Why the head of the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium decided to get vaccinated

Dr. Ala Stanford has had the virus and thought she’d wait for natural antibodies to protect her. But she realized others would only see what she wasn’t doing.

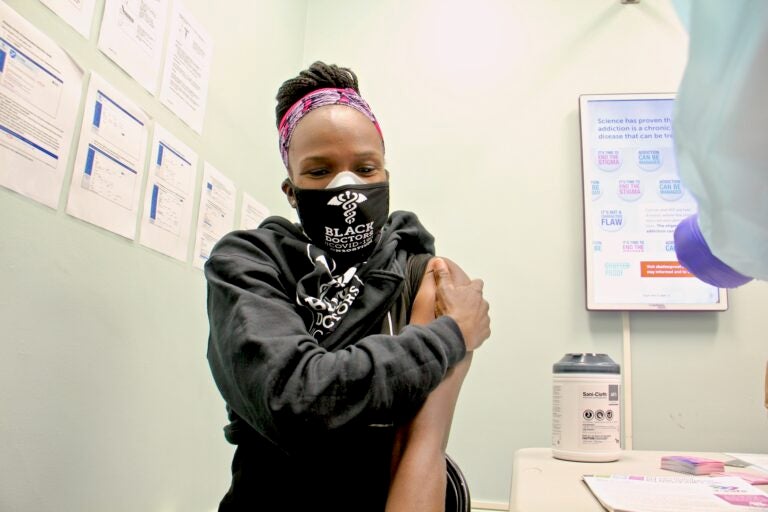

Dr. Ala Stanford gets her COVID-19 vaccination at a Philadelphia Department of Health clinic on Dec. 16, 2020. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Updated Jan. 8

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the current surge?

Dr. Ala Stanford is usually on the giving end of medical treatment, but on Wednesday afternoon, she played the rare role of patient as she received her first dose of the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine.

This was not the original plan.

As recently as 72 hours ago, Stanford wasn’t going to get the vaccine. At least, not right away. She tested positive for COVID-19 in August and wanted to let her natural antibodies do the work of protecting her from getting sick again. She made an agreement with her physician that she would test regularly for antibodies, and once they wore off, she would get the vaccine.

But the surgeon soon realized that her personal decisions no longer exist in a vacuum. Stanford started the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium in April in response to what she saw as a lack of affordable, barrier-free testing for African Americans in and around Philadelphia, among the hardest hit by the virus. What started as a scrappy group of physicians in a rented van popping up to test people on street corners and in church parking lots became a well-oiled operation that secured a testing contract with the City of Philadelphia and has performed more than 20,000 tests to date.

The consortium was valuable not just in providing access to COVID testing for Black Philadelphians who might not have insurance, a car, a doctor’s note or symptoms. It also became a source of trusted medical care for many Black people who were wary of going to government-run health sites.

As a result, Stanford has, in a sense, become the face of the COVID-19 response for the Black community in Philadelphia. That became abundantly clear to her over the weekend, she said, when she was out testing people in West Philadelphia.

“There were many people that said, ‘Doc, we really appreciate what you’re doing, when you tell me to get that vaccine, I’m gonna roll up my sleeve,’” Stanford said. “I feel like I heard that 100 times.”

She said she realized that not everyone had access to the regular antibody testing that she planned to do. Her mother wouldn’t get the vaccine if she didn’t. Neither would her husband’s mother.

“My reasoning for not taking it wasn’t going to resonate with people,” Stanford said. “All they were going to hear was, Dr. Stanford’s not going to take the vaccine.”

Stanford knew the research showed the vaccine was safe and effective. Side effects were usually mild. She knew there were still unknowns, like whether it’s safe for those who are pregnant, or for children, or how long immunity will last. Mostly, she worried about the long-term impact that new technology may have years down the line, but also knew that for Black people, COVID could be deadly a lot sooner than that.

She prayed about it, cried about it, and did her research. When she showed up to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health vaccine clinic on Wednesday afternoon, she was still nervous, but resolved in her decision.

She gave an attendant at the front desk her personal information, registered in advance for her second dose, and waited for her husband to do the same. Surrounded by masked members of her team, she walked down the hall to the room where she received her first shot.

When she came back to the lobby, she had tears staining her cheeks and a smile on her face. In the hallway, she’d run into another woman who’d just been vaccinated, and her eyes welled up with tears.

“I knew that she must have felt what I felt,” Stanford said. “Wanting to do it, but being afraid. But not letting the fear overtake the knowledge and the faith that we’re moving on to better days.”

Stanford got her second dose of the vaccine the week of Jan. 4. Like others who have received their second doses, her side effects were more severe this time, Stanford said in an Instagram post.

‘If you’re not taking it, I’m not taking it’

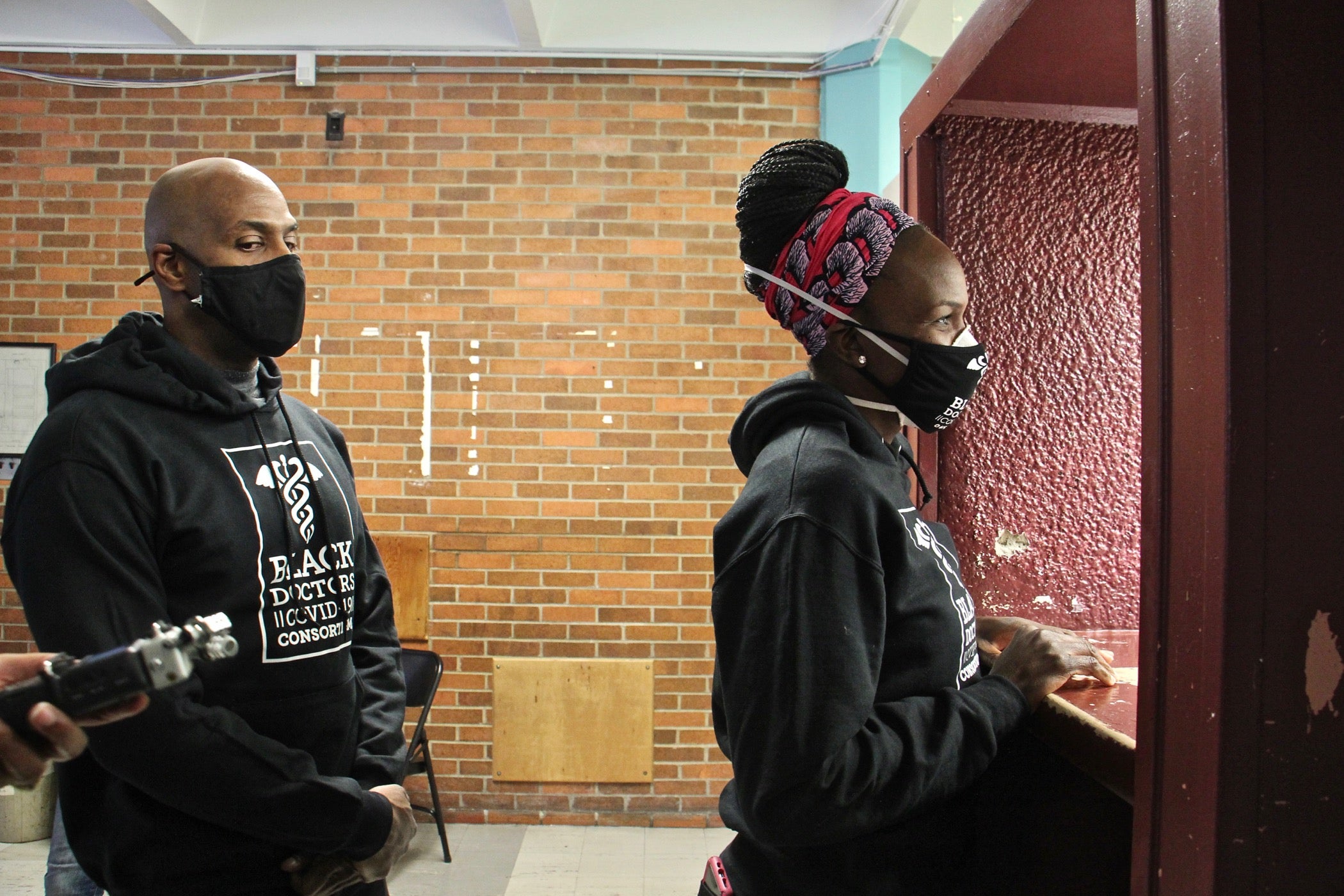

Stanford’s decision cast a ripple effect through the consortium.

Cynthia Taylor is a retired chemist who works with the group, doing administrative work and acting as an assistant to Stanford. Until a couple of days ago, she was also a “firm no” on the vaccine.

Learning Stanford wasn’t planning to take it sealed the deal for Taylor, who was already leaning in that direction.

“I understand we’re all different and we all have different situations,” she said, “but if you’re not taking it, I’m not taking it.”

Taylor and her husband, a police officer, both tested positive for the coronavirus in November. She had no symptoms, but her husband felt chills, had a cough, and felt achy. She said his symptoms lasted nearly a month, and he still has not regained his sense of taste or smell.

“This is a scary virus, and there’s still so much we don’t know,” Taylor said. She explained that it is this fear of the unknown that made her wary of the vaccine.

“How do you create a vaccine for something when there’s still things we don’t know? That’s my fear. We don’t know.”

But, she said, it was Stanford’s encouragement to weigh the risks and benefits that got her to reconsider. She doesn’t want to get COVID-19 again and risk being too sick — or worse — to continue helping the people she’s been able to offer testing. That, plus pages and pages of research that Stanford printed out from the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, changed her mind.

“This is bigger than just us in this room,” Taylor said. “It’s bigger than Philadelphia. It’s about the world coming back together and us having a semblance of a life again. I feel like the next phase is starting.”

After she got her shot, Taylor reached into her pocket and pulled out the hot pink sticker noting she’d received the vaccine.

“I’m saving it to put it on my coat,” she said. “So that everyone can see.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated to include Stanford’s experience with the second dose of the vaccine.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)