How colleges are preparing for a new public health threat: monkeypox

Lake Forest College in Lake Forest, Ill., is prepared to help students isolate if they test positive for monkeypox. (Courtesy of Lake Forest College)

Andrea Connor has become “the accidental COVID Czar” of Lake Forest College, a small school north of Chicago where she serves as dean of students.

“When COVID started, our crisis management team sort of multiplied,” she says.

Now, she’s relying on that same team to respond to a new health threat: monkeypox.

“There’s a lot of fear, a lot of concern,” Connor says. “So we want to educate people.” Her team is putting together guidance detailing monkeypox signs and symptoms, and what a student should do if they think they might be infected. Monkeypox is much less contagious than COVID-19, but Connor says it’s a school’s job to be prepared.

Ahead of the new school year, colleges across the country are repurposing the tools they developed during the pandemic to address the monkeypox outbreak, which the White House recently declared a public health emergency. It’s a different virus, with different risks, and colleges are having to adapt, says Dr. Lindsey Mortenson of the American College Health Association (ACHA).

“Many colleges and universities are thinking about ‘how do we turn the page institutionally?” Mortenson says. ” ‘How do we take all of these public health informed practices and apply them in a different context?’ ”

The risk of contracting monkeypox is low, but colleges are beginning to see cases

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the risk of contracting monkeypox in the U.S. is “believed to be low.” More than 7,000 cases have been confirmed in the U.S. as of Thursday, though experts say that number is likely higher due to testing limitations.

Monkeypox is most often associated with a rash that can appear anywhere on the body including the face, feet, hands, genitals and inside the mouth, the CDC says. But symptoms can also include fever, headaches and muscle aches.

The virus spreads through physical contact with the monkeypox rash, and the vast majority of people affected by the current outbreak appear to be catching it through sexual contact. Cases have been largely concentrated in the gay and queer community, primarily among men who have sex with men. But the CDC says sexual contact is not the only way the virus can spread. It’s possible for close face-to-face contact or indirect contact with the rash to result in transmission, though data show this is less common.

As a result, experts say, everyone should be paying attention to the virus.

“No outbreak stays limited to any one social network,” says Dr. Jay Varma, an epidemiologist at Weill Cornell Medical College. He adds that although the virus has been concentrated in the gay and queer community, “There’s no biological reason it couldn’t spill over into other groups.”

On college campuses, Varma says, areas to watch are those where students come into close physical contact with each other’s skin, including locker rooms, gyms or even theater groups.

The virus has already appeared on some college campuses. Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., University of Texas at Austin and West Chester University in Pennsylvania all told NPR they had at least one confirmed case over the summer.

At West Chester University, spokesperson Nancy Gainer says, “The student is in isolation and continues to do very well. There is a plan in place for them to finish their class remotely, and the student will not return to campus for the summer term.”

On July 28, the ACHA, which represents over 700 institutions of higher education, sent an email to its members with basic information about monkeypox, but more detailed guidance is still in progress, says Rachel Mack, director of communications at the ACHA. She says the ACHA is now coordinating with the CDC to schedule a webinar, and they’re also creating an FAQ document to share with members.

“All of this is in the early stages and we’re right now assembling a team of experts to help finalize the topics that are of primary importance to [institutions of higher education],” says Mack, in an email to NPR. “Our goal is to be responsive to the needs of our members and to meet those needs as quickly as we can.”

Monkeypox requires a longer isolation period than coronavirus

COVID-19 is usually contagious for less than 10 days, but a monkeypox infection can last a few weeks. That means a student who contracts the virus may need to isolate for a significant chunk of their semester.

“This presents a very important challenge for the individual, who has to put up with that level of isolation, as well as the university, which needs to make arrangements to support that,” Varma says.

One challenge is that most colleges have shifted back to in-person instruction after going fully remote in 2020. Schools told NPR they are still determining what remote learning will look like for students in isolation.

At the University of California, Irvine, where all classes are back in-person, students in isolation work directly with their faculty members to decide how to learn remotely, says David Souleles, who leads the school’s COVID-19 response team. “Instructors are encouraged to have a plan for such occurrences in advance,” he explains.

When it comes to where students with monkeypox would isolate, there’s huge variability across colleges, even in places where schools had housing set aside for students who tested positive for COVID.

“Some are retaining isolation housing for COVID, or for whatever infectious illnesses it may be needed for,” says Mortenson. “Others have completely relinquished their inventory.”

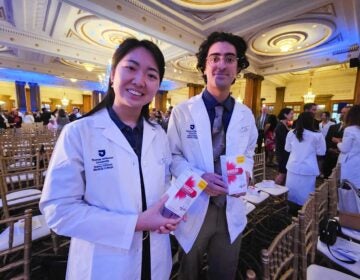

At Lake Forest College, Andrea Connor is working through housing logistics, and she says the school plans to help students isolate if they test positive for monkeypox. They’ll also help students meet basic needs including meals and laundry.

At West Chester University, which serves over 17,000 commuter and residential students, Gainer says the school is “committed to following CDC guidelines and having students [who test positive for monkeypox] self-isolate.”

In Ithaca, N.Y., at Cornell University, the campus health unit has published an online resource with information on monkeypox. The school is “developing testing, treatment and isolation protocols for those affected,” says Rebecca Valli, director of media relations. “We are also considering the potential academic impacts and accommodations which may arise.”

Students are concerned about monkeypox stigma

Because 99% of cases in the U.S. are related to male-to-male sexual contact, according to the WHO, there’s a growing concern about stigma and bias against the LGBTQ community.

That bias can have negative public health consequences if it prevents an infected person from seeking treatment and informing their close contacts about potential exposure, an important step in mitigating spread.

Student Liz Cortes, who co-leads the Queer and Trans Student Alliance at UT Austin, says they are frustrated by the ongoing stigma and is waiting to see if the university will address it. If the school fails to, “we would make it a priority to work with public health officials on providing accurate information and addressing misconceptions about the virus and our community,” Cortes tells NPR in an email.

UT Austin did not immediately respond to a request for comment about how it intends to address concerns about stigma. But the school’s health services website states that “anyone can get monkeypox, regardless of age or sex.”

Some universities are working with student groups to coordinate education and response efforts. At UC Irvine, Souleles says the school has convened a working group that includes representatives from the LGBT Resource Center. “We’re also consulting guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on reducing stigma in monkeypox communication,” he says.

Student privacy is another concern. At many larger schools, including UT Austin, University of Michigan and UC Irvine, health centers are equipped to test students for monkeypox. But other schools, including Lake Forest, don’t currently have the resources for testing.

Lake Forest students have to go off campus to get tested at one of five nearby labs, Andrea Connor says. One of those labs is an STI clinic, and if a student gets tested there, their insurance might bill it as a test for a sexually transmitted infection, even though monkeypox is not considered an STI, says Connor.

“Some members of our community wouldn’t want their parents to see that on their insurance,” Connor explains. “So there’s a lot of layers there.”

Still, Connor says she remains hopeful about the fall semester.