Justice Ginsburg’s death sets up political battle in the Senate

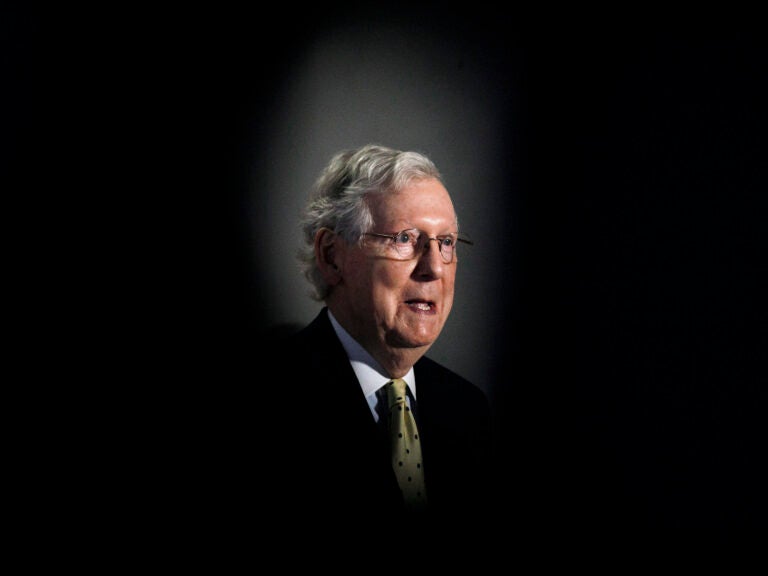

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell will likely preside over the political fight over a vacant Supreme Court seat. (Jacquelyn Martin/AP Photo)

The death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Friday at age 87 will inevitably set in motion what promises to be a nasty political battle over who will succeed her at the Supreme Court.

Just days before her death, as her strength waned, Ginsburg dictated this statement to her granddaughter Clara Spera: “My most fervent wish is that I will not be replaced until a new president is installed.”

She knew what was to come. Ginsburg’s death will have profound consequences for the court and the country. Inside the court, not only is the leader of the liberal wing gone, but with the court about to open a new term, Chief Justice John Roberts no longer holds the controlling vote in closely contested cases.

Though he has a consistently conservative record in most cases, he has split from fellow conservatives in a few important ones, casting his vote with liberals for instance, to protect at least temporarily the so-called DREAMers from deportation by the Trump administration, to uphold a major abortion precedent and to uphold bans on large church gatherings during the pandemic. But with Ginsburg gone, there is no clear court majority for those outcomes.

Indeed, a week after the upcoming presidential election, the court is for the third time scheduled to hear a challenge brought by Republicans to the Affordable Care Act, known as Obamacare. In 2012, the high court upheld the law by a 5-4 ruling, with Roberts casting the deciding vote and writing the opinion for the majority. But this time the outcome may well be different.

That’s because Ginsburg’s death gives Republicans the chance to tighten their grip on the court with another appointment by President Trump, allowing conservatives to have a 6-3 majority. And that would mean that even a defection on the right would leave conservatives with enough votes to prevail in the Obamacare case and many others.

At the center of this battle will be Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. In 2016, he took the unprecedented step of refusing for nearly a year to allow any consideration of President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, Judge Merrick Garland, a widely respected centrist liberal whom Republicans had previously praised as the kind of nominee they would like from a Democratic president.

Back then, McConnell’s justification was the upcoming presidential election, which he said would allow voters a chance to weigh in on what kind of Supreme Court justice they wanted.

But now, with the tables turned, McConnell has made clear he will not follow the same course. In a statement Friday, McConnell said Trump’s nominee to fill the vacancy left by Ginsburg’s death would receive a vote on the Senate floor.

“In the last midterm election before Justice Scalia’s death in 2016, Americans elected a Republican Senate majority because we pledged to check and balance the last days of a lame-duck president’s second term. We kept our promise. Since the 1880s, no Senate has confirmed an opposite-party president’s Supreme Court nominee in a presidential election year,” McConnell said in a written statement.

“By contrast, Americans reelected our majority in 2016 and expanded it in 2018 because we pledged to work with President Trump and support his agenda, particularly his outstanding appointments to the federal judiciary. Once again, we will keep our promise.”

It’s unclear of the timing of the vote, and the traditional nomination process takes longer than the amount of days left before the November election.

McConnell’s tactics have worked well for the GOP in the past, firing up the Republican base, and proving a major factor in Trump’s 2016 election. With a Republican in the White House, McConnell then stripped from the Senate rule book just about every procedural rule that allowed the minority party to slow down controversial nominees.

So what happens in the coming months will be bare-knuckles politics, writ large, on the stage of a presidential election.

For some Republicans facing reelection, Ginsburg’s death puts them between the proverbial rock and a hard place. A vote to confirm another Trump nominee could, for instance, doom the reelection prospects of Sens. Susan Collins of Maine and Cory Gardner of Colorado. But a vote against confirmation could infuriate conservative Republicans in their states, depressing both campaign contributions and turnout for them.

But even if both were to vote against confirmation, a huge assumption since they have never voted against a Republican Supreme Court nominee, the Democrats would still need two more Republican votes. They might get Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, but they would still be one vote shy because of Vice President Pence’s tie-breaking vote. It’s hard to see where that extra vote would come from. Tennessee’s Lamar Alexander is the most moderate of the retiring Republican senators, but he is McConnell’s closest friend in the U.S. Senate.

It will be a fight Ginsburg had hoped to avoid, telling Justice John Paul Stevens shortly before his death that she hoped to serve as long as he did — until age 90.

“My dream,” she said in an interview, “is that I will stay on the court as long as he did.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))