You shouldn't be here: The story of Jovan Weaver and Wister Elementary School — part one

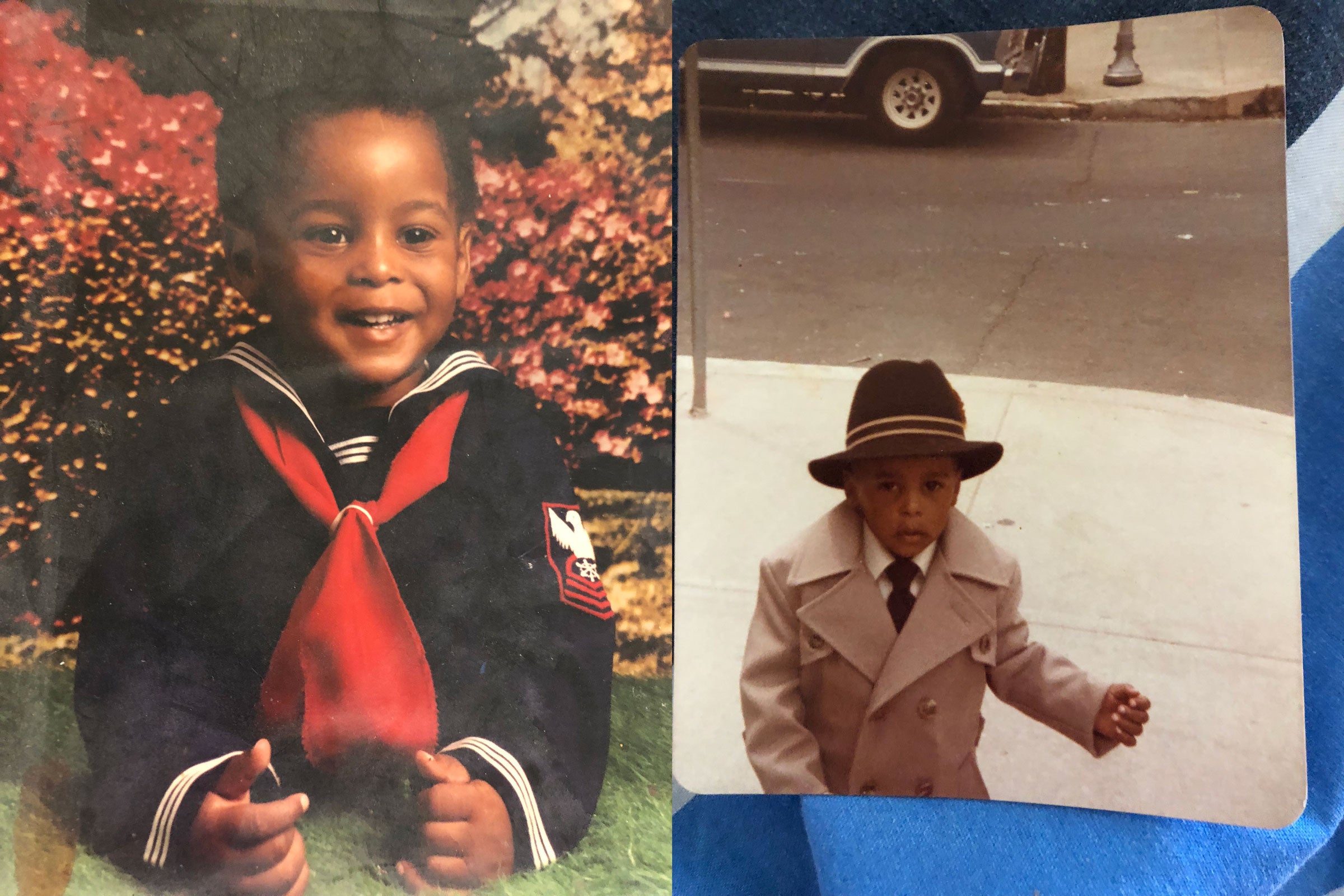

Principal Jovan Weaver knows well the trauma that many of his students experience. We hear his struggle to overcome a tumultuous childhood.

Jovan Weaver has a story to tell.

It’s August 2016, and two young children have just been hit by stray bullets during different gunfights in Philadelphia in less than a week.

“About a week ago, there was a six-year-old girl shot. There was also a six-year-old boy shot,” said Jovan.

Jovan had just become the first-time principal of John Wister Elementary, a school serving a mostly poor student body in East Germantown — the neighborhood where the second shooting took place.

This hammered home one of the big reasons he has dedicated his life to education.

“The importance to instill sound values into our children, conflict resolution, things that this community is struggling with at this point,” he said.

This was about a week before Wister Elementary was set to re-open after the summer break. And Jovan stood in an empty classroom thinking of how he’d address his faculty as a principal for the first time.

As he contemplated what to say, he couldn’t help but think of those two children — how vulnerable they were, and how much of himself he saw reflected in not just them, but all the kids who would soon fill the school.

“I am these students,” he said. “And I need them to see me inside of every single student that walks through this door — that hope, that possibility, that option of success.”

Jovan’s 34 and African American, and as he began to speak to the faculty, he paced the room nervously, with dozens of teachers and support staffers listening intently.

“I really thought hard and long about how I wanted to start this morning, and I was encouraged by a few people in this room to share a story about a young man that I know very well,” he said.

He talked about a young man who had endured trauma, neglect and abuse as a child growing up poor in Philadelphia during the crack-cocaine epidemic. The young man never met his father. And the young man’s mother, Jovan explained, often went out partying.

“The result of her partying led to her coming home one night with her girlfriends, and he vividly recalls his mother giving him a joint to smoke. He was five years old at the time,” said Jovan. “So, she continued down this downward spiral of drug abuse, continued to party, and all he could really think of was getting away.”

The young man, of course, was Jovan Weaver himself.

And the story of how he got away — went from potential casualty of the streets to principal of one of city’s most needy and controversial elementary schools — is one he’s often shied away from telling, one he’s often repressed, one that’s sometimes easier to deal with by putting in the third person.

“I try often not to think about it,” he said later in an interview. “But if I step outside of myself — and, you know, listen to myself — I will be like, ‘Holy shit. You shouldn’t be here.’”

The story of Jovan Weaver and Wister Elementary can also be experienced as a radio documentary. The tale is told across the four-episode second season of our podcast “Schooled.” It’s based on more than two years of reporting about the students, the parents, the faculty, and the huge political fight that sprung from Wister Elementary. You can listen by using the play button above.

Part One: You Shouldn’t Be Here

In August 2016, when Jovan Weaver was thinking of the students who would soon enter Wister Elementary, it was hard for him not to think of one of his own boyhood schools — Blaine Elementary, which he attended in the early 1990s.

“This whole stretch, I’m talking drug dealers galore,” he said, walking around the Blaine schoolyard recently. “Just crack pipes and vials and you name it.”

Blaine is in Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion neighborhood, a poor section of the city that was especially ravaged by crack. When we visited, Jovan hadn’t been back to his old neighborhood in decades. And it was an unnerving experience.

“I knew as a child, this was not the place you wanted to hang out,” he said. “You’d literally see just crackheads everywhere, abandoned homes everywhere.”

Jovan lived here for a few years in a rowhome on a street barely wide enough to fit a car.

And as we walked closer to his old home, Jovan turned his shoulder to it, literally not wanting to bring himself to face it.

“A lot of nightmares came from that place,” he said. “I would rather not go in there. The level of abuse, the level of neglect, forget about it, man. Forget about it.”

Jovan was born in January 1982. His mother, Robin Weaver, was 17. She’d been dating a man who already had a couple of kids with another woman.

“He was like one of my crushes over the summer,” she said.

When Jovan was born, it was made abundantly clear that his father wouldn’t be involved.

“There was an argument, ‘That ain’t my child — this, that and the third,’ and everything. It was just a mess. It was hard for me. I cried a lot. I was like, ‘That’s not right.’”

It also became clear that Robin was far from ready to be a mother. After finishing high school, she asked her mom to take responsibility for her newborn. She was thinking of joining the military.

“I asked her if she would take care of him while I would be gone. ‘That’s your son. You’re here to take care of him.’ So, I turned around and said to her, “Well you left me with my grandmom while you went to Atlantic City to work. And then on top of that, you winded up pregnant with my brother.’ Oh, she didn’t like that. But we were in the street arguing. I said, ‘So, what’s the difference?’”

From there, Robin’s behavior became more and more destructive.

“So I’m, like, ‘‘eff’ it. She don’t care, I don’t care’ — hanging with the wrong people, you know. That’s the mentality I had back then. It just seemed like my mom didn’t understand at the time. So, I went from drinking beer, drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana and stuff and snorting, and then just doing coke.”

Despite the dysfunction, Jovan started showing signs that he was developing very well intellectually.

“When he was three years old, we would take the wooden puzzles, three of them, turn them upside down, and then say, ‘Alright, Jovan, it’s time to put the puzzles together,’ and we’d time him. It will be like three seconds or something like that. And we’re, like, ‘Oh my God.’ And I said, ‘I told y’all. I told y’all.’”

Jovan remembers his grandmother as his only source of stability in those years. The two of them would ride the bus together, often talking in terms of math, comparing prices of things to when she was younger.

When he talks about her now, he chokes up easily.

“Those are just rich memories from my childhood that I have, because she was one person who I truly loved and looked up to,” he said.

By the time his mother was 22, she had three more children with another man who was also quickly out of the picture. The family was living in another poor section of the city — getting by month to month on food stamps and welfare. Robin’s drug habit got out of control, though, and they soon they lost their apartment.

“One night, my mom woke us up. We had to pack our bags. We end up getting on the bus, and we ended up down at the Salvation Army.”

They bounced between a few emergency shelters before settling into something more long-term. All the transition was chaotic for Jovan, including being pulled from his school at the time, Charles Drew Elementary.

“You don’t know what’s going on. You don’t know why you’re leaving. One minute I’m going to Charles Drew, the next minute I’m not in school. I don’t know what’s happening,” he said. “And you’re just confused. You literally don’t know where you’re going to stay, you know? I remember the food. I remember the cots.”

It took a while, but eventually, the family was able to settle into their own place again. And so it was when Jovan was eight years old, that they moved into a three bedroom rowhome on that narrow street in Strawberry Mansion.

‘All out war’

Not long after Robin and her four kids moved into the neighborhood, she began dating a crack dealer.

“We were boyfriend and girlfriend, and I know him and Jovan couldn’t get along at all,” said Robin.

“He physically abused her. I hated his guts,” said Jovan. “I hated his guts. He loved my little brother. I hated that too.”

For Jovan, these memories are still vivid, and painful.

“You would see your mom hurt. You would see your mom get hit. And it enrages you. But you can’t do anything, you know, as a child, you got this man overpowering you, and you’re super weak,” he said. “So you just gotta take it.”

The boyfriend spent most nights at the house, and he and Robin used it as a headquarters for their crack operation. Her mother lived with them as well, but was often bedridden at that point, saddled with glaucoma and diabetes.

“I would have to sleep downstairs,” said Robin, “me and my friend, because people would come and knock on the door and want to buy some stuff.”

Jovan remembers being in the bedroom he shared with his younger siblings, listening through the floorboards to the action happening downstairs.

“You are fully aware that there’s a lot of activity going on,” he said. “You don’t know what the activity is. Sometimes you can sneak out and try to peek.”

Robin thought, or at least told herself, that her kids were too young to understand.

“‘My kids don’t know what’s going on,’” she said. “That’s what I said.”

Just walking through the house, Jovan would sometimes find drugs in plain sight.

“I mean just plastic bags full of just crack,” he said.

It was a cutthroat, often violent world and Jovan’s house was right in the middle of it.

“It was an all out war,” said Robin. “You sitting on the steps, [there’s a] shooting and they busting glass windows out of cars, and I’m like, ‘What the…?’ Oh my god. Ugly. Girls fighting over guys with bats or whatever the case may be. You got one neighborhood coming into the next neighborhood, like, ‘What in the world?’”

During the three years that the Weavers lived there, city records show that nearly 200 people were killed in their section of the city. Eleven of the homicides occurred in the streets immediately surrounding their house.

“This guy got shot,” said Robin. “When I went to the scene, his brains were inside his hat on the ground.”

Jovan can still hear the police sirens and gunshots in his head.

“You see a person one day; you don’t see a person the next day,” he said. “You see people grieving. As a child you kind of don’t understand a lot of it unless you’re, like, you know, watching a movie, and now you’re making a connection with some of the things you’ve seen in the movie or seen somewhere else, ‘Wow, this is what they’re talking about.’”

Growing up in this setting created a distorted view of the world for Jovan.

He hated life inside the house, and as a nine year old, often ran away — crisscrossing the city on his own to get to relatives’ homes on the other side of town.

But at the same time, immersed in the culture of the neighborhood, he couldn’t help but be attracted to parts of it. When we walked around his old schoolyard recently, he was struck by some of the feelings being stirred up. He remembers being with friends and watching some of the local drug dealers play basketball, them betting with each other on the games, surrounded by crack vials.

“It’s stuff that kind of fascinated you as a child, you know? Also [we’re] hyper-aware that these guys are the reason that our playground looked this way, but yet we’re fascinated by this somehow. How ironic is that? How weird is that? I’m having flashbacks right now of me, like, ‘Wow, I want to be like that person,’ or, ‘I want to shoot like him,’ or, ‘I can do that,’ Like, no, that’s unbelievable to me….But again when that’s your environment, when you don’t really know anything different, then that’s what you’re going to aspire to be. And it’s so sad. It really is.”

Despite the chaos around him, Jovan’s early knack for academics stayed with him. And Blaine elementary became his one true refuge, a place where he felt celebrated and encouraged.

“Home was a fearful place. I didn’t trust being at home. I didn’t trust anything that was happening there. So I would run away,” he said. “I would go to school and I would have that exact opposite feeling, because I did trust my teachers, and I felt like I was in a good place, and I was able to smile and laugh and have friends.”

One teacher at Blaine, Sandra Ford, saw something special in Jovan, and pushed to have him accepted to another public school in a middle-class section of the city.

So instead of going to Strawberry Mansion Junior High for 6th grade, he began catching a bus at 6 a.m. to Austin-Meehan Middle School in Northeast Philadelphia. It was a form of public school choice before the term was widespread.

True pain

But then, in 1992, when Jovan was ten years old, something happened that forever changed him. It was late fall. He was in sixth grade. And his mother sat him down to tell him she was leaving.

“It didn’t really register too much for me at that time, because she would go out for Friday, Saturday and come back Sunday night. ‘OK. Whatever,’ like, you know, it was no big deal,” he said. “But that was, you know, she never came back after that.”

Jovan’s grandmother was still there, but with her being so sick, it was almost like the kids were left completely alone. Jovan’s next oldest brother was seven. His twin brother and sister were five.

“We were just basically alone. I remember lights being out. I remember having $7 you know, trying to find change in couches and rack up pennies and stuff.”

For the next two weeks, Jovan was more or less in charge of his younger siblings, getting them to school, figuring out what they could eat.

“My brother would share stories about how he would eat just dry packs of ramen noodles, just to kind of sneak because we didn’t have anything. And, I think, you know, my grandmom finally got it together, and basically called the authorities and called family, like, ‘I don’t know where she is. She’s not here.’”

Jovan’s brother and younger sisters went to live with their father and his family, who weren’t related to Jovan. That left care for the 10 year old a huge question mark.

“I was just like kind of out there, like, what’s going to happen with Jovan? Who’s taking Jovan?”

Confused and abandoned, he got angry. He felt completely isolated. When he’d hear the word love, it made him cringe.

“Because you don’t feel it at all,” he said. “All you feel is true pain and you don’t understand why.”

From week to week, Jovan again didn’t know where he’d sleep — getting passed from one family member to another. Ultimately, one of his older cousins offered to take him in.

But this wasn’t really a parent/child arrangement. And as Jovan got slightly older, the cousin expected him to help her pay the bills. At age 12, he started working in a clothing store, stocking shelves off the books, learning a strict work ethic.

But at the same time, his cousin was only nine years older, living a life far from ideal for a child.

“I’m twelve years old emulating everything that I’m seeing everyone else doing, because I feel like that’s what I should be doing. So I’m twelve years old and I’m smoking cigarettes. I’m twelve years old and I’m losing my virginity. I’m twelve years old and I’m doing all of these things I shouldn’t be doing. I’m thirteen years old and I’m drinking Old English. But that’s was my environment. That’s what I was around,” he said. “Looking back, I’m like, ‘No one said, ‘This is not cool.’ No one said, ‘Maybe you should stop’ or say like, ‘Why don’t you focus on this.” No. They egged it on.”

During this whole time, Jovan’s still had no idea where his mother was, and he convinced himself that she was dead.

At that point, it was almost harder to learn that she wasn’t. His cousin was the one to break the news.

“I was, like, ‘What do you mean you found my mom? Where is she?…What was she doing?’ ‘Well, she was on drugs.’ And I almost lost it, like, ‘What? You chose drugs over your kids? You chose maybe a man over your kids?’ I had no idea where the hell she was during those two years, what the hell she did. I really didn’t want anything to do with her.”

Talking about that time now, Robin says she simply wasn’t strong.

“I just left, you know, still trying to get my head together and everything and stuff, but there wasn’t like one day that I never thought about my kids,” she said. “And the only thing I kept saying was, ‘Well they’re with family. They’re doing good,’ and all along they wasn’t. And I never knew that. And how they say, ‘Family will fuck you first’ — that’s what happened.”

Jovan and his mom began to talk again. She wanted him to go with her to a friend’s wedding, and they made plans to go to the movies. But when the day came, Robin didn’t show up, didn’t call, and Jovan never heard about the wedding again.

“And at that point I was done,” said Jovan. “Like, I don’t want anything to do with you right now. I actually tried to give you a chance again, despite how mad I was. Like, ‘You’re my mom. I love you. I was trying to give you chance, but you just fall off the face of the earth again? I have no way to get in contact with you? So I guess you relapsed?’ I have no idea.”

‘A fine line’

In 1995, Jovan enrolled in Abraham Lincoln High, another school in Northeast Philadelphia far from his home on the other side of the city. But by the time he got there, he could have been well on his way to becoming another statistic of the streets: A dropout. A convict. A chalk outline on the sidewalk.

“I’m, you know, hanging in crack houses and have no idea where my life is headed because everyone I see — the same things are happening to them,” he said. “So, is this really life? Is this all that life is going to offer me right now? That’s truly, like, you didn’t see people living long. And if they were older, they weren’t in a good position.”

But Jovan’s story did not take take that turn. What happened?

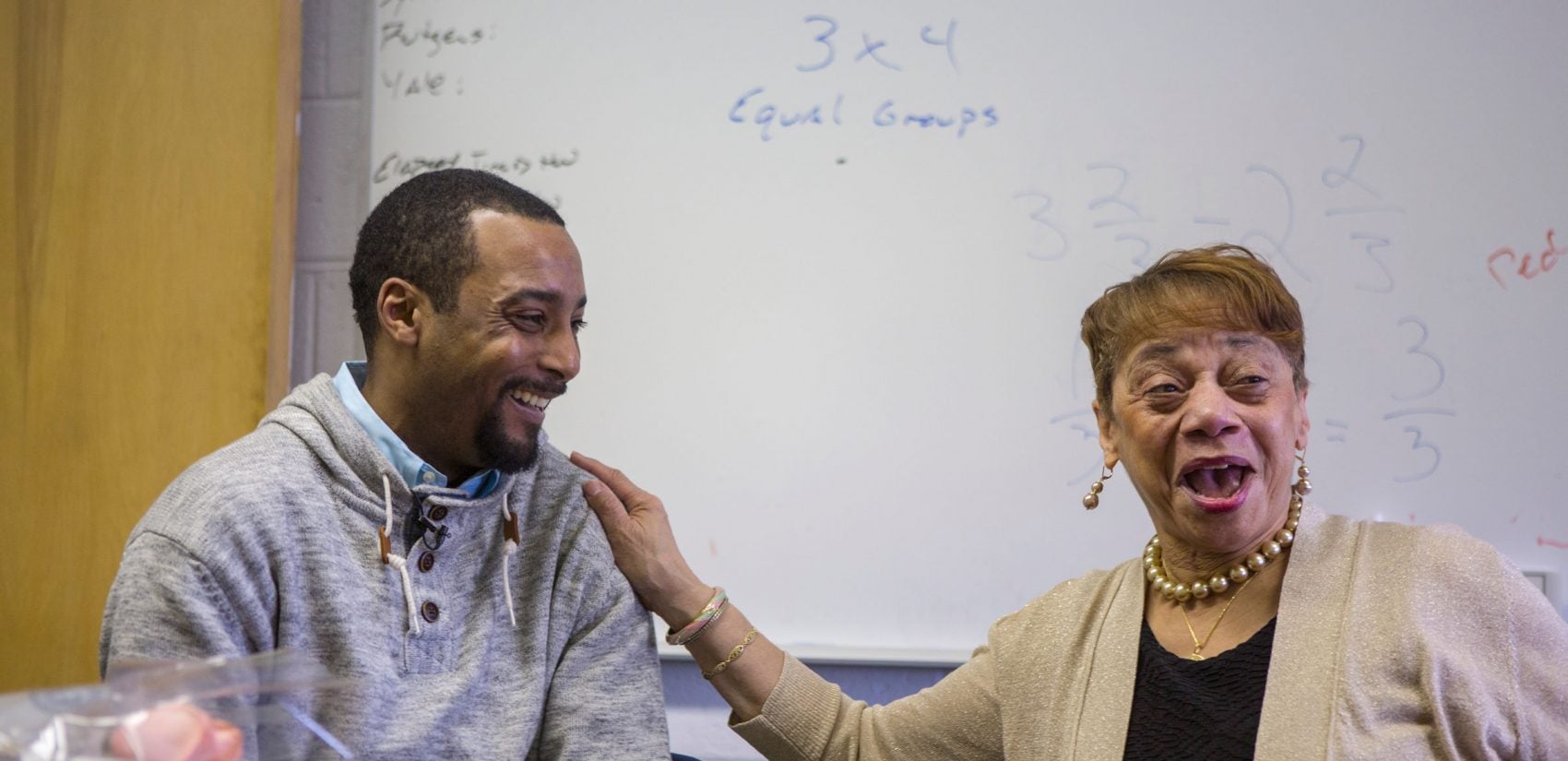

For one, Ms. Marie Brown happened.

Marie Brown was Jovan’s geometry teacher at Lincoln High, and recently, Jovan met with her to talk about his past and present.

As they greeted one another with a big hug, Jovan offered her a bouquet of pink roses, and beamed with joy. Immediately, they began reminiscing about the old days.

“Jovan was one of the best math students I ever had, and always a gentleman — when he came to school,” Brown said, with a big laugh.

When Jovan started at Lincoln, despite his intellectual gifts, school was not a priority. And living with his cousin made it easy for him to cut.

By sophomore year, with Brown’s geometry class on his roster, he got into the habit of skipping more days a week than he’d show up. He was skipping partly because he felt work was more of a priority, and partly because it seemed nobody really cared if he went to school anyway.

But, still, when he did go, he did well.

“He understood what was going on in the classroom. He’s able to master the task, but he wasn’t there,” said Brown. “So why aren’t you here? What are you doing? What is keeping you away from us? And you belong here. So I had to delve into that.”

Brown, long retired, still knows how to run a room. She’s stylish, with a quick wit, a skeptical eyebrow, and little patience for suffering fools.

Being an African-American teacher in a school in a largely white neighborhood, Brown felt a special obligation to the students of color in the school. It’s something she was told by the man who first hired her — and one of the reasons she also became the school’s disciplinarian.

“I was there to save our kids,” she said. “And I feel there was a certain element on that staff that looked at black kids as trouble. And I just felt that I needed to save them, and that was because that’s what that man told me: ‘Those kids need you.’ And it just resonates in my head all the time now. ‘They need you,’ you know, and I’m there. I’m right in to see what’s going on.”

The moment that really forged the relationship between Jovan and Brown came after he got into a fight. It happened on the way to school in the morning, but authorities were alerted, and later in the school day Jovan was taken out of a classroom in handcuffs.

It was the second time in six months that he had been arrested. The first was for loitering.

Before being taken out of the school, Jovan was put in Brown’s office.

“She came in and said, ‘What the hell are you doing? I’m going to try my best, you know, because your influence and everything that you’re around is pulling you over to this, like, dark side. And I will try my best to pull you over to the good side.’” Jovan remembers her saying. “And she’s, like, ‘It’s a fine line.’”

Jovan wasn’t charged with a crime, but he was booked into the local police precinct. He couldn’t leave until a family member came to pick him up, and as he sat for hours waiting, something about Brown’s words stuck with him.

“It was really that moment,” he said, “sitting in, like, a little holding cell, being fifteen years old, like, ‘What the hell am I doing?’”

When he came back to school the next day something was different. Through Brown, he felt connected in a way that he hadn’t before.

“She cared. That’s it. There was not many people who took the time, who really took the time. I was absent for all of my teachers…and she was the one who pulled me aside.”

For Brown, this was the purpose of her job: making relationships with students who may otherwise have fallen through the cracks. And in this way she says she stood out from many of her colleagues.

“They’re only interested in the students that do well. They’re not interested in students who seem to cause problems, or who seem to be a problem, or seem to lack interest in school,” she said. “They want everybody to be the good student. No, you’ve got to develop that child into becoming a good student. That’s your role. That’s your job.”

With Jovan, Brown made quick work of that task. Clearly he had the talent. It was just about showing him attention and getting him to see that he could become a better version of himself.

“You have this traumatized young man who was screaming out and yelling for someone to reach out to him,” Jovan said. “And in the meantime just absorbing so much and conforming to his surroundings. But then the first person who showed an interest had such an impact. And that’s part of my story.”

One of the biggest things Brown did was help Jovan make connections to a more positive set of role models and peers. She got him an interview for an intense, year-round program at Temple University that helps Philadelphia public school kids prepare for college.

“My first official interview was really scary. It’s like a panel of people, and I’m, like, this guy who was just in a holding cell a month, six weeks prior. And now I’m sitting in this interview at Temple University…like, ‘What?’”

Jovan was accepted, and all of the sudden he had access to a different world.

In truth, he was still drinking, smoking weed and partying with the older crowd. But it was as if blinders were coming off. He slowly began to see parts of life he didn’t know were there.

“Almost like a springboard for change for me,” he said.

Jovan was encouraged to work on a submission for a major, citywide science fair. And he found he loved the work. He poured so much of himself into it that he won first prize in one of the categories using his math skills.

But the victory was bittersweet, revealing in stark relief how truly alone he was.

“No one thought that I could do it. And to hear your name called ‘first place’ when so many people doubt you, and you don’t really have anyone. And so I’m happy and I feel great, and then I look around and all I see are like, you know, my friends or my peers with their parents, and I have to go back and I’d just sit in the seat,” Jovan said, choking back tears. “And it was always just a hole, because I never had that.”

Giant steps

Despite lacking that family support system, by senior year, Jovan positioned himself well for college. And he was accepted to Penn State University’s Main Campus.

“That’s a giant step for an inner-city kid,” said Brown, “a real giant step because in most cases they try to put [students from Lincoln] in the area campuses. So you know he had some real potential.”

College, though, was a steep learning curve for Jovan.

“I had to, like, work my ass off. I had to teach myself study habits. I had to develop like all of these things that I wasn’t necessarily prepared for because my natural gifts and talents weren’t necessarily holding up.”

Jovan became driven to succeed, burying himself in the work. He was determined to get a degree in business and become an accountant. There were social barriers, too, that he also figured out how to overcome.

“I’m like, ‘Your dad is a multimillionaire, and I don’t know my dad, but we’re here…” he said. “We’re all people. We’re all human. So that was just an invaluable experience.”

While Jovan was away, Robin began a slow path back to sobriety and self-dependence. Now, she’s a nursing assistant. Part of getting there included a stint in a recovery home.

“And it was like this, everybody’s sitting, ‘Ok, today. You got Oodles of Noodles for the whole time that you’re staying here,’” Robin said, mimicking the counselor, pounding her fist on the table. “So somebody said, ‘Why?’ ‘Isn’t that what your children ate, when you were out there?’ And I was like, ‘Oh, shit.’”

During this time Jovan and his mother still had minimal contact. And when they did talk, the past was almost taboo.

“I didn’t want to like, ‘Oh, I went through this and I went through that,’ because I’m quite sure my kids didn’t want to hear that, because they wanted their mom,” said Robin.

There were moments during college when Jovan was unsure if he’d actually make it through. He had to take some time off and fell out of step with the graduating class he began with. Early on, he did have his grandmother to rely on, but she died when he was an underclassman. After that, without any real support from family, he persisted.

And in December 2004, he walked down the aisle in cap and gown. But, again, no one from his family was there to cheer him on.

“That actually hurt to be honest with you,” he said, “because it was, like, ‘Wow, you’ve missed so much.’”

Soon after, on New Year’s Eve, Robin called and opened up in a way she hadn’t before.

“She apologized and basically was saying there’s nothing that she can say to justify anything that she did,” said Jovan.

“The only thing I could tell my kids was that I was sorry,” Robin said. “And I’m here now. We’ve got to make it better and we’ve got to move on.”

“I’m just like, ‘There’s nothing this lady can say to me right now that’s going to make me feel any better.’ So I got to let it go,” Jovan said. ‘“I forgive you. I just want you to know that.’ And then we moved on ever since then, and it’s just like a cordial friendship.”

He then corrected himself.

“I probably wouldn’t even say ‘friendship’ unfortunately, but it’s a cordial relationship.”

“You still think about it now and then,” Robin said. “Maybe what I did when I was younger, I shouldn’t have did what I did, and I wouldn’t have that tragedy happen to me.”

“But she feels it,” Jovan said. “She called me a couple of years ago just crying. Just crying and apologizing again for everything that she did. But what that showed me is, you know, bad choices eat you up. And it’s still eating her up.”

Pouring out

After college, Jovan married his high school girlfriend and became an accountant. They had a child and Jovan was happy to be providing his daughter with the comfortable middle-class life he’d never known.

“I’ve always had a model of what I did not want to do, did not want to become,” he said. “And I told myself early that if I was fortunate enough to have kids that they would never have the experience that I had. Period.”

But the more he thought about where he’d come from, and who he felt he was meant to be, and the more he thought of the important people in his life — people like Ms. Brown — the more he felt unsatisfied in his work.

His wife, who was a teacher, told him he would be great with kids — and she also showed him some of the testing data for Philadelphia public schools.

“I was like, ‘Wait, you serious? Like, kids can’t be failing this bad on this?’ So that was a great seed for me,” Jovan said. “And I’m like, ‘All right, let me just try it.’”

He interviewed with Mastery Charter Schools, willing to take a pay cut. And a few weeks later he found himself teaching algebra to ninth graders. He got an emergency teaching certificate, but after a year, still wasn’t convinced the classroom was his calling.

He stayed for a second year, though, and that’s when things really started to click.

“They knew when they were walking into Mr. Weaver’s class there was going to be some serious learning,” he said. “And from day one we rocked out.”

Since then, he and his wife had another child, and within seven years Jovan moved up the ladder within Mastery from teacher to master teacher to assistant principal to principal of Wister Elementary.

And there, in August 2016, he stood before his teachers for the first time, telling that story about a young man.

“And this young man is now standing before you as a principal of Mastery Charter School at John Wister Elementary,” said Jovan, his teachers roaring in applause.

Jovan wasn’t afraid to share his story — making himself extremely vulnerable in front of his new staff — because he hoped to shape a mindset among the faculty: This work is real. This work is urgent. And all children have tremendous opportunity within them.

But his decision also speaks to who Jovan Weaver is as a man — someone devoted to being an instrument of change.

“I truly feel like my life is not for me. It’s for others and for people to draw from it, draw strength from it,” he said. “I feel like I have so much love inside of me I just want to pour it out. And I want other people to know what that feels like.”

But Wister was no ordinary principal job. Jovan was taking on one of the hardest challenges in all of public education. With a faculty brand new to the school, he was expected to vastly improve outcomes for a student body besieged by deep poverty.

And he had to do it under a microscope. Through much of the prior year, Wister found itself at the center of a hostile debate when the School District of Philadelphia proposed turning it and two other schools over to charter organizations.

And in the end, after it was decided that Mastery — the biggest charter organization in the city — would take over, it was Jovan’s responsibility to deliver, with many people ready to make hay over either his success or his failure.

“You just feel a heavy burden to succeed. You feel the heavy burden to serve this community. You feel a heavy burden to serve these kids,” said Jovan. “You just feel a lot of pressure.”

—

Continue reading in part 2

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.