Why Cape May is such a good place to see hawks

-

-

-

Richard Crossley uses MULTIPLE PHOTOS of birds (sharp-shinned hawks here) in his bird identification books. (Photo by Richard Crossley/Crossley ID Guides)

On a recent summer afternoon, Pete Dunne stood on the wooden hawkwatch platform at Cape May Point State Park, Swarovski binoculars around his neck. Along with the small group of birdwatchers who’d congregated around him – a typical occurrence — he looked out over Bunker Pond, a freshwater pool surrounded by bayberry bushes, red cedars and cherry trees. Passing over the pond, he explained, was a peregrine falcon.

“You sure are a walking encyclopedia about these birds, guy,” one man said.

Or, as the Wall Street Journal once put it in a personality profile, Dunne is the “bard of birding.” He’s written 20 books on the subject, and brought international attention to Cape May as a birdwatching destination. The Cape May Bird Observatory and the hawkwatch platform are both celebrating their 40th anniversary. The hawkwatch deck was something Dunne dreamed up to help count birds.

Ranked among the best hawkwatching spots in the world, the platform is home base for Cape May’s annual hawk count, which kicked off Sept 1, 2016.

It’s a three-month affair run by the Cape May Bird Observatory and sponsored by Swarovski Optik. Biologists will work from dawn to dusk tallying migrating hawks from 18 species, while other CMBO naturalists stationed on the platform educate the public. By October, the stand will frequently be at max capacity, approximately 200 people. Visiting birders – who may be speaking English or French or Dutch or Hebrew — will range in age from five to 105.

Birds bring business

All this counting translates into big business. While the Cape May County Department of Tourism is currently updating its economic impact report, recent data suggests eco-tourism brings $639 million to the county each year. Twenty-five percent of visitors participate in nature-based activities, with 11% focusing on birding.

According to Diane Weiland, Director of Tourism: “The hawkwatch is a must-do on the birder’s calendar.”

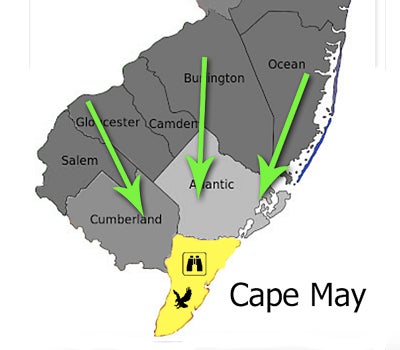

The funnel

Many avian species are wary of flying over vast expanses of water, since having nowhere to hide makes them vulnerable to predators. So, because of the peninsular configuration of New Jersey, birds traveling south along the coast are funneled to the tip of the state, aka Cape May. This makes the island an ornithological hot spot. Migrating hawks — a vague term for large, flesh-eating birds that capture prey from an elevated location – do well feeding on smaller species here. Falling under the hawk umbrella are eagles, ospreys, and falcons.

Many avian species are wary of flying over vast expanses of water, since having nowhere to hide makes them vulnerable to predators. So, because of the peninsular configuration of New Jersey, birds traveling south along the coast are funneled to the tip of the state, aka Cape May. This makes the island an ornithological hot spot. Migrating hawks — a vague term for large, flesh-eating birds that capture prey from an elevated location – do well feeding on smaller species here. Falling under the hawk umbrella are eagles, ospreys, and falcons.

As early as the 1931, wardens from the Association of Audubon Societies were stationed along Sunset Boulevard in order to tally these hawks and make sure hunters weren’t shooting too many. In the Depression era, these large raptors were killed for sport and also for food. Then, when environmental regulations put an end to the practice, volunteers continued tallying. That’s largely because hawks serve as canaries in the metaphoric coalmine — they rank high in the food chain, meaning their numbers are a window into the health of the entire pyramid.

One bird, two bird….

Dunne came to Cape May in 1976 as a 24-year-old employee of CMBO, then an experimental startup of the New Jersey Audubon Society. His job was to count migrating hawks for eight to 12 hours a day, seven days a week, September 1 through November 30. For this, he earned $500 via a grant from the state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Dunne’s first day on the job, he identified the park as the best space for viewing, and climbed on top of a four-foot, sawed off telephone pole for a better vantage point over the reed grass by the pond. While he managed for the day, he realized how hard this would be to keep up for three months, and spent the evening building a three-foot-by-four-foot table out of plywood and two-by-fours. He worked by the headlights of his white Volkswagen bug.

The then-superintendent of the park was not thrilled with this makeshift command post. “He asked that I take the table with me at the end of every day,” Dunne said. “But it was a heavy son of a bitch – it weighed more than 100 pounds. He settled for tipping it on its side so no one else could climb on top.” That season, only 20 people, one of them Dunne’s girlfriend, stopped by the park for hawkwatching.

By the following year, Dunne had taken over as Director of CMBO, but he didn’t want to give up counting hawks. He borrowed a lifeguard stand from the Cape May Point Beach Patrol, and this served as his platform for three seasons. Then, the Cape May Point State Park – by now fully supportive of Dunne’s work – had a new, 50-foot platform built. To this they soon added another 50 feet. Eventually, as interest increased, they demolished the original iteration entirely, and built the multilayered structure that stands today. In 2015, over 20,000 hawkwatchers came to the park.

While Dunne has birded all over the world, from east Africa to the Amazon basin, his most memorable experience happened on this platform, on October 4, 1977, when he broke the record for most sharp-shinned hawks spotted in Cape May in a single day: 11,096. It’s the twelve-hour period that earned Cape May the title of world raptor capital.

While Dunne has birded all over the world, from east Africa to the Amazon basin, his most memorable experience happened on this platform, on October 4, 1977, when he broke the record for most sharp-shinned hawks spotted in Cape May in a single day: 11,096. It’s the twelve-hour period that earned Cape May the title of world raptor capital.

“It was sunny,” he said. “But the sky was so full of hawks, the burn factor was probably a two.”

Why Hawks?

While birding may have a reputation as the hobby of a genteel, retired set, watching hawks can be an exciting – sometimes harrowing – experience, especially when a falcon decapitates its prey mid-air, which you might see anywhere from 12 to 20 times over the course of a season on the platform.

“Some birds have a bill specially designed to snip a cervical membrane,” Dunne said. “There was one day we had a cuckoo fly right in front of us, and right on its tail was a merlin. The cuckoo opened its mouth and screamed, and the merlin just sucker punched it. We all felt so guilty. But of course, we were cheering for the merlin. We’re all hawk people. They’re fast, they’re powerful, and they just push our buttons.”

Take the peregrine falcon which, when divebombing for dinner at 200 miles per hour, outpaces the cheetah as the fastest animal on the planet. She can easily carry a 13-inch flicker, a particularly beefy woodpecker, away in her talons. Or the bald eagle, which is the second largest bird of prey in America and, according to some, a pirate – it’s been known to steal live fish from the talons of an osprey, because this is easier than fishing itself. It’s the reason Benjamin Frankly fought against awarding this hawk it’s designation as America’s national bird.

Part of the fun for hawkwatchers is picking a favorite. For Dunne, that’s the northern harrier. While most birds of prey have great speed and strength and, therefore, don’t need much brainpower, the norther harrier is an intelligent species.

“I used to do surveys,” Dunne said. “I’d try to find their nests in my car. After one season, they recognized my car, and would no longer lead me to them. I discovered this only when I cracked up my own vehicle and had to borrow a friend’s. Suddenly, the birds were going back to their nests. They’ve definitely got a brain.”

To see these creatures up close, you can attend a banding demonstration conducted by the Cape May Raptor Banding Project every Saturday and Sunday morning at the Cape May Point State Park, from mid-September through October, at 10am.

Flight risks

A good season on the hawkwatch platform today translates to between 40,000 and 50,000 birds. Thirty years ago, a good season was somewhere between 180,000 and 190,000.

While none of the hawks who migrate through Cape May are currently endangered species – thanks largely to the conservation efforts of organizations like CMBO — several of them do have moderate watch scores, according to the North American Bird Conservation Initiative. This means further habitat destruction could be devastating. Wind turbines, utility lines, even the plate glass windows of residential homes pose threats to migrating hawks, as the birds fly into these things and suffer brain hemorrhages. Additionally, the birds are killed when household rodenticides poison their prey.And yet Dunne, now an ambassador for New Jersey Audubon, feels optimistic about the platform’s next 40 years.

“When people come up here, the natural world becomes real,” he said. “People become bonded to it, they develop a sense of intimacy, and they become protective. When it comes to self-preservation, we’re not the brightest species, but I think most people are getting the idea – the earth is dynamic, and we have the power to drive that change, for better or worse. Nobody wants to lose what we’ve got: the Grand Canyon of birdwatching, here in Cape May.”

A celebration of the platform’s 40th anniversary, which coincides with CMBO’s 40th anniversary, will take place from October 20 to October 24, and will include panel discussions, dinners and pelagic birding trips. For more information, visit njaudubon.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.