‘Lying through truth’: Misleading facts fuel vaccine misinformation

A worker prepares to give a COVID-19 vaccine at the Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, Calif. on March 18, 2021. (MediaNews Group/Long Beach Press/MediaNews Group via Getty Images)

The odds of dying after getting a COVID-19 vaccine are virtually non-existent.

According to recent data from the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention, you’re three times more likely to get struck by lightning.

But you might not know that from looking at your social media feed.

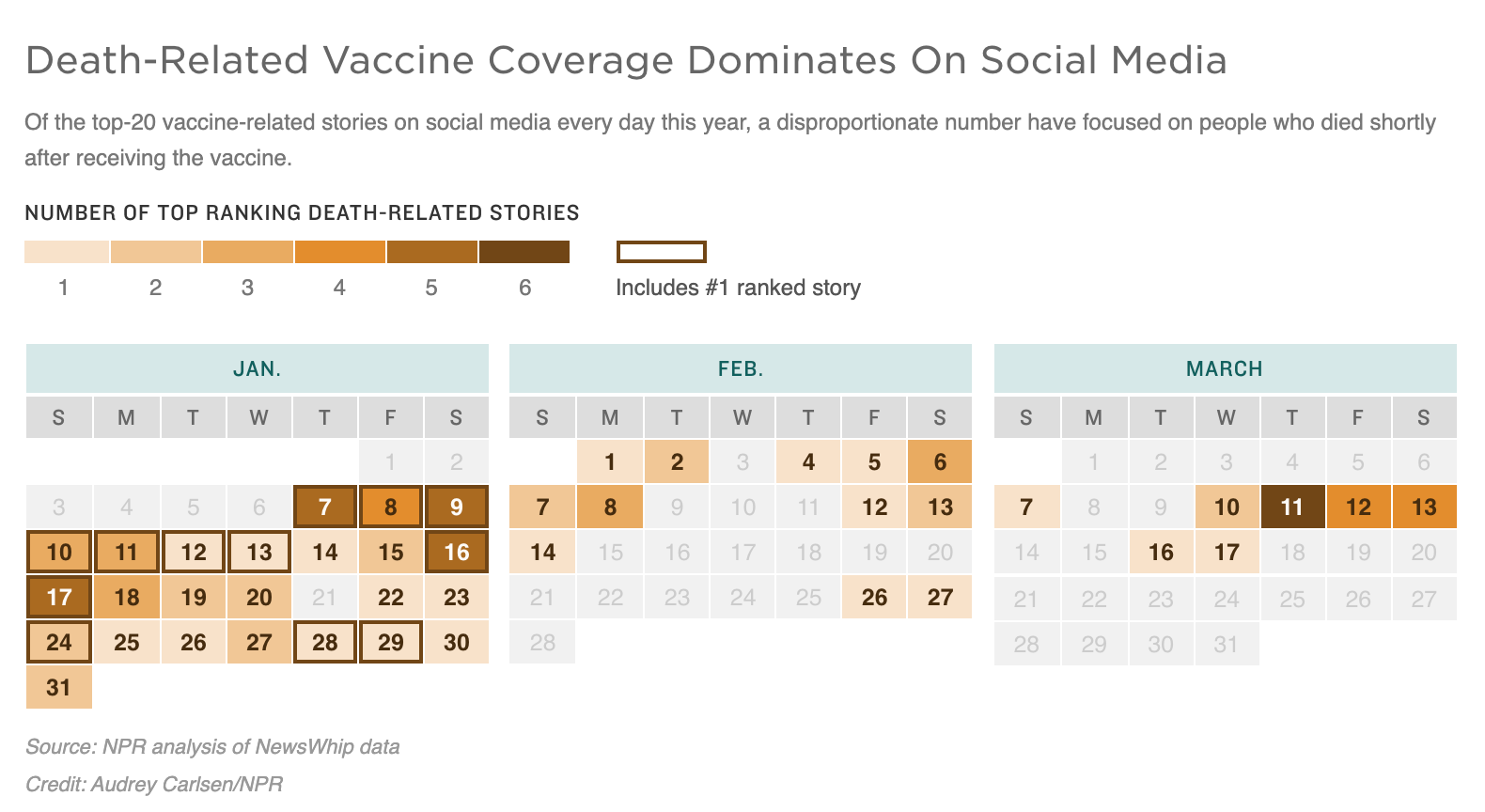

A new NPR analysis finds that articles connecting vaccines and death have been among the most highly-engaged-with content online this year, going viral in a way that could hinder people’s ability to judge the true risk in getting a shot.

The findings also illustrate a broader trend in online misinformation: with social media platforms making more of an effort to take down patently false health claims, bad actors are turning to cherry-picked truths to drive misleading narratives.

Experts say these storylines are much harder for companies to moderate, though they can have the same net effect of creating a distorted and false view of the world.

“It’s a really insidious problem,” said Deen Freelon, a communications professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. “The social media companies have taken a hard line against disinformation; they have not taken a similarly hard line against fallacies.”

To date, the CDC’s reporting system has not received evidence linking any deaths directly to vaccines.

And yet, on almost half of all the days so far in 2021, a story about someone dying after receiving a vaccine shot has been among the most popular vaccine-related articles on social media, according to data from the media intelligence company NewsWhip.

That includes the year’s most popular vaccine story: a South Florida Sun Sentinel article, which was republished in the Chicago Tribune, about a doctor who died a few weeks after receiving the vaccine.

The story explicitly notes there has been no link found between the shot and his death, but it has received almost 5 million interactions on Facebook and Twitter nonetheless.

“This problem is not theoretical. It’s not hypothetical,” said Sarah Roberts, an information studies professor at UCLA. “This thorny issue directly lands in this gray area of an emergent information crisis that has really clear real world implications.”

Few deaths, many clicks

By just about any metric, it’s clear stories linking deaths to vaccines have spread in such a way that wildly overstates real numbers.

Among the more than 85 million people in the U.S. who have now received at least one vaccination shot, less than .0018% of shot recipients have died sometime afterward.

Even that small number includes people who were vaccinated while also suffering from other health conditions.

Whether they have a vaccine or not, roughly 8,000 people die in the U.S. every day. And as more people get vaccinated, more vaccinated people will continue to die from unrelated causes, which the pharmaceutical company Pfizer alluded to in a statement earlier this year.

“It is important to note that serious adverse events, including deaths that are unrelated to the vaccine, are unfortunately likely to occur at a similar rate as they would in the general population,” the statement said.

But Freelon, of UNC-Chapel Hill, says when it comes to conspiratorial thinking, stats and nuance often don’t matter as much as tragic stories.

“This is something that we see repeatedly with human cognition,” Freelon said. “It’s the emphasis on the breathless anecdote and then the discounting of statistics that are much more representative.”

The largest spike in death-related stories came at a critical time in the vaccine rollout.

In January, as the average number of shots administered quadrupled and people frantically searched for information as they considered whether to be vaccinated, this was also the time people were most likely to encounter a story linking a death to vaccination, according to the NPR analysis.

Every day from Jan. 7 through Jan. 20, at least one story linking a vaccine to a death was among the 10 most-engaged-with stories about vaccines.

NPR analyzed NewsWhip’s data by looking at each day’s most-engaged-with stories that included the word “vaccine” in the headline, summary, or metadata.

Engagement encompasses how many times an article was shared, commented on, or liked, across Facebook, Pinterest, and much of Twitter.

On some days, like January 16 and 17, and March 11 and 12, 25 percent or more of the top vaccine stories on social media were about a person who died after being vaccinated.

This is not because many more people died during these periods; rather it’s the result of multiple news outlets writing articles about the same small number of deaths and reaching a larger audience.

On March 11 for instance, all six of the stories in the top 20 most-engaged-with vaccine stories were about the same Utah woman who died four days after receiving her second vaccine dose.

One Facebook page with 20,000 followers posted a link to the article, with the caption “I’ll pass on the vaccinations. I could care less of anyone’s opinion… this is horrifically sad.”

Another page, with 10,000 followers, posted it saying “very concerned about those getting the poke.”

A few days later however, the Utah Office of the Medical Examiner issued a statement saying “there have been NO DEATHS caused by the COVID-19 vaccines to date in Utah.”

In one of the news stories that was shared with anti-vaccine messages, the actual text of the article described how the father of the woman who died still decided to get the shot himself.

Exploiting the grey area

The difficulty in moderating these sorts of stories comes from their truthfulness. A woman did die four days after receiving the vaccine in Utah. But there wasn’t any causal relationship, according to the state’s medical examiner.

Social media companies have made it clear that when it comes to sharing true-but-misleading information, they don’t want to wade in.

“Content can’t always be clearly divided into helpful and harmful,” wrote Facebook head of health Kang-Xing Jin, in a recent San Francisco Chronicle op-ed. “It’s hard to draw the line on posts that contain people’s personal experiences with vaccines.”

But peddlers of misinformation, and even American adversaries, have discovered this gap in content moderation.

Russian state media like RT and Sputnik News, shared more than 100 stories linking the Pfizer vaccine to subsequent deaths of recipients, according to a recent report by the Alliance for Securing Democracy.

It’s a phenomenon dubbed “lying through truth” by Bret Schafer, who wrote the report.

“The [social media] platforms look at an individual tweet from RT saying 23 people died in a nursing home after taking the Pfizer vaccine and they can’t do anything about it because it is technically true, while being wildly misleading,” Schafer said. “That seems to be the new strategy.”

On Thursday, the CEOs of Facebook, Twitter, and Google will appear at a U.S. House hearing centered around misinformation that spreads on their platforms.

In his opening remarks, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg will tell lawmakers about the myriad ways the company is fighting to “keep harmful misinformation about COVID-19 from spreading,” but the statement focuses only on false claims, and makes no mention of these sorts of grey areas.

About 30% of Americans continue to express some hesitancy around getting a COVID vaccine, according to a recent NPR/PBS Newshour/Marist poll.

Ann Bostrom, an expert on risk perception at the University of Washington, says many of these people are judging the situation incorrectly.

For someone to correctly calculate the real risk involved in getting a shot, she says, they need to consider the hundreds of thousands of people who have died because they were not vaccinated against COVID-19, not just a random headline.

“We rarely get the contextual information we need,” Bostrom says. “And it’s really hard to judge the importance of something without that information.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)