Derek Chauvin is sentenced to 22.5 years for George Floyd’s murder

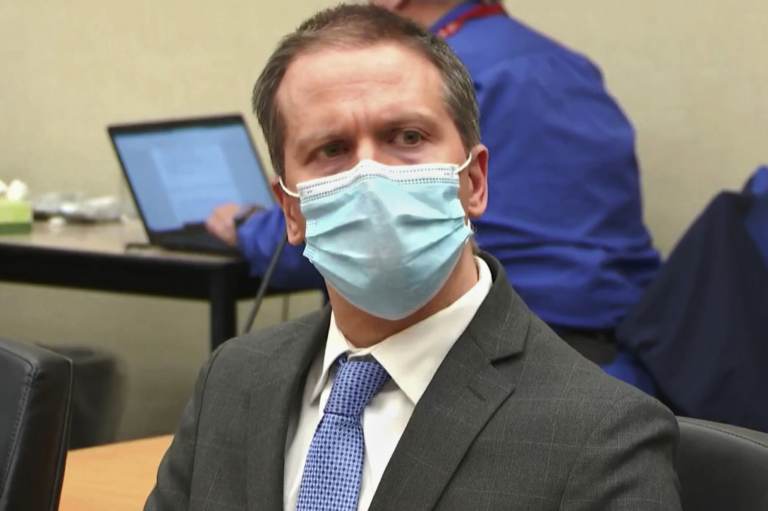

Former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin listens to verdicts at his trial in April for the 2020 death of George Floyd at the Hennepin County Courthouse in Minneapolis. Chauvin was convicted of murder and manslaughter charges in state court and is scheduled to be sentenced June 25. Court TV via AP

A Minnesota judge sentenced Derek Chauvin to 22.5 years in prison Friday for the murder of George Floyd — a punishment that exceeds the state’s minimum guidelines but falls short of prosecutors’ request of a 30-year sentence.

In April, a jury found the former Minneapolis police officer, who is white, guilty of murdering Floyd, who was Black, last year. The killing triggered massive protests against racial injustice and also prompted reviews of the police use of force — including how much the law should protect officers when someone dies in their custody.

As in earlier proceedings, the sentencing hearing was livestreamed from the courtroom. The sentence announcement followed emotional victim impact statements from Floyd’s family, as well as a heartfelt message of support from Chauvin’s mother.

Chauvin was seen on video pressing his knee onto Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds as Floyd lay facedown on the asphalt outside a convenience store with his hands cuffed behind his back. The police had been called to the store after Floyd allegedly used a counterfeit $20 bill to pay for cigarettes.

The guilty verdict against Chauvin was hailed as a civil rights victory. Since then, his prison sentence has been awaited as a possible affirmation of that victory.

Chauvin has been jailed since his guilty verdict. He was in court for Friday’s sentencing hearing, wearing a suit rather than a prisoner’s uniform by a special order of the court.

Chauvin offers condolences in a brief statement

Chauvin, who did not testify during his trial, addressed the court in remarks that he said would be kept brief as he is still facing other legal issues — including federal charges.

“I want to give my condolences to the Floyd family,” Chauvin said as he looked toward Floyd’s relatives in the courtroom.

And in a cryptic moment, the former officer added, “There’s going to be some other information in the future that would be of interest. And I hope things will give you some, some peace of mind. Thank you.”

Under Minnesota law, people sentenced to prison become eligible to be considered for parole after serving two-thirds of their sentence, as long as they’ve had no disciplinary problems while in custody.

Chauvin “is the first white officer in Minnesota to face prison time for the killing of a Black man,” according to member station Minnesota Public Radio.

Floyd’s daughter, 7, gives her victim impact statement

Floyd’s loved ones delivered four victim impact statements in court. The first was a video conversation with Floyd’s seven-year-old daughter, Gianna.

“I ask about him all the time,” she said, adding that she wants to know, “How did my dad get hurt?”

Gianna said her father is still with her in spirit. When she sees him again, she said, she wants to play with him.

“I miss you and I love you,” she said she would tell her father, adding that every night, he used to help her brush her teeth.

The girl added that other people have helped her father, after “those mean people did something to him.”

Floyd’s brother asks Chauvin: “Why?”

“This situation has really affected me and my family,” Floyd’s brother Terrence Floyd said.

Addressing Chauvin in the courtroom, Floyd said he has some questions.

“Why? What were you thinking? What was going through your head when you had your knee on my brother’s neck?”

He then took a moment to compose himself, after growing emotional.

He went on to describe how, in one of his last conversations with his brother, they had been planning playdates for their daughters.

Asking for a maximum penalty against Chauvin, Terrence Floyd said there should be “no more slaps on the wrist.”

Philonise Floyd, who has become an outspoken advocate for his brother after his death, then told the court that he has relived Floyd’s death repeatedly in the past year. He no longer knows what it feels like to get a full night’s sleep, he said.

“My family and I have been given a life sentence” to live without George Floyd, Philonise Floyd added.

Chauvin’s mother says she supports her son “100 percent”

Chauvin’s mother, Carolyn Pawlenty, spoke in court on his behalf and for her entire family, she said.

All their lives changed forever the day Floyd died, Pawlenty said.

Her son is not an “aggressive, heartless and uncaring person,” or a racist, she said. “My son is a good man,” Pawlenty said, noting his years of dedication to being a police officer.

Saying that she supports her son 100 percent, she added that the past year has taken a toll on him.

“When you sentence my son, you will also be sentencing me,” Pawlenty told Judge Peter Cahill. She noted that if her son serves a long prison term, his parents may not be alive when he is released.

Addressing Chauvin, Pawlenty said she is on his side and told him to be strong.

“Remember you are my favorite son,” she said.

Lawyers argued over aggravating factors

Minnesota guidelines called for Chauvin to be sentenced to around 12 1/2 years for second-degree unintentional murder, given his lack of prior criminal history. But state prosecutors pushed for a 30-year term, saying Chauvin “acted with particular cruelty,” among other aggravating factors in the case.

The prosecution also cited Chauvin’s abuse of a position of authority and Floyd’s killing in front of children and other witnesses, saying his punishment requires an “upward departure” from the guidelines. Cahill agreed, saying that aggravating factors had been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Eric Nelson, Chauvin’s defense attorney, asked for Chauvin to be sentenced to probation along with time already served, saying that Chauvin, 45, would likely be a target in prison. He also says that with the support of his family and friends, Chauvin still has the potential to be a positive influence on his community.

Chauvin was found guilty of unintentional second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter. But he’s being punished only for the most serious charge: second-degree murder while committing a felony. In Minnesota, a person convicted of multiple crimes that happened at the same time is typically only sentenced for the most severe charge.

The state’s maximum prison term for second-degree unintentional murder is 40 years, although the sentencing guidelines for second-degree unintentional murder largely taper off at 24 years.

Chauvin also faces federal charges

Weeks after Chauvin was found guilty of murdering Floyd, the Justice Department announced federal criminal charges against him and three of his fellow former officers over Floyd’s death.

A federal grand jury indicted the four on charges of violating Floyd’s civil rights, with Chauvin accused of using excessive force and ignoring the medical emergency that ended in Floyd’s death.

The other former officers — J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao — are also accused of not getting immediate medical help for Floyd, with Kueng and Thao facing an addition charge of failing to intervene and showing “deliberate indifference” to Floyd’s predicament.

The grand jury also indicted Chauvin over an arrest he made in 2017, in which he allegedly used a neck restraint and beat a teenager with a flashlight.

No trial date has been announced for the federal charges.

The three other former officers were already facing a state trial in August, on charges of aiding and abetting. But that trial has now been postponed until March of 2022.

All four of the Minneapolis officers involved in Floyd’s death were fired days after the incident.

Nelson had asked the state court for a new trial for Chauvin, saying intense press coverage tainted the jury pool. He also alleged prosecutorial misconduct, related to issues such as sharing evidence and handling witnesses. But Cahill denied Nelson’s motion on the eve of Friday’s sentencing.

Police killings rarely result in criminal charges

Floyd’s murder and other high-profile cases, such as the police killing of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky., have put intense scrutiny on the police use of deadly force against Black people, particularly by white officers.

An NPR investigation from early this year found that police officers in the U.S. shot and killed at least 135 unarmed Black men and women since 2015, and that at least 75% of the officers were white.

Law enforcement officers in the U.S. killed 1,099 people in 2019 — by far the most in any wealthy democracy in both raw numbers and per capita, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Those killings result in only a small number of officers being charged with a crime each year, and convictions of police on murder charges are very rare.

Last year brought a spike in the number of officers who died on duty, but as in most years, traffic incidents accounted for the largest share of those deaths.

Chauvin case propelled calls to change policing in the U.S.

The uproar over Floyd’s death has helped change how some police departments train officers to use force, particularly chokeholds or carotid restraint holds.

But as NPR reported last summer, bans on neck restraints have been mostly ineffective or unenforced. Chauvin’s actions against Floyd, for instance, were described by Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo as violating the department’s policies on the use of force, as well de-escalation and rendering aid.

Advocates of police reform also say it’s time to limit or revoke qualified immunity — a legal doctrine established by the Supreme Court in 1967 that has been used to shield officers from facing liability for egregious actions while on-duty.

“The people pushing for this change say the Supreme Court has tightened qualified immunity so much in recent decades that it’s become nearly impossible for courts to recognize even blatant examples of police misconduct as illegal,” NPR’s Martin Kaste reported last year. “But police see things very differently. For them, qualified immunity has become a necessary safe harbor in a fast-paced, often dangerous job.”

Qualified immunity’s critics range from far-left activists to the libertarian Cato Institute.

A federal judge joined the critics last year, saying that while an officer in a case before him was protected by the doctrine, qualified immunity should be tossed into “the dustbin of history.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))