Your baby’s brain: If you want to build a better mind, tell stories

Reading, even talking, to a little one furiously directs neuron fibers to places in the brain where the magic of language, memory and attention develop.

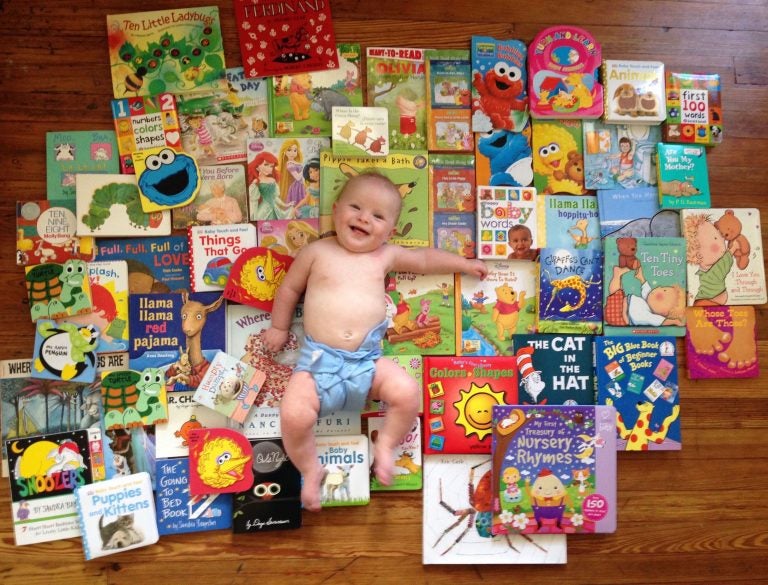

Josie Shipley received many books for her 6-month birthday. Her mother, Nicole Chaney, requested extras to donate — 60 in all — to new mothers in 2015 at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, where she worked. (Courtesy of Nicole Chaney)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

Maybe your toddler knows something you don’t know. Every night, she insists she isn’t sleepy, and she wants you to read one more book …

New research using functional MRI shows your little one is right. Reading, storytelling, looking at pictures, counting the bears, showing Mommy what the caterpillar ate or telling Daddy what color Pete the Cat’s shoes are — the more of it, the better, neurologists are finding. These activities furiously direct white matter, the neuron fibers to those places in her brain where the magic of language develops.

The interaction between you is helping to establish her vital, lifelong neural groundwork — things like memory development, attention, information processing, decision making, and more. It’s setting one of the habits that might help establish how healthy your child becomes as an adult, too.

And the earlier you interact, the better, the research shows. Much of the evidence is not just with toddlers, but also with infants whose umbilical stumps are still attached.

The critical bond that forms can’t be overemphasized or overestimated, research shows. In two papers in 2018, researchers at MIT using neuroimaging techniques reported, in essence, that building the fibers that eventually connect to establish this cognitive function is enormously affected by a child’s early, consistent exposure to a “conversational experience.”

Socioeconomic status doesn’t matter, the researchers wrote: What matters is the back and forth between child and adult, and the constancy of it. Reading aloud to a child, for instance.

If Mom or Dad can’t read, just telling stories works, too.

Rachel Romeo, a postdoctoral fellow in translational neurodevelopment who was among the papers’ authors, said the preliminary findings show that the more interaction there is, the thicker and larger the frontal parts of the brain involved in language and cognition become.

“There’s a pretty linear relationship between the amount of conversational interaction children experience and their cognitive and neural development,” Romeo said in an email interview.

How much conversational interaction?

“We haven’t found any evidence of a ‘quota,’ so to speak, though we are actively investigating this amongst many more families with a wide variation in their communication practices, and in children of different ages and abilities,” Romeo said.

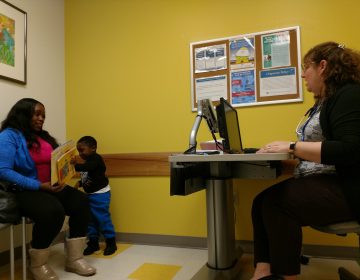

Conversational interaction between parent and child can take non-spoken forms, for instance. James Guevara, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and professor of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, said his patients have included deaf children who learned sign language by the time they were 2 years old. Studies are also beginning to look at how the conversation takes place when a parent has sensory issues.

When there is no back-and-forth communication, no reading, no intimate time, this is what happens, child experts say:

- Traumatic experiences are more difficult to absorb, and the normal stresses of life aren’t not coped with well.

- Vocabulary can be significantly stunted.

- Behavior problems are more likely to develop.

Children who fall into this category are generally not ready to perform kindergarten tasks, researchers say: The odds of their reading at a third-grade level, the benchmark year, are not good.

Parents can buffer the effects of life’s ugliness for their children by creating a strong bond through interaction, said Nikki Shearman, a biochemist turned reading interventionist.

“To be successful,” Shearman said, “you have to high-quality executive function. You need language and literacy and resiliency” to counter adverse childhood experiences.

A 2016 neuroimaging study showed that babies arrive wired for sound: On hearing their mothers’ voices, the left sides of their brains lit up like lightning, via functional magnetic resonance imaging and near-infrared spectroscopy.

Cognitive development “is largely a matter of neural enrichment,” Usha Goswami, director of the Centre for Neuroscience in Education at the University of Cambridge in Britain, wrote in 2015.

Children will learn to gain control over how they think, “inhibit problematic actions, and develop conscious control over … thoughts, feelings and behaviour,” Goswami wrote.

But it doesn’t all happen at once.

“Attention, memory, the ability to monitor errors, and to process information that flies into the brain, these executive functions are developed early in life; not all together, but piece by piece … even in the first few months after the baby is born,” said Tzipi Horowitz-Kraus, scientific director at the Reading and Literacy Discovery Center of Cincinnati’s Children Hospital Medical Center and director of the Educational Neuroimaging Center in Technion, Israel.

“When the child begins to read,” she continued, these pieces come together, “like an orchestra.”

Horowitz-Kraus and her colleagues have been using functional MRI to look at babies’ and toddlers’ brains for some time.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging, which emits a radio frequency picked up by the magnetic field found in the brain’s hydrogen atoms, follows blood flow. Any blood-flow increase delineates the part of the brain that is getting more energy because it is more active.

Unpublished data (recently accepted for publication, Horowitz-Kraus said) shows neural network involvement in 75 infants, just weeks old, in areas of their brains involving attention and processing as they are being read stories.

“We see cognitive control networks kick in, they are part of the process. You would think it’s just intuitive ability to listen to a story,” said Horowitz-Kraus, who started researching executive function and its connection to literacy because both her brothers are dyslexic.

She also wanted to see how early in life a child had to nurture those abilities to be successful at reading, and what could harm those abilities. Her team’s work, again using fMRI, has found that children with various diagnoses — dyslexia, mood disorders, behavioral disorders — all have reading problems involving different cognitive areas.

“We found many connections to executive functions,” Horowitz-Kraus said. “It is much more basic.”

As basic, and fundamental, as “The Cat in the Hat” and “Go, Dog. Go!”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.