Climate change may be the new threat to the Wissahickon Creek

It was “bad news-good news” for the crowd who packed the auditorium at Springside Chestnut Hill Academy School in Chestnut Hill on Thursday evening. They were there to hear the news about the state of Wissahickon Creek, the jewel in the crown of Northwest Philadelphia’s parklands.

The bad news was that the creek’s waters are in poor condition as rated by many measures of its ecological health. The good news was that it hasn’t gotten any worse in the last 15 years.

The occasion was “A Creek in Crisis? A Town Meeting on the Health of the Wissahickon Creek,” sponsored by the Wissahickon Valley Watershed Association (WVWA) and Springside Chestnut Hill Academy, with support from the Friends of the Wissahickon (FOW) and Chestnut Hill College.

Moderated by Patrick Starr, vice president of the Pennsylvania Environmental Council Southeast Regional Office, the event featured 15-minute PowerPoint presentations by a panel of environmental experts who examined numerous threats to the Wissahickon.

Starr called the creek “Iconic” because of its beauty, use as a recreation space, and a source of drinking water for Philadelphia. It was designated as a National Natural Landmark in 1964, one of first in nation, and has been intensively studied since 1967, with more data gathered on its watershed than any other in the area.

Climate change

Carol R. Collier, executive director of the Delaware River Basin Commission, told the audience that we’re seeing bigger storms hit the region and the stormwater runoff is polluting the waters.

Collier says the Wissahickon is a ‘small but significant part.” Water from the Wissahickon, for example, supplies about 10 percent of Philadelphia’s drinking water.

Over the 30 years or so from 1970 to 2000, she noted, “The creek pretty much behaved itself. Since then we’ve had some big storms with lots of flooding.”

Collier noted that formerly a major problem in the Wissahickon’s watershed had been lack of stream flow in its upper stretches because upstream municipalities were draining groundwater out of its basin by taking drinking water from deep wells. Those water authorities had decreased the amount of well water they used and the situation had stabilized.

Now the problem is the reverse: too much flow during peak storm events. But since 1999 a series of heavy storms including hurricanes and intense summer thunderstorms had caused severe flooding. Much of the reason for that, she said, was a long-term change in the climate.

The area used to receive an average of 45 inches of precipitation, she said, but “since 2000 it”s been 52 inches.” And the outlook, she indicated, was for more of the same: “a greater intensity of storms, more precipitation in the winter months, and warmer summers. We’ve been working at extremes, floods and droughts.”

Among her recommendations for action were retrofitting stormwater catchment basins to slow the rate of runoff and increasing vegetation cover. She says we have to improve ways to get water back into the ground, “We have to strategize now.”

We use less water

Chris Crockett of the PWD followed, first giving some basic facts about water usage in Philadelphia, and the history of water management efforts here.

“Basically, Broad Street is the dividing line,” he said. “East of Broad you get your water from the Delaware, west of Broad it’s from the Schuylkill,” including the Wissahickon.

He said there had been a decline in the past 15 years of so in the amount of water that the average household uses daily, from about 210 gallons to 150, largely due to the use of more efficient fixtures and the rising cost of heating water.

He noted that in the late 1800s the city had purchased the land along the Wissahickon in order to be able to close the mills that once lined its banks and were a major source of pollution to the drinking water taken from the Schuylkill River. And he showed a slide of a report on water quality issues that the PWD had commissioned in 1885.

“The issues weren’t that different: sewage, development, lack of management of resources,” he said. “If you read it you feel like you’re stepping back in time.”

For the PWD, he said, the result is “Every time we remove a natural resource that provides nature’s protection we have to engineer that protection … but we’re playing catch-up all the time. The lesson is that we can’t engineer our way out of everything.”

But, he added, “There is hope,” giving the example of the newly-created Saylor’s Grove wetland in the triangle contained between Lincoln Drive, Wissahickon Avenue and Rittenhouse Street. It slows run-off, helps get water back into the ground and provides habitat for wildlife, he said.

Bugs on the front lines

Dr. John K. Jackson, a biologist with the Stroud Water Research Center, began his presentation with a slide of fearsome-looking aquatic insects. A self-described “bug guy,” he said of the insects on the slide, “They’re ugly but pollution-sensitive species are our canaries in the mineshaft” – indicators of the health of the water they live in.”

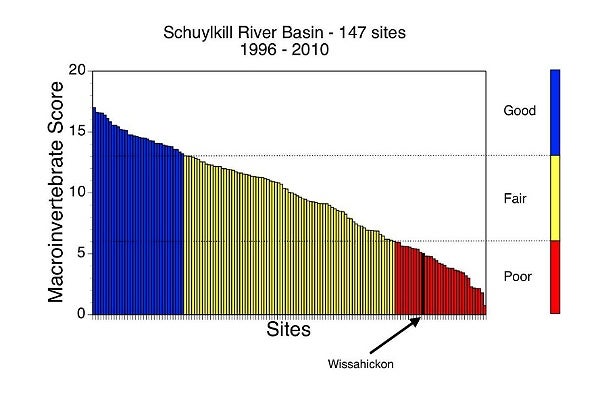

By that standard the Wissahickon is doing poorly, near the bottom of the 147 sites the Stroud Center monitors in the greater Schuylkill River watershed.

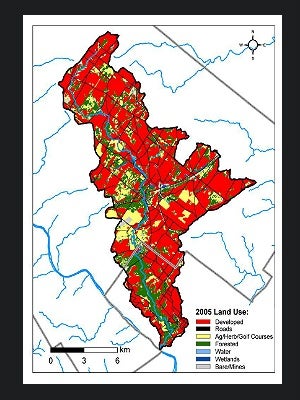

The cause is the large number of people – 900 per square mile – who inhabit the Wissahickon watershed. “The answer to the problem is to break the connection between the people and the water,” he said.

That would be easier said than done since, Jackson noted, the population of all the surrounding suburban counties had more than doubled since 1960. “It has taken 300 years of development to get to this point,” he said. “Turning it around will take a lot of time.”

At present, a staggering 95 percent of the water in the lower Wissahickon is treated waste water that has already been processed in upstream plants. “None of those treatment plants are doing anything wrong, they’re just overwhelming the ecology,” he said.

The good news was that despite population growth, the stream was probably in better shape than it was half a century ago and that water quality has not deteriorated – in the 15 years the Stroud Center had been monitoring it.

After a question and answer period, the panelists summed up their views of what needed to be done. All called for political involvement on the part of citizens who cared about water quality. Jackson said, “Be vigilant, it’s really important. Ask the tough questions: is this the best we can do, is this going to make the watershed better?’ And we also have to check up on how things are going, we have to ask for the evidence. It’s time for you to ask.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.