The Science of Schooling — Episode Transcript

On this episode, what research can tell us about the way we educate, and how science informs this process — or doesn’t.

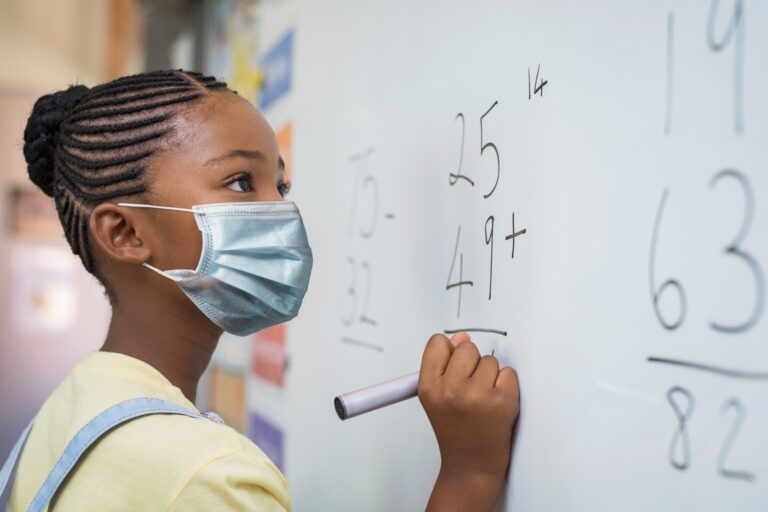

(Rido81/Big Stock)

Subscribe to The Pulse

INTRO:

Maiken Scott: This is The Pulse – stories about the people and places at the heart of health and science. I’m Maiken Scott.

When kids start school – it’s like they’re learning to crack a new code.

[KIDS VOICES]

Letters that represent sounds and create words.

[KIDS]

Those letters unlock books and stories.

[KIDS]

Numbers that describe amounts, that you can add and subtract.

[KIDS]

Or you can use them to figure things out.

[KIDS]

Geography, social studies, history.

[KIDS]

Science.

[KIDS]

New lessons every day, new skills going into young brains.

In many ways, the basic structure of school looks the same now as it did when I was a kid, when my parents or even grandparents were kids. The classrooms, the desks, the blackboard, the way teachers deliver lessons — it’s a system that evolved over many, many decades — and some things just became status quo.

But – with the pandemic — a lot of education had to change in a short amount of time – in some cases, basically overnight. And while that’s been hugely disruptive, it’s given us an opportunity to ask some questions – or to wonder out loud. Why are we doing things this way? Does it actually make sense, given what researchers now know about the brain, and how we process information?

On today’s episode: what research can tell us about education. How science informs the process — or doesn’t.

SEGMENT 1:

Here to get us started now is Avi Wolfman Arent — he’s WHYY’s education reporter.

MS: Hey Avi.

Avi Wolfman-Arent: Hey, Maiken, how’re you doing?

MS: Good.

AWA: Okay, so I want to start with a question for you, which is did you attend kindergarten?

MS: I did but I attended kindergarten in Germany and it’s a totally different thing. So it starts when you are about three years old usually, and it goes all the way until first grade. So I attended kindergarten for like three years.

AWA: Okay, that’s definitely different.

MS: Yes, and we do nothing but play in kindergarten, at least when I was a kid. We did a lot of crafts, and playing in a circle, and like clapping and singing.

AWA: Sounds great.

MS: Yeah! Playing like these orff instruments that are kind of like marimbas and I remember a ton of origami. That’s all skills I still have with me, I’m folding boats all the time still to this day. But that’s what I remember from kindergarten. How about you?

AWA: I did go to kindergarten, it was not like that. I really don’t have a lot of strong memories of kindergarten at Takoma Park Elementary School in Takoma Park, Maryland. It was a half-day kindergarten. I believe I was in the morning session, and my main takeaway really from the whole year is that the first friend I made was a kid named Owen, and we are still friends to this day.

MS: I love that. I still have a friend from kindergarten to his name is Philip. So, but in the US kids in “kindergarten,” you do writing, you do math, right? It feels a lot more like school.

AWA: Absolutely. For a lot of people, kindergarten is where you get started on the fundamentals of academic education. But with the pandemic, there are more parents who seem to be not enrolling their kids in kindergarten right now. We don’t have definitive national numbers yet, but the head counts for example in Pennsylvania and a lot of other states show big dips in kindergarten enrollment. And it makes sense because kindergarten’s not mandatory in most states, and a lot of parents just don’t see the point of sending their kids to school in this uncertain year, where they may be in person and may be virtual — you know you don’t quite know week to week.

MS: Yeah, I mean I’m imagining a kindergartener doing online school or some kind of mixed mixed model, and it just seems more hassle than what it might be worth.

AWA: Absolutely, absolutely. And so it raises this larger question like, why do we in America have kindergarten in the first place? You know, all the other grades are in elementary school, or at least are a number. So what is kindergarten? Why does this thing exist? Why does it start around age five? Like, what is this thing? So I started looking into it, and to help tell the story I do need to borrow your German actually for a second. Can you read this name for me?

MS: Alright, Friedrich Froebel.

[LAUGHTER]

AWA: Friedrich Froebel.

MS: Yeah, it’s a hard one, I’m sorry Avi. So Friedrich Froebel.

AWA: Friedrich Froebel.

MS: Good enough.

AWA: Okay, so the idea of kindergarten starts with this guy, Froebel, who is living in Prussia — modern day Germany — in the early to mid 1800s, and he has a revolutionary idea. And that’s that kids learn through self discovery and play. The teacher doesn’t drill knowledge into children, they kind of create the conditions for kids to teach themselves.

Jennifer Lin Russell: It was a very distinctive educational model. Focused on promoting young children’s spiritual and moral development.

AWA: That’s Jennifer Lin Russell from the University of Pittsburgh – she studies education policy and helped me understand the history here.

In 1837 Froebel establishes the first kindergarten — which translates to “garden of children.” Is that right?

MS: That is right, but it could also translate to garden for children.

AWA: Okay, garden for children — so the first kindergartens are totally independent. They’re not part of any larger school system.

It’s almost like a schedule or a sequence. You started the day with songs, and then after songs, Froebel said children should move on to playing, and so on. And this concept migrated to America along with German immigrants. The first kindergarten opened in a place called Watertown, Wisconsin in 1856.

JLR: And once they were in the U.S. among the German community they caught the attention of progressive education reformers.

AWA: Including a woman named Elizabeth Peabody, who formed America’s first English-speaking kindergarten in Boston in 1860.

JLR: This group of kindergarten pioneers — it was really almost like a social movement — promoted kindergarten as a distinct form from traditional schooling with this focus on play, flexible physical environments, lots of outside activities, and very deliberately the exclusion of traditional academic subjects.

AWA: At the time that kindergarten first started — this is the early industrial revolution — children, even this young, are often just seen as laborers or potential laborers. And the progressive reformers wanted to change that.

JLR: This was partly with the transition of thinking of young childhood as this special, protected time.

AWA: And so kindergartens start to spread, but the reformers weren’t satisfied

JLR: These pioneers realized that in order to really get traction and make this happen, the way to do it was to link them to elementary schools.

AWA: And so kindergarten just got tacked onto the bottom of the elementary school ladder. And over time, kindergarten started to look and feel more like school – like any other grade. Some of this was just organic — based on the fact that they are all in the same building now, being run by the same people.

But there was also outside pressure to make kindergarten more academic. Some of it stemmed from global affairs.

JLR: The kind of Sputnik-era need to accelerate a student’s academic achievement…

[BACKGROUND AUDIO]

AWA: And some of it stemmed from the rise of new exams designed to hold schools accountable. If you’re gonna judge a school based on how third-graders perform on a standardized reading test for instance, the obvious move is to start ‘em early.

JLR: Schools and districts started to see kindergarten as a way to jumpstart learning and these foundational skills

AWA: Over the back half of the 20th century, reading instruction became a bigger and bigger part of kindergarten. There were academic standards to meet. Expectations.

JLR: It’s been a full cognitive shift in how we think about what kindergarten is.

[BACKGROUND AUDIO]

AWA: This school-like version of kindergarten – and being in the same building as other kids – doesn’t go well for everyone. Take Phil Reilly from Philadelphia — who started kindergarten in 1981.

PHIL REILLY: So I remember my first day. The big kids making us stand up against the wall and trying to get us to curse. And I had never cursed. I was tiny. I had just turned five. I was probably one of the youngest in the class. I was like this is terrible. I was petrified.

AWA: And things got worse from there

PR: Memory number two: I get out of my seat to walk over to one of my friends and ask him if they wanted to come over to my house. And another kid hit me. So the other kid tells my teacher, so-and-so hit Phil. And she goes, ‘well, he shouldn’t have been out of his seat.’

AWA: So if you look at all of this through a cognitive, scientific lens, the question is does it make sense to put a little 5-year-old like Phil into a formal classroom? I posed that question to Melissa Libertus, a University of Pittsburgh professor who studies cognitive development.

MELISSA LIBERTUS: There’s nothing magic about the age of five or six that suddenly turns a switch in children’s brains, where all of a sudden it’s like, ‘oops, yes, now I’m ready for school.’

AWA: Melissa says babies start learning the building blocks of reading and math from almost the moment they enter the world. When scientists play a string of words for three-month old infants, they can see activity in the part of the brain that processes language.

ML: And when you play that same speech backward…

[BACKGROUND AUDIO]

ML: That part of the brain is no longer active.

AWA: So a little slug of an infant can distinguish human speech from other sounds. And the same goes for basic quantitative activities. The tiniest kids understand concepts of less and more.

ML: And they can tell the differences between what’s more and what’s less.

AWA: So we have these lingual and numeral instincts. They’re in us. What we call language or math are systems of symbols — or codes — that allow us to express these latent instincts.

ML: All that these numbers and symbols and math allow us to do is to be more precise in our calculations. To say, ‘Oh it’s exactly three! And it’s exactly 10!’

AWA: School, as we know it, is the place where we take these instincts and we learn how they match up with these human codes we’ve invented. And that leads us to the core question.

ML: When do you start introducing kids to these formal systems? And why?

AWA: That’s the hard part…

ML: So we’re entering a domain here that’s maybe a little bit more contentious.

AWA: Melissa says it’s different for every child. Some brains make these connections early. Some require more time and more specific kinds of training. Think about kids with dyslexia or its mathematical equivalent, dyscalculia.

Then there’s the social element.

When are kids ready to do what we now call kindergarten? When are they ready to sit at a desk for several hours a day? Or listen to a teacher? Or play nice with friends?

ML: What often happens is when kids are not ready for it, they often start having negative experiences in school And that just spirals out of control over time.

AWA: The reason kids tend to start kindergarten around the same age has nothing to do with science. It’s just unwieldy to run a system any other way. So it’s hard to know whether starting earlier or later is better for kids.

Stanford economist Thomas Dee and some colleagues tried to find out by using data from Denmark.

They looked at kids who started kindergarten really close to age five and those who started really close to age six.

On the whole, they found that the late starters had some advantages.

THOMAS DEE: We saw uniquely large benefits in terms of reducing inattention and hyperactivity.

AWA: But Thomas says the results should be interpreted with caution.

TD: The benefits are much more targeted. So when people sort of ask me, ‘how should we make decisions around whether a given child should delay or not?’ I will talk to them about this — this seems to be the particular benefit.

AWA: Should a kid delay kindergarten? Or maybe even consider skipping it?

Depends on whether they’re struggling to self-regulate. It depends on how regimented their kindergarten is.

If record numbers of kids are delaying their entry into formal school right now, the best we can say is this: It’ll be good for some. Not so good for others.

PR: There’s a little easel we have going on here, blackboard side, whiteboard side. Pull out some paper.

AWA: And that brings us back to Phil — Phil Reilly from Northwest Philadelphia.

Last fall, Phil had to decide whether to send his five-year-old daughter, Winnie, to kindergarten.

PR: We could have enrolled her in Philadelphia public school, and done the virtual school that way, which was an option.

AWA: But online school for little kids didn’t appeal.

PR: And I was like, well, I can teach them. Rather than having them sit in front of a computer.

AWA: Phil’s a former elementary school teacher and has a flexible schedule because he coaches cross country. And so on a typical day this school year he’s able to wake up, read the paper, do a couple hours of work with Winnie and her brother, Kaden.

PR: We can really knock out school in, to be honest, two hours, which gives a lot of time for going out for a hike in the park. You know, having fun and learning that way.

AWA: Phil says it seems to be going well. Winnie’s reading more. She can count to 100.

PR: Every now and then I’ll be like, ‘What if they go back to the school and I messed up and they’re not ready?’ And then I usually get over that. They will be ready because I know that they are learning and they are doing work.

AWA: When Winnie goes to first-grade next year she’ll have officially “skipped” kindergarten.

But her experience sounds more like what kindergarten used to be.

For The Pulse, I’m Avi Wolfman Arent.

MS: We’re talking about the role of research in education today.

There is a relatively new field called educational neuroscience that applies the lens of understanding the brain and nervous system to learning.

MS: How do you study these things? Do you put people in brain scanners and give them tasks, or how do you do this work?

FIRAT SOYLU: Sure, exactly. So we use different neuroimaging methods — the one where you put electrodes on the scalp and then look at the electrical changes on the scalp, which tells you something about the type of processing taking place in the brain.

MS: That’s Firat Soylu. He’s a professor of educational psychology and neuroscience at the University of Alabama.

MS: On the very most basic level, what do we know about neuroscience and learning? What, what happens in the brain as we learn? What has to be in place for us to be able to learn?

FS: What happens in the brain when we learn is there is change in the brain in principle, your brain creates new connections among the neurons. There are many billions of neurons in the brain, and then you establish new connections. And depending on the type of learning taking place, it might be more permanent and maybe not, right? So if I tell you my phone number, now you will remember it for a while, but you’ll probably forget it tomorrow. So for learning to be stable, one thing that we now know is that the affective components should be there too. That first, you need to care about what you’re learning, which we call motivation.

MS: Your emotional state plays a big role in learning. Are you anxious? Bored? Excited to learn? All of that matters. So, it goes way beyond understanding where the brain lights up, so to speak, when we do a specific task.

FS: The brain is in a body, the body is in an environment. It’s just this very complex system. It’s not a computer where you can actually store information, and it works very differently. There is a strong relation between the body and cognitive processing, including learning. Research in the last 20, 30 years, has shown us that there’s a strong relation between how we move our body, how we do bodily tasks, and how we learn and how we process information.

MS: How so, what kind of — what kind of bodily movements are you talking about?

FS: So just as a quick example, when you are learning mathematics early on, children use their fingers. They learn how to count, how to do arithmetic. Nut later on as adults, we still use some of the systems that we use for moving our fingers when we do mathematics. That connection is still there, but you don’t have observable behaviors, bodily behaviors.

MS: Oh, so I’m not going like ‘one, two,’ — I’m not like pointing my fingers as I do the math, but there’s still some kind of like nerve connection there?

FS: That’s right. You can think of it as an internal stimulation and this applies to many different cognitive processing. So, when you are processing language, for example, you still have these internal simulational sensory motor states. I mean, sensory motor meaning bodily systems. So it’s almost like, to make sense of what you are hearing, or to make sense of the type of mathematics that you are doing, you need to activate an internal experience in a sense. It’s a sensory motor simulation. And in neuroscience research, the way this is expressed is that you see the sensory motor areas being activated when you do cognitive tasks.

MS: So learning is not confined to the brain alone.

FS: I mean, we have to probably think about the entire body as the cognitive system. And according to some approaches, we also need to include the environment, like thinking about the entire mind, brain, you know, brain, body, and environment as part of the same cognitive system. Because now we externalize also our cognition. When we use tools, when you use a piece of paper and pen, or an iPad or a computer, you actually kind of distribute your cognition to the context. So this part of your current system now.

MS: Yeah. That’s, that’s a good point. I was just thinking about how I still very much learn by writing things down, like physically writing them down because that’s how I had to learn in school. And I think I made a lot of connections in just writing notes or in physically writing things down. But now of course, kids do that differently, so they probably learn differently, but it’s just interesting to think about how it all comes together.

FS: Yeah. I agree with you. We forgot how to write now, because we have things like writing always on the computers.

[LAUGHTER]

FS: I recently got a writing pad, like so that you can write on the computer and it was so good. I missed it so much. Like when I’m teaching courses and stuff, it’s like writing on the whiteboard. But I mean, you create a feedback loop when you do that, right. You know, you write, you put something out, it’s an external representation. And then you feed it back. So you create a feedback loop, uh, with the environment. You know, now that piece of paper is probably part of your thinking. I mean, you can think of it as part of the cognitive system now.

MS: Firat also talked to me about some general myths that a lot of people have bought into in terms of learning and education, including one that seems to be pretty popular.

FS: So learning styles is one of the main neuro myths. I mean, neuro myths are misleading notions about the brain and cognition. I think learning styles is one of them. There’s not any serious evidence for learning styles — that you have one mode of learning that’s like stable, and that you should just stick to it and learn through it. In fact, what we know about the brain and cognition is that it’s actually the opposite. That learning is multimodal. So when I say modal, I’m talking about different sensory and motor modalities that are involved. And it’s better when it’s multimodal. And also your preferred mode, if there is one, is likely to change. And it’s also likely to be determined by the environment.

MS: So if, if somebody says to you, ‘Oh no, I’m an auditory learner, or I’m a visual learner, or I’m that kind of learner,’ in your head, you’re thinking, no?

FS: I say no, because you know, when you get auditory information, that also triggers visual representations in your brain. Or when you see something that can trigger auditory experiences. Being exposed to stimulus in one modality triggers representations in other modalities.

MS: Are we at a point where this kind of science is informing education, or are we more using it to study existing approaches? Like is anything that neuroscientists are learning making its way back into the classroom?

FS: I think it has already happened to some extent, and it’s likely to happen more. So one example is for example, dyslexia. Experimental studies on dyslexia told us about mechanisms of dyslexia in the brain. Once you know that there might be something that’s not quite working well with the phonological system — because that’s what the experimental studies show — then you can start thinking about developing interventions, and that happens with dyslexia.

MS: Firat Soylu is an associate professor of educational psychology and neuroscience at the University of Alabama.

We’re talking about the role of research in education. Coming up…

PROMO: Homework was a given, no one questioned it. Homework is just something that you did.

MS: Should teachers stop with the homework already?

That’s still to come, on The Pulse.

SEGMENT 2:

MS: This is The Pulse – I’m Maiken Scott.

We’re talking about education, and how much research informs what kids do and learn in school. Could science lead to better approaches?

[BACKGROUND AUDIO]

MS: Homework is a lightning rod in many families. It ruins evenings and weekends, it piles up. It can make life miserable.

And there’s often that nagging question — is this really useful? It’s not just kids and parents wondering. Educators have questioned the value of homework, too. During the pandemic, this issue has gotten renewed attention.

Reporter Alan Yu has more:

ALAN YU: Dawn Siff is a mother of two in Queens. Her kids are five and ten.

And like many parents, she now has a lot to do at home.

DAWN SIFF: Just keeping up with my own business, and my own responsibilities, and then the fact that everybody’s home and I have to keep my children, like, on their Zooms…

[BACKGROUND AUDIO]

My fifth grader doing his homework. And also everyone is hungry all the time and also the house is dirty all the time.

AY: And so she was a little taken aback when her 5-year-old daughter’s teacher messaged her about homework.

DS: Your daughter isn’t doing any of her homework, and I just thought ‘Oh my god, homework for a kindergartener in the middle of the pandemic,’ like can’t we all just show each other a little bit of grace? Like surely this is not necessary right now.

AY: Dawn is in a group chat with friends who are also mothers — who were just as frustrated.

DS: And we will all just talk about how this is just too much right now. And that if your kid cannot like do their own homework themselves and take a picture of it and upload it, that we just don’t have the bandwidth to do that right now.

AY: And students are feeling the pressure, too.

Shakeda Gaines is the president of the Philadelphia home and school council, and talks to a lot of parents and students.

SHAKEDA GAINES: Children are crying. I literally sat there for about an hour and a half and they were every bit from 14 to 18 year olds, crying.

AY: Many teachers want to ease the tears and stress for students and families.

Several teachers told the Pulse they cut back on homework during this time. Some parents also report this happening. And the pandemic could bring people to rethink the value of homework.

People’s lives have changed a lot, and that could lead to a process that sociologists call “making the familiar strange.” You ask questions about practices you’ve just assumed should happen.

MARIAN DINGLE: When I began teaching, homework was a given. No one questioned it.

AY: Marian Dingle is an elementary educator in Georgia, and she has been teaching for over 20 years.

MD: It was something that you did as a child yourself, so no one really questioned whether or not homework was a good thing or a bad thing.

AY: Homework can achieve different goals depending on what it is. Students can apply what they learned in class to real world situations. Or they can practice or review what they learned in class. Or they can prepare for class the next day.

Marian started to question whether homework really accomplished those things when she had kids herself.

MD: Trying to grade all this homework, and prepare for the next day, and take this one to dance class, and this one to soccer, and that really started getting me to thinking about, what is this notion of homework that we have? Why is it that we believe that children don’t learn on their own without being assigned a certain particular thing that they have to do that they may or may not be interested in?

AY: If a student has to do homework that they consider to be dull busywork, it is not very effective. As an example, Marian points to a reading log. A student has to read a certain amount outside of school, write this down in a log, and get a parent to sign it.

And this reminded her of her own piano lessons as a child. She also had to log how much she practiced, and get her mother to sign it.

MD: During those times where I was doing a piece that I hated, it was like pulling teeth. And my mother would just get sick of me begging her to sign it, and she would just sign it, and of course it was meaningless.

AY: That made Marian think. Teachers can assign homework, and figure out if a student did a specific task. But it doesn’t really show that their students have learned anything. And so:

MD: I haven’t assigned homework in probably over a decade.

[MUSIC]

AY: Beyond questioning the value of homework as a learning tool, some teachers worry it could cause students to disengage.

Jenna Laib is an elementary school math teacher in the Boston area. She can still remember this one student from her very first year as a teacher. This student would not do his homework.

JENNA LAIB: And I had started with the same policy that all of the teachers on my grade level had which was if you don’t do the homework, you have to do it during recess. And I thought for some reason that that would be motivating to him, that he would want to do it. But it didn’t make any sort of change with him. And it was just heartbreaking to kind of watch him slowly go through it every day at recess and see him more and more disengaged. It felt like a power struggle that I didn’t want it to be.

AY: Some researchers argue that homework could have a negative impact on entire groups of students. From 2008 to 2012, Indiana University sociologist Jessica Calarco studied a school district. She observed what happened in classrooms — talked to teachers, students, and parents.

She recently published findings that focus specifically on elementary and middle school math homework. The research pointed to another issue with homework – it reinforced existing inequality.

For example, she remembers a mother who passed GED level math, and tried to help her son, whom Jessica calls Jesse, with his math homework. This is what Jesse’s mother told her

JESSICA CALARCO: She was on the verge of tears talking to me about how difficult helping her son with math homework was for her. She’s someone who the education system repeatedly failed. To then have to be expected to provide support for her son with math, and to feel just completely debilitated in that process, to feel like she was powerless to provide her son with the help that he needed to be able to be successful himself.

AY: And the teachers started to treat this student differently.

JC: He was not getting a lot of support at home because his mom couldn’t provide him with support at home. And the teachers, especially by middle school, really just wrote him off. And said like ‘this kid, we’re just not going to help him, because he’s not putting in the effort to do it,’ and just ignoring the challenges he had faced at a very early age in getting the support that he needed to be successful in school.

AY: Her team found that homework, especially in early grades, had as much to do with the resources and time that a student’s family has to support them, as it does with the student’s actual ability.

And if a student does not do their homework on time, teachers think this means they are not hard-working, or not smart. So the research concludes that homework can reinforce existing inequality and class differences.

We can see that homework can do some real harm, but it also has benefits if used appropriately. So how much homework should there be?

There actually is research that answers this question. The person that almost everyone cites is Harris Cooper, emeritus professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Way back in the 1980s, he went through every single academic study about homework to see if they led to any kind of consensus. He has updated this analysis, most recently in 2012.

And this is what he came up with:

HARRIS COOPER: The 10 minute rule. What that means is you take a student’s grade and you multiply it by 10, and that’s the number of minutes each night the student should be doing. So a second grader’s typical assignment should be about 20 minutes, a 4th grader 40 minutes, a 9th grader might be an hour and a half.

AY: He says that 10 minute anchor is based on research but it is not magic. Teachers should be able to move that up and down depending on the student. The basic idea is older kids can benefit from more homework, but it should never be excessive.

HC: The relationship between homework done and achievement, increases up until just about we get to the 10 minute rule, and then it levels off. Adding more homework after the 10 minutes doesn’t improve achievement.

AY: He says it also matters what the homework is. The best homework is something that includes what kids already like to do. It can be reading comics, it can be a little league player calculating and keeping track of their batting average.

HC: Homework assignments that helps kids realize the things that they are learning in school have applications to things that they enjoy doing at home is a good homework assignment

AY: But, you can’t fix the larger issues around homework just by having every teacher in the US reduce the workload, or change their assignments.

GRACE CHEN: It’s really tempting to think if we can just find the answers to what makes a good teacher, and we can just get all the teachers to do it, then all our problems will be solved.

AY: Grace Chen is a graduate student of education at Vanderbilt University. She studies math teachers and she used to to be one herself. She worked with Jessica Colarco on the study about homework.

GC: I think many teachers are aware that homework is not as fair as it seems like it could be. There are certainly many teachers who have thought about that, and decided to stop giving homework or to change their homework policies accordingly. But I also know teachers who feel sort of trapped and don’t really know what to do because for so long, the idea of school in this country is associated with doing homework.

MS: That story was reported by Alan Yu.

We’re talking about the role of science and research in education.

[BACKGROUND AUDIO]

Reading is one of the fundamental skills you are supposed to learn in school — and yet a huge number of kids don’t read well. In 2015, only 37% of 12th grade students were proficient or advanced in reading in a national assessment. Not even half!

SOYNA THOMAS: My journey has been painful and it’s still painful.

MS: Sonya Thomas is a mother of four in Nashville. She recently found out that her youngest child, CJ, has been struggling to read.

ST: Because remember that my son is still in school, and remember I’m still 45 years old and I’m a struggling reader. So the impact that this has had on me as a person, and as a mother, has been traumatic and devastating. But I’ll be okay and CJ, he’ll be okay. But what about the other parents that didn’t know or who still don’t know, like I know?

[MUSIC]

ST: I learned that he attended, ya know, most of the lowest performing schools in the school district, so I felt betrayed when I found out that he was in the 7th grade reading on a second grade reading level. It made me feel angry and hopeless. But it also made me want to fight for other children.

MS: Sonya is executive director of Nashville Propel, a parent-led organization that advocates for quality education and equity in public schools.

ST: And to me it’s criminal to send children through school and not give them adequate instruction and preparation. If we don’t do anything else in school, teach children how to read.

MS: But how you teach children to read – what approach is best – is at the center of a big debate. Sonya favors an approach called “the science of reading” – that emphasizes phonics.

LOUISA MOATS: Let’s take the word bread. [Sounds out “bread”]

MS: That’s Louisa Moats. She’s a leading researcher in literacy and champions this approach.

LM: The printed word bread has five letters in it. But the student has to first think or be able to think that bread is made up of B-R-E-D, four speech sounds. And that’s a prerequisite for understanding what those letters are doing.

MS: Louisa argues that teaching phonics is giving kids the ‘code”’ to break down words to their essential parts sound by sound, symbol by symbol.

And that kids have to master these basics before they move on to more advanced reading …

[MUSIC]

LUCY CALKINS: Reading is complicated and there are a bunch of different things that kids need to learn.

MS: That’s Lucy Calkins, also a literacy expert, and the director of the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project at Columbia University. Her program is basically on the other side of this debate over how to teach reading. Lucy says teaching phonics is important, but kids need more than that.

LC: They need to learn comprehension. They need to learn vocabulary to discuss text and to think about text. So teaching reading is broad and it involves a number of different strands.

MS: Lucy is in the camp that people often refer to as balanced literacy.

LC: And balanced literacy means that really we are trying to give kids a comprehensive education that includes phonics and includes a big emphasis on comprehension strategy instruction and on knowledge development.

MS: Kids get to reading actual stories quickly, there’s an emphasis on the joy of reading and engaging students with books.

LC: Part of it will be having teachers read aloud to them and open up the world, help them to learn about all that the world contains, engaging them in conversations about books.

MS: But Louisa and others argue that this approach — which is used in many schools across the country — doesn’t work for a lot of kids. And the stakes are just too high:

LM: Well, it is so well documented that if you are not a proficient reader by 2nd or 3rd grade and you haven’t achieved this ability to look at a new word and decode it and store it in your memory — basically that’s the mechanism — or you don’t know what these words mean, that everything else about your academic career is in jeopardy.

MS: Louisa says her phonics-heavy method leads to better results, and research backs that up.

LM: One of the most well-established scientific findings is that if kids don’t learn phonics, they are destined to be poor readers. They are destined to be very limited in their reading.

MS: Louisa says when the state of Mississippi adopted this approach, kids scored better in national achievement tests. So I asked her — why haven’t more schools across the country implemented this method in the classroom?

LM: There are a lot of culprits, and to teach phonics you have to know how our written language works and it’s more complex. So in order to learn how to do this well, you have to have been educated as a professional about how our language works. So my kindest response to why teachers don’t practice what we know from science is that they’ve been isolated from and insulated from the scientific base concepts that should drive reading instruction and they simply don’t know the content.

MS: For Lucy Calkins the argument is not about phonics yes or no — it’s more about how much phonics is beneficial — and what you might lose when you focus so much on the basic components and not the text itself.

LC: it’s really about the balance, it’s nuanced differences between these because there is tremendous agreement. One of the differences is how much time is given to actual reading, to continuous reading of texts. And in balanced literacy that’s a priority. And so kids will be reading for longer in balanced literacy classrooms, and in some other classrooms they’re spending more time on discrete ditto sheets and drills to sort of make sure that they are mastering the smaller pieces of reading.

MS: We always want science to tell us what to do and how we can quantify this and that but there is so much about education that strikes me more of an art. It’s about the teacher, and the passion of the teacher, and how the child feels in the classroom, and how the child’s curiosity is inspired. So there is a lot in education that we cannot quantify.

LC: It’s absolutely the case that the art of teaching is critical, and that relationships are everything. But also I think that we need to remember that the science of reading needs to take into account the whole day. So you can do a study that shows that if you spend an hour a day teaching vocabulary, the kids’ vocabulary will get better. But that study does not tell you, how do you spend your whole day? What are you not doing during that hour? Perhaps that hour took up recess or playtime or time to read aloud and to talk about books.

MS: That’s literacy expert Lucy Caulkins. We also heard from Louisa Moats.

[BACKGROUND AUDIO]

SEGMENT 3:

MS: This is The Pulse, I’m Maiken Scott. We’re talking about the role of research in education. Teachers in US public schools are overwhelmingly white -—while their schools often serve a very diverse student population. Many experts say this imbalance is having an impact on students’ learning.

Sojourner Ahebee reports:

SOJOURNER AHEBEE: In second grade, Noah Reilly was assigned to do an immigration project.

He and his classmates had to write a short paper about their ancestors’ journey to the United States and make a doll that represented their family’s story. But Noah had a feeling his doll would look different.

NOAH REILLY: My mom said that I would probably be the only one with this one, and I was the only one.

SA: For his project, Noah wanted to tell the story of his mother’s family, who’s Black.

Noah is a mixed-race child who attends a school in the suburbs of Philadelphia where Black children make up only 5 percent of the student population.

Noah’s teacher was white.

MONET REILLY: I think it was hard for the teacher to understand why the project was an issue, that not everyone has an immigration story.

SA: This is Noah’s mother, Monet Reilly

MR: There were obviously a large group of people who came here as slaves, and not as willing immigrants.

SA: The project forced Monet to discuss slavery with Noah, something she wasn’t ready to do.

At the time, Black teachers made up only one percent of Noah’s school district.

MR: And I think if there were more teachers of color in their school, someone could have looked at the project on the team and been able to point out the many points of inappropriateness.

SA: Noah is in fourth grade now, and he has never had a Black teacher until this year.

This absence of Black teachers is a reality for many Black students all over the country — and it’s impacting their educational outcomes.

Cassandra Hart, an associate professor of education policy at UC Davis has researched this:

CASSANDRA HART: and what we wanted to look at is whether there were longer term outcomes.

SA: Cassandra Hart, an associate professor of education policy at UC Davis has researched this.

CH: So If you’re matched to a Black teacher in your elementary school years does that still matter down the line for things like your high school graduation, and ultimately your college enrollment outcomes.

SA: Cassandra and her team found that Black students who were exposed to Black teachers by third grade were 13 percent more likely to enroll in college.

Cassandra says if kids had two Black teachers by third grade, the likelihood of college enrollment jumps to 32 percent.

CH: One possibility is that there may be role model benefits. So having a Black teacher in front of the class, being a subject matter expert, might act as a role model and increase children’s long term aspirations for themselves.

SA: She says there’s also good evidence that students are responsive to the expectations that we hold for them.

Research shows that Black teachers tend to hold slightly higher expectations for their Black students. And Black educators are more likely to use references or examples that tap into the lived experience of their Black students.

CH: And again that might end up producing better immediate outcomes for them potentially, longer outcomes for them as well as they kind of make or create visions of themselves as students.

[MUSIC]

SA: The piece you’re hearing is performed by Aaron Taylor. He’s a Black music teacher at a middle school in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Neither of his parents graduated from college, and he didn’t always think that college was an option for him. But growing up, music was his source of solace.

AARON TAYLOR: I’ve always had a lot of energy and music was a way not only to calm the energy I had but to put it somewhere.

SA: Starting in 5th grade, Aaron attended performing arts schools in Pittsburgh.

And during those years, he developed a close relationship with his African American trombone instructor who gave him a key piece of career advice.

AT: But it wasn’t until my 11th grade year where I sat down and I talked to Mr. Jackson and I told him I want to go to school to be a music performer. And he recommended, he was like have you ever thought about being a teacher?

SA: Inspired by Mr. Jackson, Aaron went to college to become a music teacher.

At the middle school where he teaches, only 11 percent of the teachers are Black, though almost half of the student population is.

AT: I think my students of color definitely depend on me in a different way. They see me as a role model, they see me as an advocate for them to succeed. They see me as someone who’s made a way when there wasn’t a way.

SA: Aaron makes sure his curriculum is reflective of the student population — over 25 different countries are represented and 17 different languages.

AT: I do have units where I talk about music from different parts of the world so for the students who are coming from these parts of the world, they can also provide a bit of their own authentic experience.

SA: Aaron likes to create a sense of community in his classroom, where all cultural perspectives are celebrated. The experiences of his students become a tool for teaching and learning — and research finds that’s effective.

Constance Lindsay is an assistant professor in educational leadership at UNC Chapel Hill.

CONSTANCE LINDSAY: Instead of viewing what students bring to school from a deficit orientation, you’re really viewing it from an asset-based orientation.

SA: For Aaron, every opportunity he gets to stand in front of his students and teach is one more chance they get to see what’s possible for themselves.

AT: When you go to a classroom where you feel you are wanted, desired, and respected, you feel a part of it.

[OUTRO]

MS: That story was reported by Sojourner Ahebee, our health equity fellow.

That’s our show for this week — The Pulse is a production of WHYY in Philadelphia.

Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Our health and science reporters are Alan Yu, Liz Tung, and Jad Sleiman. Charlie Kaier is our engineer. Xavier Lopez is our associate producer. Lindsay Lazarski is our producer.

I’m Maiken Scott, thank you for listening!

Subscribe to The Pulse