Will robots take your jobs? Why this is such a hard question to answer

A new report says Philadelphia will do quite well compared to other places in the U.S. as more work gets automated.

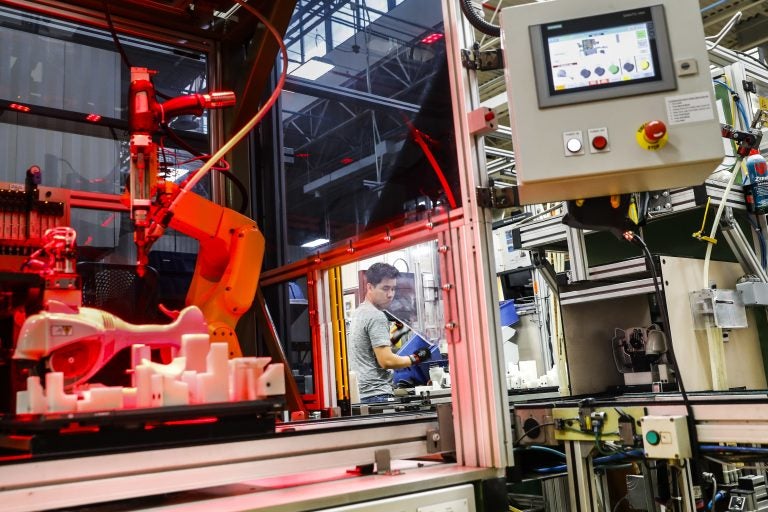

In this Thursday, May 25, 2017 photo, an assembly line laborer works alongside a collaborative robot, left, on a chainsaw production line at the Stihl Inc. production plant in Virginia Beach, Va. (John Minchillo/AP Photo)

In the past few years, researchers have published report after report after report on how many jobs robots will take over in the future.

Another new report, this one from the management consulting firm McKinsey & Co., says that in the next 10 years, more companies could automate the work done by humans now, but that not every place in the United States will be affected equally.

Philadelphia is expected to come out quite well: The McKinsey researchers project more demand for jobs related to health care and technology, and the city is well placed to meet that demand with its medical centers and universities.

More routine tasks such as bookkeeping and office support could be done by software or artificial intelligence, so there will be some job loss, but ultimately there should still be job growth in Philadelphia, unlike other places around the country.

However, there have been 18 reports in recent years trying to anticipate how many jobs automation will create or destroy. MIT Technology Review has tracked all these estimates — and the predictions differ by millions.

Susan Lund, a partner at McKinsey and co-author of the latest report, is aware of this: “We’re not forecasting what’s going to happen, we look at a range of different adoption rates.”

She explained that the McKinsey report mapped out three possible futures — from 4% of all work tasks being automated by 2030, to 42% of work being automated.

Daron Acemoglu, an institute professor of economics at MIT, also studies how automation affects the labor market.

“When we’re talking about automation in the future, we’re talking about AI,” or artificial intelligence, Acemoglu said. “Nobody knows what AI is going to be capable of in 10 years time. If people make some categorical statements about AI is going to do this, AI is going to do that … you should just immediately hang up the phone.”

He said he agrees with the McKinsey report’s conclusion that different places across the U.S. will feel the impact of automation differently, but he added that it’s not a new finding.

Acemoglu studied what happened in the U.S. from 1990 to 2007 as more companies started using industrial robots, like robotic arms in car factories. He found that the number of workers who lost their jobs because of robots was relatively small — for every 1,000 workers, introducing one robot meant a 0.2 percentage point drop in employment-to-population ratio, which measures how many people are working out of the total working-age population.

And contrary to predictions from other automation reports, Acemoglu found that automation is more likely to affect middle-age workers, not older workers. He said industrial robots do production work on the factory floor, which is usually done by middle-age workers. Older factory workers typically have moved on to non-production or supervisory jobs.

Trying to figure out how quickly automation technology will develop and be adopted in the future is harder than experts anticipate, Acemoglu said.

James Bessen, an economist at Boston University who also specializes in studying the impact of technology and automation, said the U.S. needs to collect more data on automation.

He did a recent study in the Netherlands because it’s one of the few places in the world with detailed data on the firm-by-firm level on the impact of automation going back to the 2000s.

Like Acemoglu’s, some of Bessen’s findings did not match what people had predicted. For instance, reports usually predict that robots will replace low-wage workers. Bessen found that there is no significant difference in whether a low-wage or high-wage worker will leave a company because of automation.

“It’s really across the board in terms of skill levels and wage levels at least, so that leads me to question how realistic some of these … projections are,” he said.

Other researchers have also argued that the United States needs to collect better data to fully understand the impact of automation. Bessen points out the U.S. Census Bureau is starting to do this: The 2017 Economic Census included questions on how much companies used tech such as machine learning, robotics, and automated retrieval systems.

Yet other researchers are moving forward by coming up with new ways of studying this issue altogether. Mark Muro, senior fellow and policy director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution, said he sees all the predictive reports as “initial stabs at raising the kinds of things we need to be thinking about.”

He recently co-authored his own report on the impact of automation using a model developed by McKinsey. But he is also working with researchers at Stanford to find out how much the text in patents for artificial intelligence overlap with the text in job descriptions, to see if that gives a better sense of which jobs can be replaced by machines.

That report is scheduled for release in October.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.