100 years later, medical licensing exam still a herculean task

Listen

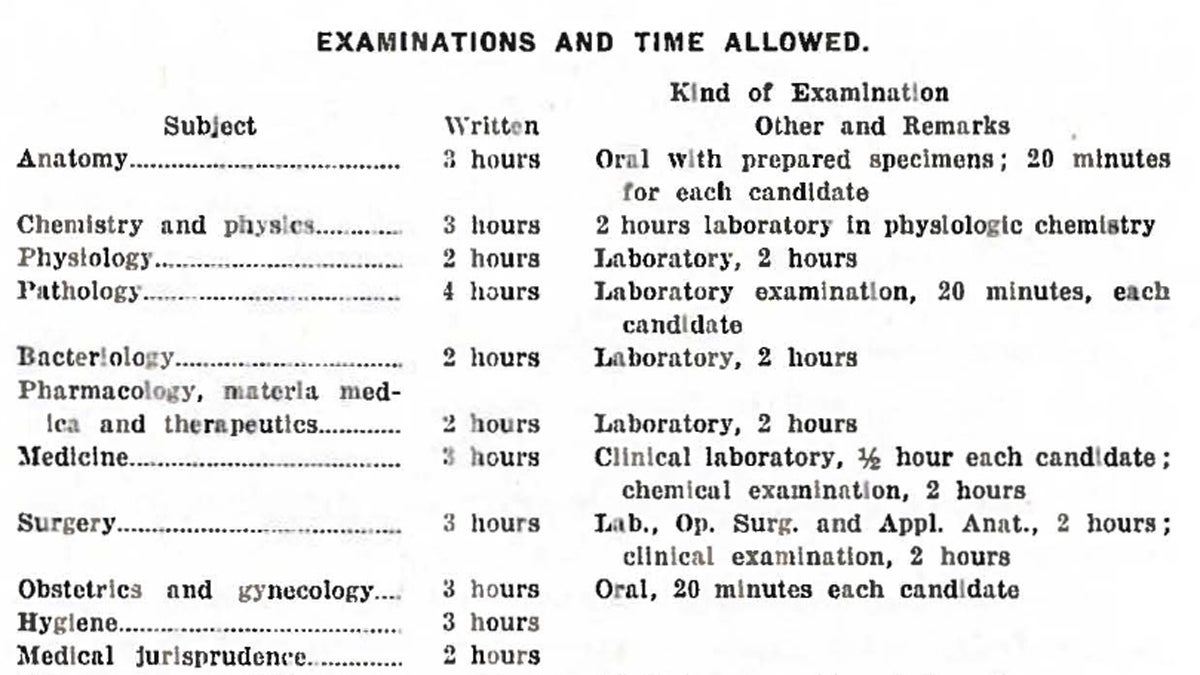

The schedule for the first National Board examination given in 1916. (Photo courtesy of the National Board of Medical Examiners)

The National Board of Medical Examiners has spent the past century putting doctors through the wringer.

In the late 1800s, William Rodman, a well-known surgeon and professor, left the University of Kentucky to take a job in Philadelphia. Upon arrival, he was appalled by two things.

“First of all, he had to take another exam,” says Donald Melnick, president and CEO of the National Board of Medical Examiners. “This prominent author of textbooks, educator came to Pennsylvania, and they said you have to take our exam to get a license.”

Second, Pennsylvania’s exam at the time was, well, “he thought it was an awful exam.”

Rodman’s experience would shape the rest of his life. For the next two decades, he spearheaded an effort to create a national exam for doctors—a test of such rigor and quality that the individual states would gladly accept a passing score in place of their own exams.

Unfortunately for him, this wasn’t exactly an era of broad collaboration.

“Just like today, the 10th Amendment’s focus on the rights of states to manage their own affairs is a pretty powerful political dynamic…back in 1915, it was the same way,” says Melnick. “And so the notion of a national—not a federal, but a national—entity being involved in assessing qualifications for licensure was seen as anathema by many, and an intrusion on states’ rights and state autonomy.”

Recognizing a political gauntlet, Rodman instead proposed a strictly voluntary exam that states and medical students could consider for licensure.

The idea got early backing from the United States military, which was closely watching World War I break out in Europe. A high quality test, the armed services figured, could help ensure the best doctors were identified to serve at the front.

In 1915, the National Board of Medical Examiners was established in Philadelphia. Its first exam—consisting of essays, oral questions, as well as a bedside examination of skills—was administered in Washington the following year to ten aspiring physicians from across the country.

“My favorite item from the first exam,” says Melnick, “was that a student was given a tray with two pieces of fresh dog intestine. They had to suture the ends of that intestine together, and then one end of was clamped off and they put water in it to a certain water pressure, and if the anastomosis line did not leak, they passed that item.”

From dogs To bubbles

Over time, the concept of a national exam began to gain traction. So much so that by 1943, all but three states recognized the NBME’s exams as an alternative to their own licensing system.

In the 1950s, however, a new type of test question was coming into vogue—a simpler, more black and white way to measure knowledge: the multiple choice.

After much consideration, NBME phased this new format into its exams. It did not go over well.

“Not only did we hear pushback, but a large number of the states that recognized our certification for licensure declined to recognize this new fangled superficial exam that had just multiple choice questions,” says Melnick.

A dozen states opted out of the national system, but the NBME didn’t reverse course. For the next 40 years, the format remained consistent, with three multiple choice examinations taken at intervals during medical school and residency training.

Then, in the early 2000s, another controversial change. A graded patient interaction—one of the original components from the 1916 exam—was added back into the second stage of testing. But this time, it had more to do with assessing interpersonal skills than strictly technical ones.

“It is just amazing how long it’s taken for the concept of communication skills by physicians in their encounters with patients to be taken seriously,” says Ruth Hoppe, a consultant for the NBME.

For those of us on the receiving end of a stethoscope, these abilities are crucial, and not just because they make us feel more human. Hoppe says research consistently finds patients have better health outcomes when the doctor-patient relationship is bridged with good communication.

A century ago, that idea would have been laughed off, says Kim Edward LeBlanc, who manages the clinical skills portion of the test for the NBME.

“You went to the doctor, you didn’t know what you had. You left, you didn’t know what you had, but you had a bottle of medicine,” he says. “So those days, for the most part, are fortunately gone.”

As part of today’s test (now formally called the United States Medical Licensing Exam) each doctor spends a day in a facility seeing “standardized patients.” These actors fake various symptoms following carefully scripted scenarios. The interaction, along with the diagnosis or recommended follow-up treatment, are given a pass/fail grade.

Judging by the results, most doctors are now pretty good at this. In 2014, 96% of U.S. medical school graduates passed this portion on the first attempt. (The pass rate for foreign medical school graduates, who must pass the USMLE in order to practice here, was 80%.)

Pass rates for all components of the NBME tests are in the mid-90s, which is, in part, a reflection of just how much med students cram for these things.

A smart doctor, or a good one?

The weeks before medical students take the first step of the USMLE are generally not enjoyable ones.

“Pretty much just 80 hours in the library, plus breaks and sleeping now and again, eating, and ideally, taking care of yourself. But you tend to sacrifice one or the other,” says Priya Joshi.

Like many of today’s doctors, she calls the “Step 1” portion of the exam, which is usually taken after the second year of medical school, the single biggest test doctors face. Hospitals heavily weight the Step 1 score when determining who they offer residencies to, and a prestigious residency can have deep ripples in a career.

Not everyone loves having so much hang on a such a single thread.

“The general idea is, if your score is higher, you are a smarter doctor,” says Joshi. “But I guess the question would be, what makes a good doctor? And I don’t know if that necessarily correlates with a higher Step 1 score.”

Joshi recently graduated from Sidney Kimmel Medical College, and will start her residency at Penn in a few weeks. She’s says studying for the USMLE did tie together the endless lectures and powerpoints endured during the first two years of school.

“There is something nice about your family members calling you and you are like, ‘Oh, I know what kind of rash you have on your back.’ Cause you finally get it….and that feels really good,” says Joshi.

Of course, it’s easy to say that after the test is over.

Today, the NBME is recognized by all 50 states, though it took until 1994 before Texas came on board. That would have pleased Dr. William Rodman, who never got to see the test he fought for in action. Rodman died suddenly in 1916, just months before the first exams were given.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.