Work of Barnes friend, artistic guide William Glackens featured at foundation

ListenThe Barnes Foundation, on the Parkway in Philadelphia, is exhibiting the work of an artist who played a critical role in the creation of the famous Barnes Collection.

William Glackens, a boyhood friend of Albert Barnes, is the subject of traveling exhibition, the first museum retrospective of his work in 50 years. Beside his importance as an American modernist, he was a seminal influence on Albert Barnes as the latter began assembling one of the finest art collections in the world.

The two met as 13-year-olds in Philadelphia’s Central High School in 1885, playing baseball together and taking drawing classes. Upon graduation, Glackens went directly into the newspaper business as an illustrator (always keeping up his studio practice), while Barnes went to the University of Pennsylvania to study medicine.

While Barnes became very wealthy developing pharmaceuticals, Glackens began a love affair with the city of Paris. He saw the artists there were onto something new and exciting: they seemed to be having fun.

“Artists were leaving the very dark, very reportorial narrative, the sort of thing [Glackens] had been doing, and moving toward more freedom, more anecdotal subjects, toward bold, saturated colors,” said independent curator Avis Berman. “France, as a way of life, influenced him. He only wanted to eat French and Italian food. He wanted garlic and wine. He liked the way Europeans lived.”

The first room of the Barnes Foundation’s temporary exhibition gallery has two early cityscapes by Glackens, richly painted with grays, browns and dark greens. The second room has his newspaper illustrations, including several done while embedded with troops during the Spanish American war, during which he was stricken with malaria.

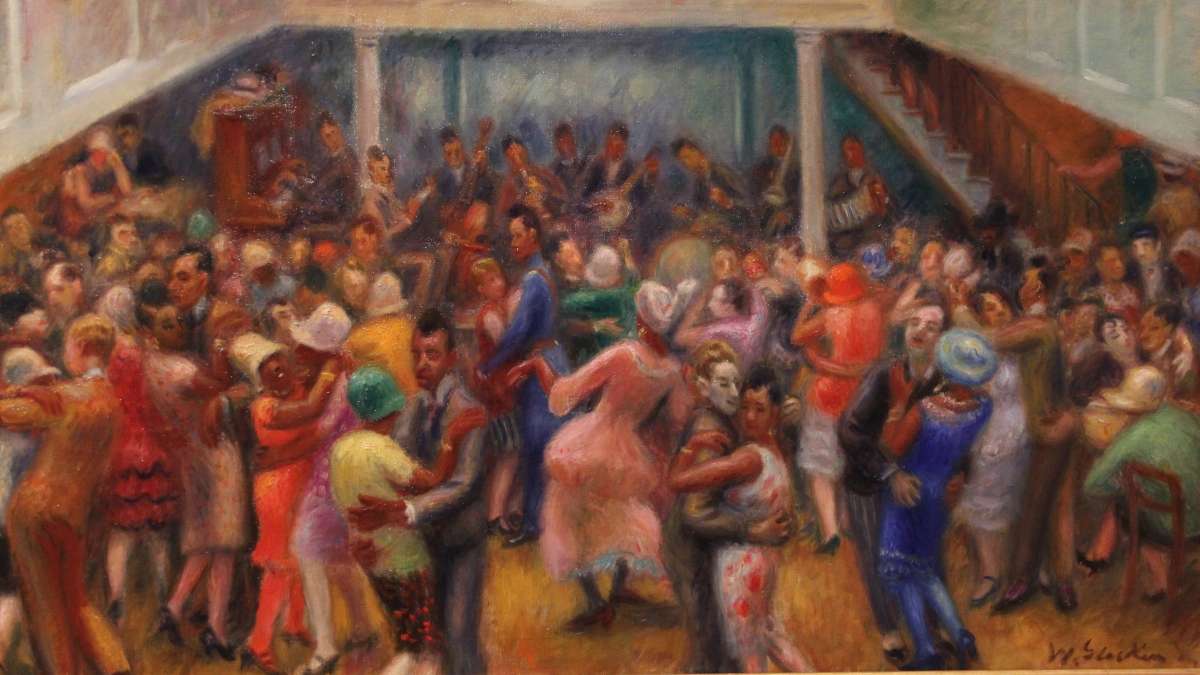

Color fills the third room — and the rest of Glackens’ career. Around 1905, his palette featured pink, lime green, and powder blue with which he richly rendered the folds of a silk gown in “At Mouquin’s.” He juxtaposed daubs of paint directly on the canvas, like the impressionists, to paint himself and his wife, Edith, as “Vaudeville Team,” a picture that has never been exhibited since Glackens painted it in 1909.

Return and reacquaintance

He returned from Paris to New York and joined The Eight, a group of subversive artists who later became the Ash Can movement. Their 1908 exhibition was a daring show of European-influenced modern art that shook up the New York establishment.

Shortly after, he heard from his old friend Albert Barnes.

“They had already established a wonderful relationship in their boyhood,” said Barbara Anne Beaucar, a Barnes Foundation archivist. “That playfulness, that love of fun, comes through as grown men ensconced in their careers.”

Beaucar has arranged a sidebar exhibition at the Barnes Foundation based on the letters between Glackens and Barnes, including a recipe for apple wine, which the two would subsequently make, and drink, together.

Barnes, busy running a pharmaceutical factory, was interested in maintaining an educated workforce. He had started collecting art and began to see it as an educational tool. He wanted people to appreciate art from the artists’ perspective, so he approached Glackens for help.

“Glackens felt Barnes had been collecting very safe paintings. I’m sure they were nice — Barnes had a good eye,” said Beaucar. “Meanwhile Glackens had been in Paris, and he knew something big was happening. He suggested to Barnes that he start collecting moderns.”

Treasure hunting in Paris

Smitten with the idea, Barnes handed $20,000 in cash to Glackens in 1912, then sent him to Paris to scoop up all the moderns he could. Barnes trusted his friend’s taste completely; he had no reservations or instructions on what he could buy.

Glackens returned with three paintings by Paul Cezanne, five by Auguste Renoir, Pablo Picasso’s “Young Woman Holding a Cigarette,” Vincent van Gogh’s iconic “The Postman,” a Camille Pissaro and several others.

The haul pushed Barnes into modern art.

Did Glackens shape the core values of the Barnes collection?

“A lot of people give him credit for that. Barnes does not,” said Beaucar. “Barnes wrote an article about the foundation in 1923 for The New Republic, and he did not give Glackens credit for helping him establish the collection.”

Barnes may have felt guilty about the omission. Beaucar has a long letter he wrote to Glackens’ wife, Edith, apologetic in tone but asserting that while his friend helped him greatly, the vision of collection was all Barnes.

“Because he knew him and trusted him, and their friendship was rekindled, he did not give Glackens instructions on what to buy,” said Berman. “When Glackens came back, Barnes took care not to have anyone advise him.”

Barnes, and beyond

The “William Glackens” exhibition stop at the Barnes (through Feb. 2) pays close attention to the relationship between Barnes and Glackens and the scouting trip to Paris in 1912.

This venue is the only one where visitors can see all seven Glackens paintings included in the 1908 exhibition of The Eight (the traveling show and the permanent gallery flesh out the entire series) and 48 other works by Glackens, which Barnes collected, on display in the permanent galleries.

The exhibition itself goes well beyond the relationship with Barnes. Immediately after the scouting trip to France, Glackens exhibited in the groundbreaking Armory Show in 1913, which firmly put modernism into the American scene. His style continued to evolve as he painted portraits, still-lifes, and crowded streets and bars.

The final painting in the show is “The Soda Fountain” (1935), borrowed from the nearby Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. It is a painting of its moment, two young women in contemporary dresses casually seated at an ice cream bar. It has the softness of an Edward Hopper, and the informal insouciance of a modern — the woman facing us is caught wiping her mouth.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.