birthday. She’s grateful, upbeat even. For her, the film was a starting point in overcoming the emotional weight of her diagnosis, and in helping cope with the loss of her friends. She says she’s now living another chapter — about what it’s like living as long as she has with HIV.

“The movie was a starting point, but there’s so much more in the lives of people with HIV,” says Kehler.She’s working on a book. Kehler had always dreamt of getting married, having kids. While things didn’t turn out that way, she attributes her longevity to her two other “kids,” Pomeranians, her best friend Hilda, and her religion.

“Yes, medicine is important but I state wholeheartedly you must have faith in something,” says Kehler. “God does give us everything we want, but not exactly how we see that we want them.”

In her condition, though, fatigue and side effects are also constant companions. If she can do the laundry and fold the clothes, she says, that makes it a good day.

‘A lot has not changed’

Kehler says, no doubt, life today is less isolated for her and others with HIV. She credits the film for a lot of that. After it came out, a coworker who’d moved her desk away pushed it closer again. Even so, Kehler says she’s reminded almost daily that the stigma is still out there.

“I personally see for myself that a lot has not changed,” she says, pointing to how some neighbors won’t let their kids near her house. Last year when she was hospitalized, she says staff wouldn’t touch her skin. Some people taunt her best friend, who’s gay.

Ronda Goldfein, director of the AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania, says Kehler isn’t the only one still encountering the effects of stigma.

“When the movie came out, we all thought it was this groundbreaker,” she recalls. “There was this prevailing thought, wow, there’s a movie from a big studio that says it’s wrong to discriminate against AIDS. This is it, this is going to make all the difference, we won’t see these cases.”

And to be sure, Goldfein says, these days an Andrew Beckett wouldn’t have any trouble finding a lawyer to take his case. The Americans with Disabilities Act, passed in 1990, gives legal backing to the kind of suit Beckett brought. Philadelphia also has its own laws to strengthen workplace protections for people who are gay.

Even so, Goldfein says she gets three to five calls each week “that somebody’s been treated differently simply because they have a virus, that they can’t get health care because a doctor or receptionist is afraid of them. That the kid won’t play with their kids…this stuff is happening all the time.”

Philadelphia now: Advances and challenges

One thing that’s not happening anywhere near as often as in 1993 is people dying of AIDS.

In 1993, when audiences first learned the Andrew Beckett character in the film had AIDS, they could conclude he would die by film’s end. Michael Braffman, the HIV doctor at Pennsylvania Hospital, stopped adding names to his memorial list a long time ago, thanks to major advancements in antiretroviral treatments.

“And all of a sudden by the mid 90s people stopped dying.” he says. “The home care company said, ‘How come you’re not sending us patients anymore?’ And we said, we have no more patients to send you, they’re actually living. We almost never lose patients. They die of heart attacks; they die of cancer; they die of auto accident;, they die of old age.”

The relentless efforts of AIDS activists, and federal and private support for HIV have also made it easier for people to get medicine, and live normal long lives. The diagnosis is no longer a death sentence; it is a chronic illness.

Investment in HIV research has also grown, with area institutions working to advance understandings of the disease. This month, efforts aimed at finding a cure got a federal funding boost. Scientists have also learned more about HIV transmission. Preventing mother to child cases is one big success.

Yet, the disease is still spreading.

“There’s a lot of people who don’t know they have this epidemic,” says Boston Canery, a local prevention specialist who can be found in Philadelphia neighborhoods passing out condoms, raising awareness about the disease.

“We’re hoping we can find positive people so we can link them to care and give them medicine so they can live longer.”

Canery is soft-spoken and tired. His phone rings “24/7” with people calling for help. He goes out at night, offering support to those who’ve spiraled downhill, often homeless, after receiving a diagnosis. He can also be found at community spaces, conducting rapid HIV tests. It requires a sample of a person’s saliva sample and about 20 minutes of waiting time.

Nationwide, there are an estimated 50,000 new HIV infections a year. Here in Philadelphia, the per capita rates of new HIV infections are three times the national average, with roughly 700 to 800 newly reported cases in the city each year.

Some headway has been made. A longstanding needle exchange has been credited for curbing HIV infections among people who inject drugs.

But Canery says along with fear, he’s fighting a lot of misinformation, especially among young adults, about how you can get the virus.

“I keep telling them, there’s four ways you can come into contact with HIV,” says Canery, who is particularly concerned with all the new HIV infections cropping up among young adults. “And they’re like, ‘Not by hugging?'”

This worries Gary Bell, director of Bebashi, who says even “educated, smart” people he knows think the disease is fully tamed, pointing to things like the continued good health of basketball legend Magic Johnson.

“The problem is that up to 75 percent of people who are HIV positive are not getting the right level of care, meaning they either don’t know their positive, they’re in and out of care or they’re just not getting the kind of quality care that keeps their viral load down.”

With new understandings about how treatment can curb new infections by keeping the virus under control, “Prevention is treatment’ has become a motto of outreach efforts in the city, according to Bell.

HIV is also a disease that stalks the poor.

Kevin Burns sees that trend, as the current director of ActionAIDS, Burns says the virus just piles up on top of other challenges people face daily, like mental health needs or finding a stable place to live:

“The reality today is housing is treatment because they can’t access treatment and have it be effective if their homeless.”

Housing, for example, is one area of focus for activists in Act Up, a longstanding AIDS group that’s still has a chapter in Philadelphia today.

For Marla Gold, a former assistant city health commissioner, HIV doctor and now professor at Drexel’s school of public health, the medical advances since the movie aired “are astounding.”

Yet she says despite the progress, even if a cure for AIDS were found, the health system, from which so many poor residents are isolated, would struggle to get it to everyone who needed it.

“So we have to ask ourselves why can’t we get through that last hoop to prevent this disease?”

Grounds for hope

Still, the contrast between the vintage 1993 Philadelphia shown in Jonathan Demme’s film and the Philadelphia of today offers many on the frontlines of HIV major grounds for hope.

That’s certainly the case for 25-year-old Rafael Alvarez.

Around Northeast Philadelphia and elsewhere, corner shops, street corners and local newspapers have featured posters of him and other community members aimed at putting a positive slant on people who are gay and people who have HIV. The city-backed effort, according to Alvarez, is twofold: spreading awareness about HIV in the Latino community, where infection rates are worrisome, and pushing back against the notion that the community rejects people who are gay.

“Perceptions are reality,” says Alvarez. “And if the perception of a community is negative or labeled in ignorance, then that’s what’s going to be the reality.”

Alvarez recently watched the film Philadelphia again, and says it was still moving. It also reminded him of his own family’s struggles, with a great aunt who died of AIDS in the nineties. He wasn’t allowed to see her.

Watching the film, Alvarez says he’s struck by how Hanks’ character is portrayed as a real person with friends and family who loved him.

“He [Hanks’ character] is not ‘AIDS.’ He’s a person, and I think that gave him his humanity back,” says Alvarez. “And I think that is the lasting impact.

Today, Alvarez views his work and that of others as a follow-up to the film.

“It definitely put in perspective why we have to fight and change,” says Alvarez. “The work we’ve done, we have changed HIV. We genuinely have done that. Health care has changed it. But there’s so much work to be done. And that’s what it [the movie] has affirmed for me.”

For Suellen Kehler, the HIV positive extra in the film, her life is also one of hope, as she spends her days writing and documenting her own story, one about life with HIV, that picks up where the film left off. When her script is done, she says, Tom Hanks will have a part waiting for him.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.