With half of 2015’s murders unsolved, effect of Philly cash rewards is questioned

Listen

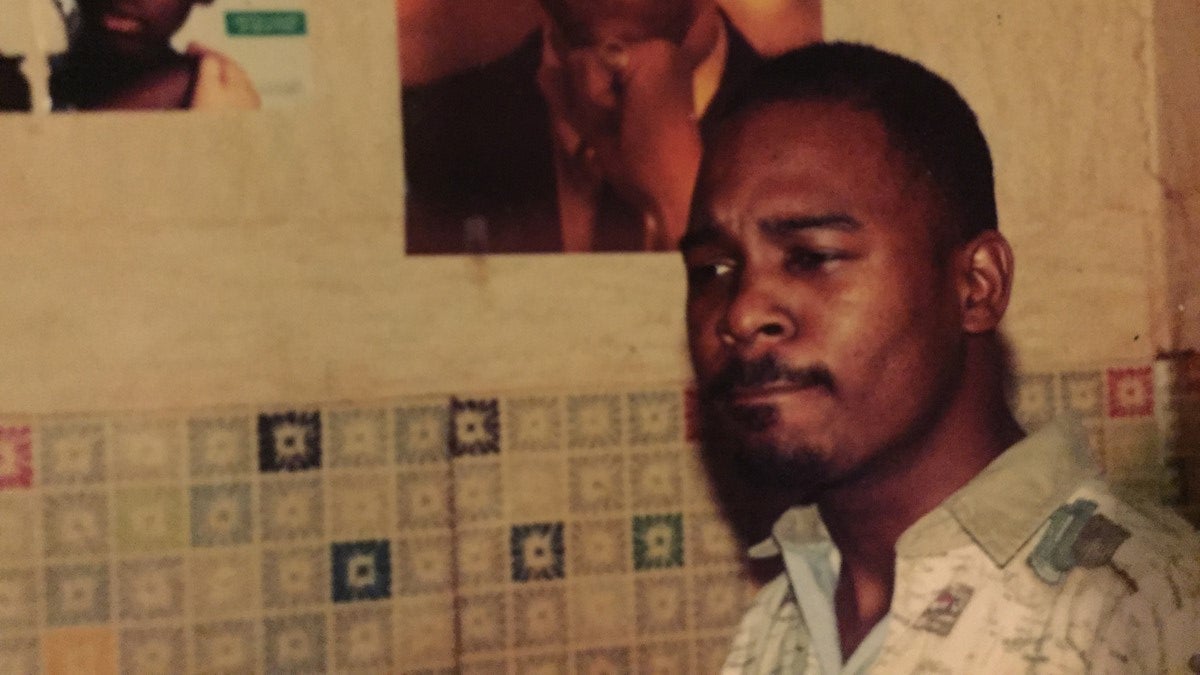

Tony Harris, 50, of Southwest Philadelphia, was murdered at his home in October. This case remains unsolved.(Photo provided by family)

On Oct. 12, three teenage boys with bandannas covering their faces broke into a home on Ruby Street in Southwest Philadelphia, hellbent on robbery. After a furious standoff, the boys shot and killed 50-year-old Tony Harris in front of his two youngest children.

Around 11:15 p.m., police arrived to the scene in a stretch of squat, two-story, vinyl-sided row homes in the city’s Kingsessing section. When they entered, they found Harris bloodied but still conscious and talking. He was rushed to Penn-Presbyterian Medical Center and pronounced dead hours later.

The middle child of five who dabbled in electronics from an early age, Harris was a computer repairman by trade but also a mentor to dozens of kids around his block. Now he’s among nearly half of the 280 city murder victims last year whose cases remain unsolved.

In the months since, Harris’ loved ones have felt staggered, trying to climb back through community support and the passage of time.

“He was my best friend,” said Harris’ brother-in-law Lloyd Williams, who now lives in the house in which Harris was killed. “Every day, every day. Every room in this house, I see Tony.”

Adding pain to the grief is how close it seems police are to homing in on the suspects.

“You know, the streets talk. We kind of have an idea of who the people are,” Williams said. “But it’s not enough evidence for the police to be able to make an arrest. Something to make it stick. It’s been really hard on us, just because we’re not getting any closure.”

That desperately-sought closure escapes many families across Philadelphia.

Police call the percentage of killers they arrest the “homicide clearance rate.” Last year’s 52 percent clearance rate was well below the national average of 64 percent; in 2013, Philadelphia topped that, at 71 percent. Officials don’t have a complete explanation of what is driving the number down, but many say the “stop snitching” culture persisting in many communities is an undeniable factor.

“It’s extremely frustrating,” said Jennifer Selber, the chief of the city’s homicide unit. “Especially because when we actually arrest people, our conviction rate is over 90 percent. So we’re incredibly successful in protecting people and keeping communities safer when we can actually make an arrest.”

T-shirts bearing the “stop snitching” slogan on bright red stop signs more than a decade ago first popularized the idea, then it gained further notoriety through DVDs circulated in Baltimore. In those videos young men dissed and threatened those who cooperated with the police. And now, though the credo is professed less as a fashion statement, it exists in more subtle ways, holding the kind of sway that investigators can’t muster the means to undo.

“People won’t even cooperate with the police any more because they’re in danger, they don’t trust them,” said West Virginia University sociologist Rachael Woldoff, who has studied the phenomenon. “They don’t see what the payoff is going to be. So what if someone goes to jail? How does that benefit them personally?”

Philadelphia officials have an answer to that question. In recent years, officials started offering $20,000 for anyone who can offer information that leads to the arrest and conviction of a killer. According to records obtained from the city, Philadelphia has paid $633,000 to people who’ve offered witness testimony, or other crucial information, since 2013. There is a $250,000 line item in the city budget for crime awards, and cash awards connected to closing homicide cases account for the largest share of them.

“Well, there’s some people that $20,000 is motivation to come forward and share information,” said District Attorney Seth Williams. “There’s some people that $20,000 is not enough. Because they’re so worried about retaliation, or being shot, murdered, having their car keyed.”

When asked if he supports the awards, Mayor Jim Kenney punted, saying he’ll leave that decision up to crime-fighters. But he did say that getting a little richer shouldn’t be the only reason someone speaks out.

“I think you should want to solve homicides, and crimes, based on being a good citizen,” Kenney said. “You should want to solve crime because it makes your community safer, not because someone’s giving you a check.”

Nationwide, the homicide clearance rate has been ticking down in recent decades. Possible theories include prosecutors wanting only open-and-shut cases leading to quick plea bargains; that police forces have shifted resources from solving crimes to preventing crimes; and that the public’s distrust of police has exacerbated lately.

And that spills right into the stop snitching debate.

Woldoff says it’s likely the main reason why Philadelphia’s cash awards have delivered mixed results. Perceptions, she says bluntly, are powerful.

“Twenty thousand dollars is that going to pay for the funeral expenses of your entire family, your kids, your nieces, your nephews, your mom? These are real concerns people have,” she said. “That if they’re seen as cooperating that $20,000 isn’t going to get them very far.”

It’s unfortunate, Selber says, because the Philadelphia police are almost always closed in on the suspect. Yet without enough evidence to arrest, they’re stuck.

“Because those very people are victimized by having those killers live in their neighborhood,” she said.

Thomas Hargrove runs the national Murder Accountability Project. He said cities with low rates of clearance always have higher rates of murder.

“That should hardly be surprising,” Hargrove said. “If you’re not catching your killers, that means you have killers walking the streets. What’s going to happen in that situation? Well, you’re going to have more violence than average. Clearing cases saves lives.”

He said clearing murders provides communities a sense that “this city isn’t going to hell.” He compared it to “broken windows” policing approach in that the more murders remain unsolved, the greater the community feels lawless and hopeless, perhaps emboldening even more offenders.

Financial perks for solving crimes, Hargrove notes, have been around for a while. What tends to work better, though, is engaging the community in other ways. Having neighbors knock on doors to put out feelers, relying on neighborhood associations.

“Usually that is through efforts that more involve smarter policing, and especially involve working to create an new atmosphere between the city and the people,” he said.

Selber at the DA’s Office says that this is already in motion. They partner with many community organizations to investigate murders and they relocate 60 to 80 witnesses and families a year who fear some kind of reprisal after cooperating with police. Financial assistance is provided in some cases, as well as assisting families or witnesses with a security detail.

Prosecutors have been increasingly taken other steps to reassure skittish informants. For example, some witnesses avoid public preliminary hearings and instead deliver sworn testimony to an indicting grand jury, keeping it secret until two months before a trial.

Selber said in the immediate aftermath of a murder, the case is “really hot” and fears are heightened at that stage.

“By the time the case goes to trial, it might be a year and a half later, and things have cooled down,” she said. “And it’s easier for witnesses to come forward.”

When plainclothes homicide detectives go to murder scenes, she says they will sometimes surreptitiously slip cards to people. Community residents might discreetly strike up conversations with them out of the side of their mouths. Nothing too conspicuous.

“They’ve even had people that want to look like they’re being arrested, so that they’re looking like they’re being taken down against their will and they’re not being cooperative,” she said.

Indeed, the DA’s Office is willing to stage an arrest if a witness requests it. Anything it takes, Selber says, to put a witness at ease.

Selber says sometimes witnesses have legitimate reasons to be worried over revenge-seekers. Although in the majority of cases, the angst is inflated.

“It’s a culture of fear, more than a reality, of witnesses actually being injured or killed,” Selber said. “That is such a small percentage. So what we’re combating is a pervasive fear.”

Evette Harris, the sister of Tony Harris, says the entire family is still moving through the motions of recovery. Hope, however, hasn’t wavered. Tony Harris’ widow, Amber Crane, is raising their children in a new house. She hasn’t returned to the Ruby Street home since the day her husband was murdered. Her spirit remains sapped by the life-changing night, but the whole family agrees: rounding up the shooters would accelerate the healing process.

The tenacious culture of not speaking up about a murder, Harris said, is misguided.

“It’s difficult. It’s frustrating,” Harris said. “But I do think they’re going to find these guys.”

“People really forget what the snitch is about,” she said. “Snitch is when you tell on each other. You’re not a snitch if you’re doing something to protect your family, your community, your friends.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.