How Tulsa race massacre shaped today’s most successful Black CEOs

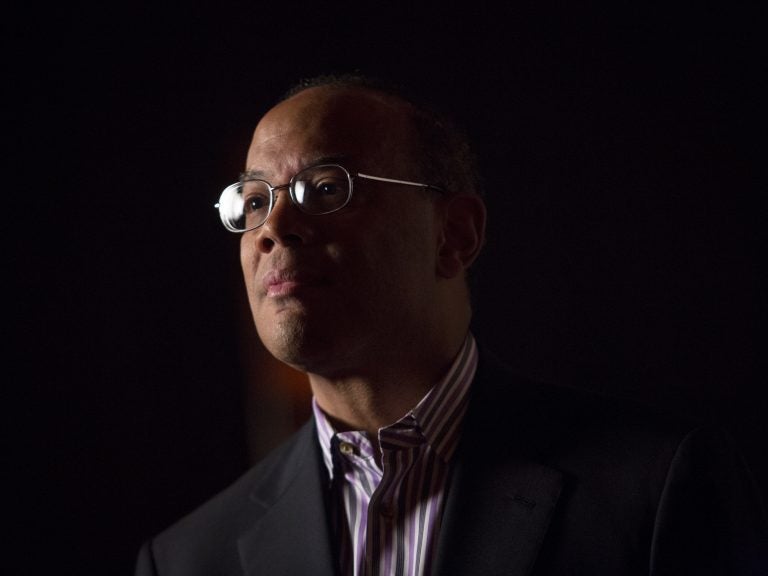

John Rogers, co-CEO of Ariel Investments, stands for a Bloomberg Television spot in Atlantic City, N.J., July 22, 2013. Rogers tells NPR about the emotional and financial impact the Tulsa riots had on his family. (Scott Eells/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

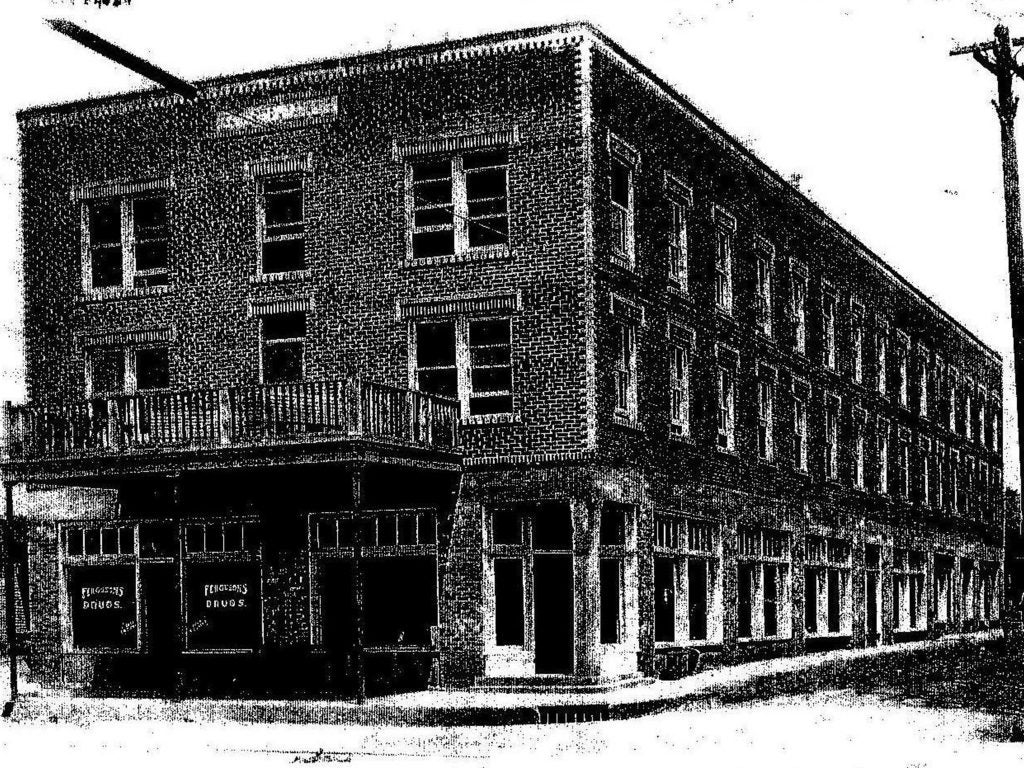

J.B. Stradford was a pillar of Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood in 1921. He owned several businesses and his Stradford Hotel was one of the the largest Black-owned hotels in the United States.

It all vanished in the space of a couple of days.

The riots that engulfed Tulsa a hundred years ago killed hundreds and destroyed scores of businesses in the then thriving neighborhood known as Black Wall Street.

Today, Stradford’s great grandson is a well known Black investor in the modern Wall Street, and he remembers the emotional – and financial – impact the riots had on his family.

“Over time, we think it would have compounded to over $100 million,” says John W. Rogers Jr., who is co-CEO of Ariel Investments, reflecting on the wealth that his family could have accrued.

“We think it would have been real, serious wealth that J.B. Stradford would have been able to create, and then to share with his descendants,” he adds.

Before the Tulsa Race Massacre, Greenwood was awash with oil money. It was a place of prosperity and possibility, and Stradford was an outspoken advocate for equality.

“Tulsa attracted these kind of dynamic, independent-thinking, strong-willed leaders, who were not going to sit idly by and be dictated to, but were going to push back,” Rogers says.

Black Wall Street was a commercial center, with restaurants, movie theaters, and barber shops, and according to Rogers, “Every profession was represented there.”

What made Greenwood so special is the money stayed in the community. Everyone did business with each other.

“They were all in it together,” Rogers says. “They gained an enormous amount of confidence in what they could do as business leaders, the kind of educational opportunities they would be able to give their kids,” he adds. “You know, to build multi-generational wealth was really the dream.”

For hundreds of families, that never came to pass.

“The wealth creation that was missed is just absolutely incredible,” says Kenneth Chenault, the former CEO of American Express, who still remembers when he heard about the Tulsa Race Massacre for the first time.

Chenault was in high school, and a relative described the violent attacks.

“This was absolutely brutal what happened,” he tells NPR. “I think what’s very important to understand is the fear that Blacks had, that anything they had was fragile, because it could be taken away from them.”

Chenault, who joined American Express in 1981 and eventually headed it for nearly two decades, marvels at what Greenwood’s residents managed to build in Tulsa “despite the prejudice and racism that they endured” and the “extreme odds.”

During his long career in business, Chenault has thought about the lives lost, and the consequences of so many businesses ruined and so much wealth destroyed.

He was one of the first Black CEOs of a Fortune 500 company, which continues to be a very small club.

“What I certainly would have liked to see happen, and I certainly believed it would, was the number of Blacks as CEOs would have increased,” he says.

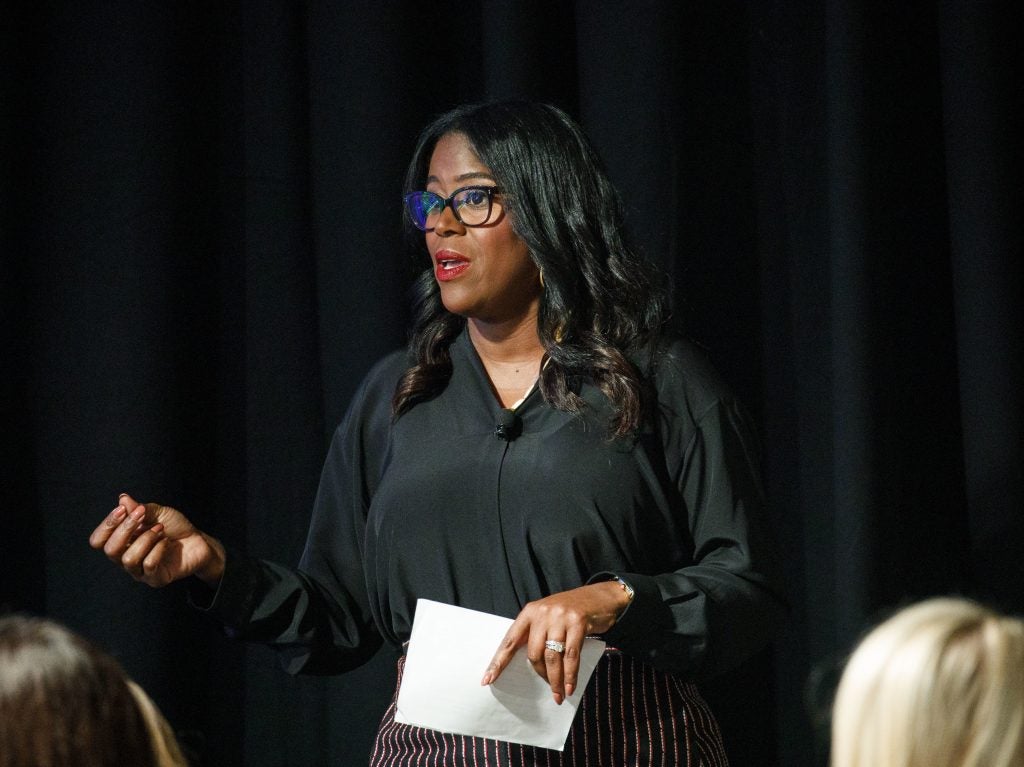

In fact, that number is getting smaller. When Ken Frazier steps down from Merck next month, there will be four Black CEOs of Fortune 500 companies. One of them is Thasunda Brown Duckett, who runs TIAA, a financial services firm that manages more than $1 trillion in assets.

The Tulsa Massacre was not something Duckett learned about when she was in school, growing up in Rochester, N.Y, or Houston. But now, it is something she thinks about every day, when she goes into her office.

“When you first walk in, there is a poster of Black Wall Street, because I represent Black Wall Street going forward, and the future and the promise of what was denied 100 years ago,” Duckett says.

She is one of two Black women running Fortune 500 companies, and Duckett says that what happened in Tulsa, is part of the reason why there aren’t more executives who look like her in corporate America today.

Insurers denied survivors’ claims, and so did the government, which contributed to an erosion of trust by Blacks in the financial system. Duckett says that distrust has compounded over the last century.

“You know, we talk a lot about structural and systemic racism, and I think that is what the Tulsa Massacre shows us,” she says. “It gives a real face and a narrative to what that really means.”

Duckett is trying to restore that trust in the financial system. There has been progress in getting more Black people represented at companies and in Wall Street.

For instance, there are more Black board members at public companies but Tulsa serves as a reminder of how quickly things can be lost.

When Black Wall Street burned, Stradford couldn’t save his businesses. He was taken into custody, and charged with rioting. But he escaped, first to Kansas, then to Illinois.

“He was never able to replicate the success he had in Tulsa,” his great grandson, Rogers, notes.

But 100 years later, Tulsa can still serve as a source of inspiration for Black business leaders like Chenault and Duckett, as well as Stradford’s own descendant, Rogers, who has built a business of a different kind: Today he heads one of the largest Black-owned financial firms in the country.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))