Ketamine, a promising depression treatment, seems to act like an opioid

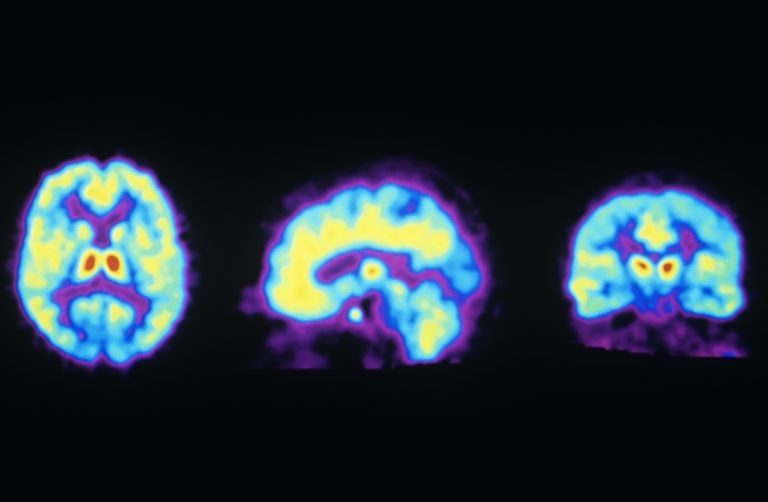

These PET scans show the normal distribution of opioid receptors in the human brain. A new study suggests ketamine may activate these receptors, raising concern it could be addictive. (Philippe Psaila/Science Source)

A new study suggests that ketamine, an increasingly popular treatment for depression, has something in common with drugs like fentanyl and oxycodone.

The small study found evidence that ketamine’s effectiveness with depression, demonstrated in many small studies over the past decade, comes from its interaction with the brain’s opioid system. A Stanford University team reported their findings Wednesday in The American Journal of Psychiatry.

“We think ketamine is acting as an opioid,” says Alan Schatzberg, one of the study’s authors and a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University. “That’s why you’re getting these rapid effects.”

Until now, most researchers have attributed ketamine’s success to its effect on the brain’s glutamate system, which is involved in learning and memory. The opioid system, in contrast, controls pain, reward and addictive behaviors.

Ketamine is an anesthetic that is frequently given to children in the emergency room. It is also a popular but illicit party drug that can cause an out-of-body experience at high doses.

And in the past few years, ketamine has seen increasing use as an off-label treatment that doctors prescribe for patients with severe depression that doesn’t respond to other drugs. Unlike conventional antidepressants like Prozac, which can take weeks to work, an infusion or nasal administration of ketamine typically produces results in hours.

The new study’s findings suggests that taking ketamine for depression could lead to abuse or addiction, says Schatzberg, who has financial ties to several drug companies. Ketamine has a less potent effect on opioid receptors than drugs like fentanyl or oxycodone, he says, “but that doesn’t mean it’s safer.”

Other researchers say the study’s implications aren’t so clear.

“The results are quite intriguing,” says Carlos Zarate Jr., an investigator at the National Institute of Mental Health who has been studying ketamine’s effects on depression for more than a decade. “However, this study is preliminary and its results need to be replicated.”

The new study is “interesting and exciting,” says Ronald Duman, a professor of psychiatry and neurobiology at Yale University who has published research showing how ketamine causes brain cells to form new connections.

But Duman isn’t convinced that ketamine’s effect on the opioid system is the key to its effectiveness in treating depression. He notes that ketamine’s effect on the brain’s glutamate system is quite powerful, while the drug has “a relatively low affinity for opiate receptors.”

The Stanford team decided to conduct its study after seeing research that suggested drugs that work on the glutamate system alone aren’t very effective antidepressants, Schatzberg says. The researchers also knew that opioid drugs had once been used to treat depression but were largely abandoned because of concern about abuse.

So the team designed an experiment that would treat patients with depression in two ways. The first was by giving them an infusion of ketamine alone. The second involved giving each patient the drug naltrexone, which blocks the effects of opioid drugs, before the patient got an infusion of ketamine.

An analysis of a dozen patients who got both treatments showed a dramatic difference. Seven of the 12 saw their depression symptoms decrease by at least 50 percent a day after they got ketamine alone. But when they got naltrexone first, there was “virtually no effect,” says Carolyn Rodriguez, one of the study’s authors and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford.

Rodriguez, who has pioneered the use of ketamine to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder, says the study doesn’t prove that the drug works primarily through the brain’s opioid system. Instead, she calls the result “the beginning of a conversation” and says it “highlights that ketamine’s mechanism of action is complicated.”

Rodriguez has served as a consultant for several drug companies including Allergan, which is developing a depression drug that acts like ketamine in the brain.

One possibility is that ketamine’s effect on opioid receptors may provide immediate but short-term relief of depression symptoms, Rodriguez says, while the drug’s effect on the glutamate system may be what makes that relief last for a week or more.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))