Who owns the streets of Philadelphia? It’s complicated…

Who owns the streets of Philadelphia?

If you were like me, you would probably say, “Bruce Springsteen” and grin smugly, as though this wasn’t the millionth time someone made that exact same joke.

And you would probably be wrong, or at least not entirely right. For musicians signed to a label, ownership of any given song’s intellectual property rights can be split a dozen ways. While I don’t know the specifics of Bruce’s deal with Columbia Records, who released the Philadelphia soundtrack, it’s likely that Columbia, Springsteen, TriStar, and Springsteen’s two co-producers on “Streets of Philadelphia” all have some royalty rights.

As for the song’s namesake slabs of asphalt and concrete, life imitates art. Ownership of Philly’s straightforward grid of avenues and alleys is far more complicated than it seems.

No fewer than nine government and quasi-governmental agencies (plus a few private entities) are responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of Philly’s roads. Then there are the utilities, telecom companies, adjacent property owners, and neighborhood associations, who all have varying levels of rights to and responsibilities. Add a complex overlay of funding schemes and oversight regimens, and the street ownership map gets downright byzantine.

But it’s a complexity not without cause: dividing responsibilities allows for specialization, which can make for more effective oversight of Philadelphia’s 2,575 miles of public pavement.

But the system only works if all the different actors can get on the same page, something that gets more difficult as the cast grows. Like other areas of government, effectively managing the complicated streets system requires a strong director, something Philadelphia hasn’t always had.

THE STRAIGHT AND NARROW

Streets aren’t inherently complex.

In the grand scheme of human engineering feats, the lowly road doesn’t quite rise to the level of towering skyscrapers or massive bridges. This isn’t to say that streets aren’t important. Like fist-pumping bros at a Jersey Shore nightclub, city streets are simple, yet economically vital.

The steps for creating a street are few, and the process hasn’t changed much since modern asphalt concrete was invented in 1870. Level some ground. Pour some crushed rock or concrete as a foundation (optional, but recommended). Apply a few layers of asphalt. Wait a few hours. Paint traffic lines, and call it a job well done.

But the way nature abhors a vacuum, bureaucracy abhors simplicity, and so recondite legal concepts and baroque organizational structures are built upon something as pedestrian as the ground we walk on.

Complexity itself is not necessarily a bad thing. Complex systems can operate more efficiently and effectively than relatively simple ones. Ordering a burrito from Chipotle is a multi-step, multi-person process, but it’s still faster and more delicious than ordering a BigMac. Governance is no different.

Multiple, specialized agencies can deliver tailored services, but coordination efforts between them represent real transaction costs. When those transaction costs are minor, they cause delays. That’s why resurfacing a street can take a few weeks – it’s a matter of the Philadelphia Streets Department getting utility companies to inspect their manhole covers for defects before pouring fresh asphalt. The costs of those delays are minor (annoyingly bumpy rides on the milled roads for a few weeks) and externalized (borne by local residents), so it doesn’t make a lot of sense for either the city or the utilities to spend a lot of time and effort stepping up the coordination efforts.

And the bigger the coordination costs get, the more likely a temporary delay turns into permanent deadlock, killing worthwhile projects. As agencies proliferate, the need for a coordinating director to step in grows.

SERIOUSLY, WHO THE HECK OWNS THE STREETS?

Responsibility for maintaining and overseeing Philadelphia’s 2,235 miles of roadway is split among the Philadelphia Streets Department, PennDOT, the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department, the Delaware River Port Authority, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation, the Pennsylvania Housing Authority, Philadelphia International Airport, the Burlington County Bridge Corporation, SEPTA, and a number of private entities.*

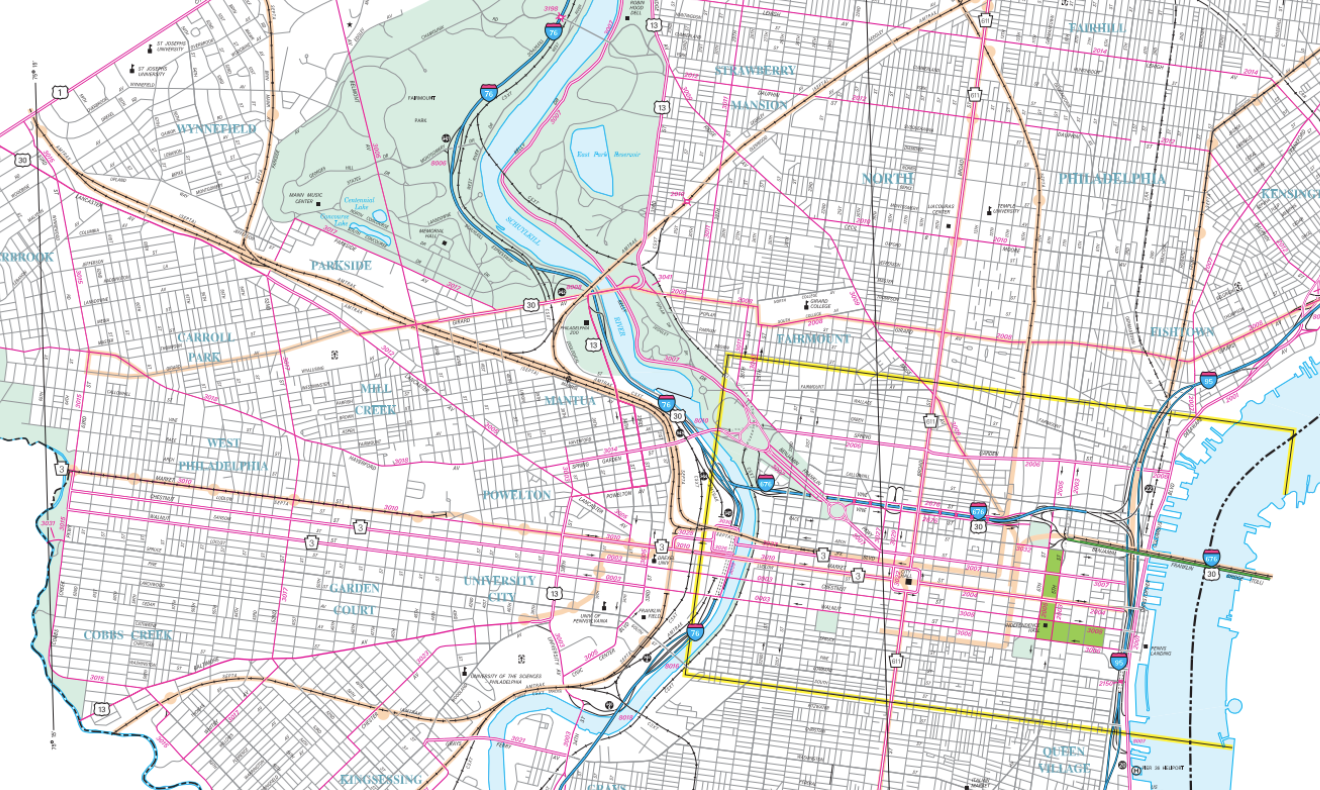

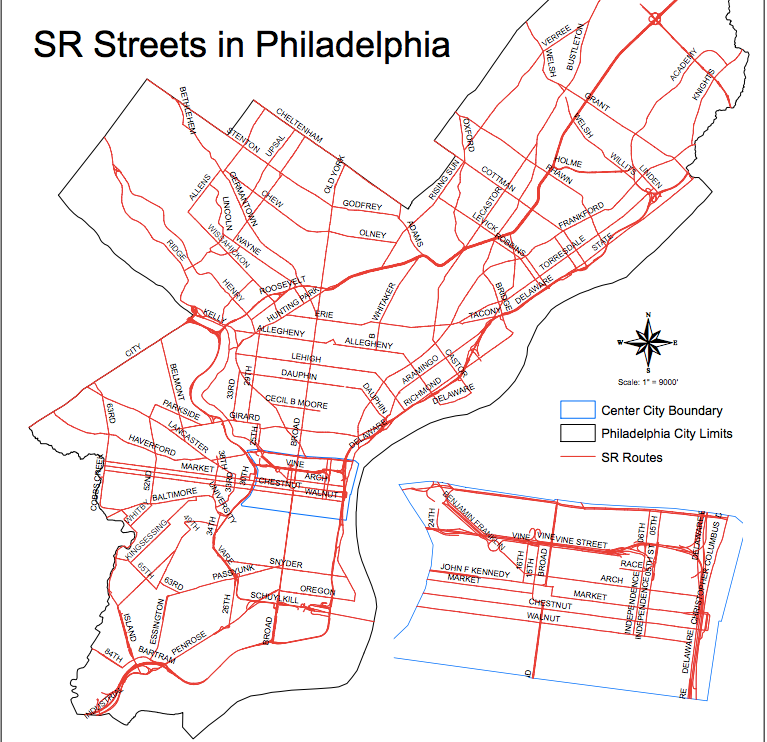

In the photo below (click here for a larger version; make sure you zoom in), the blue lines are interstate highways (e.g. I-76), which are under PennDOT’s control. The green lines are DRPA’s bridges and the roadways leading up to them. Pink lines are other state-maintained highways and traffic routes. Everything in gray is a city street. (Here is another map, showing just the state routes, and a list of the state controlled roads.)

While some major roads make intuitive sense, a closer look reveals all sorts of odd splits in responsibility. West Passyunk is a state road, but the city controls East Passyunk. Ridge Avenue stops being PennDOT’s headache once it hits Spring Garden. Fifth and 6th Streets are PennDOT’s responsibility between Spring Garden and Walnut, but that’s it. Most of the major streets that connect Philadelphia to surrounding suburbs are under PennDOT’s purview, but so are some, like Allegheny Avenue, that never so much as get close to crossing the city’s limits.

On the map above, the Navy Yard appears to be road free, the Yard’s 15 miles of PIDC-controlled thoroughfare just aren’t shown. PHL operates 3 miles of roadway, too, and the housing authority has 7 miles. And another 57 miles of streets with a public right-of-way are controlled by various private entities.

The streets running through Fairmount Park are all controlled by Philadelphia Parks & Rec, meaning the upkeep costs come out of their budget, not the Streets department. But about 9 of those 48 miles are also state routes, meaning the Commonwealth pays for them. That’s why it’s accurate to say there are 503 miles of state highways in Philadelphia, and that PennDOT controls 494 miles of Philly pavement.

The DRPA and the BCBC control the bridges over the Delaware and some of the stretches of highway leading up to them. The BCBC operates the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge, and the DRPA runs the Benjamin Franklin, Walt Whitman, Commodore Barry and Betsy Ross Bridges.

SEPTA is solely responsible for a half-mile of roadway, but that figure conceals the full extent of SEPTA’s street control.

On any street with trolley tracks, including tracks that were long ago paved over (but not removed), SEPTA is responsible for maintenance of the pavement between the tracks and eighteen inches on either side. SEPTA must fill potholes close to Route 15’s tracks on Girard Avenue, and along the “suspended” Route 23 trolley route. But it also handles potholes on streets where only longtime residents remember trolleys, like Walnut Avenue and 7th Street.

JUST SCRATCHING THE SURFACE

If Philly’s highways and byways were just split a few dozen ways, then things wouldn’t be all that confusing, even with SEPTA’s sometimes hidden obligations. But our trip down this windy road of overlapping ownership has just begun.

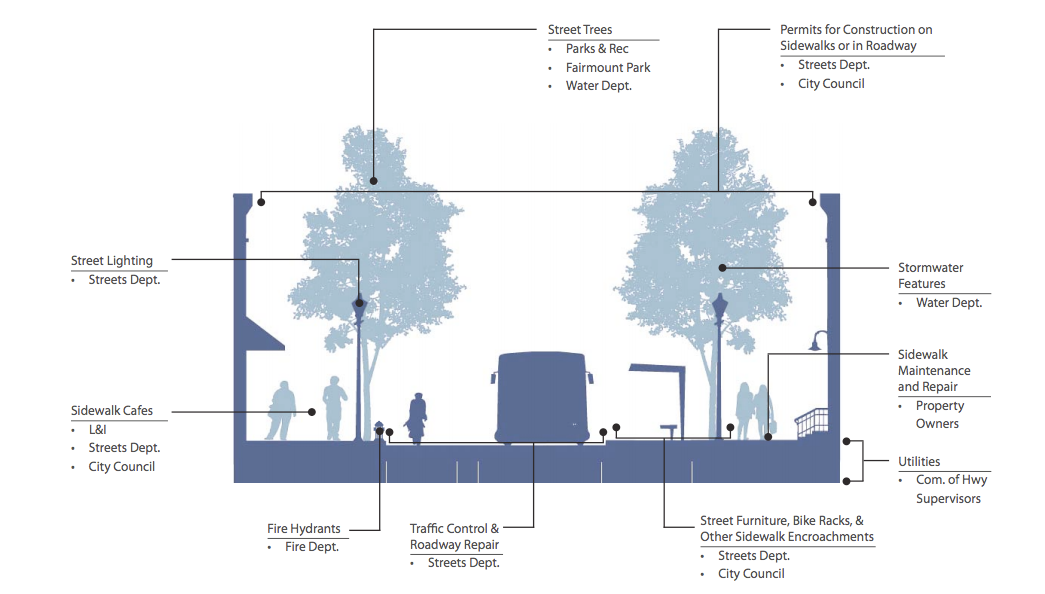

When traffic engineers and city planners talk about “streets” they don’t mean just the paved traffic lanes and parking lanes– that’s the “cartway.” A street includes the sidewalk and curbs – it’s the entirety of the public right-of-way.

And in the technical argot, “right-of-way” doesn’t mean who gets to go first at a four-way stop. Rather, it’s a specific kind of easement, allowing for public access to the cartway and sidewalks.

Generally, easements provide someone a right to use or access someone else’s property in a specified manner. Think of a sidewalk in front of house. The homeowner owns the land in front of her house up to the curb, but the public has a public access easement to that sidewalk. They can walk there, but that’s about it; the easement doesn’t mean you can build a stand on that sidewalk.

So “who owns the roads” is a bit of a misleading question. The streets themselves operate as public rights of way over stretches of Philadelphia that happen to have a bunch of different owners. In most of Philadelphia, the city itself owns the land underneath the streets, including most (but not all) of the state highways.

On your average 50-foot-wide city street, you’ll have a 12-foot sidewalk, a 26-foot cartway, and another 12-foot sidewalk. The cartway pavement is usually maintained by the Streets department (unless of course, it’s a state highway or there are SEPTA tracks). In many parts of the city, the property lines for the adjacent lots extend to the sidewalk curb. That means the maintenance responsibilities for the sidewalk and curb fall on the property owners – that’s why you need to shovel snow from your sidewalk or pay to replace a crumbling curb. But due to the public right-of-way over the sidewalk, property owners still need to seek permits to build on or do any other major work on the sidewalk.

In some parts of Northeast and Northwest Philly, the right-of-way extends beyond the sidewalk, onto front yards.

In other parts of town, including many of the row home neighborhoods, the property line ends where the sidewalk begins. However, city laws still require those property owners to maintain of the sidewalk and curb.

THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD

Until 1951, Philadelphia’s streets were under the purview of the Department of Public Works, which was also home to the gas, water and lighting bureaus. It was a one stop shop for most city functions, which made planning easy. But as the engineering behind functions like water management and traffic control became more complex, the need for focused departments with more singular missions grew.

With the adoption of the Home Rule Charter, public works was split into Departments of Streets, Water, Public Property, and Commerce. With the split, oversight on a project like digging up a street to replace a water line jumped from one agency with one supervisor to two.

In the 1960s, the city entered into an agreement with PennDOT for the creation and maintenance of the state highway system in Philadelphia. Ever since, PennDOT has been responsible for the cartway on state routes, and where a state route intersects with a city road, PennDOT retains responsibility over the road.

However, the rest of the right-of-way remains under city control, with Streets handling the signs, signals and traffic lights, plus the sidewalks – except for the interstate highways, though. There, PennDOT’s responsible for nearly everything, except for the lands alongside and underneath I-95, which are owned by a non-profit joint venture between the city and state called the Interstate Land Management Corporation.

In 1968, SEPTA, a Frankenstein’s monster of government agencies and private transit companies that started going bankrupt in the 1960s, assumed control of the Philadelphia Transportation Company’s bus and trolley system. And with the tracks came PTC’s responsibility to maintain pavement around them.

And so, at the intersection of a city street like 3rd, and a state street like Walnut, you can have SEPTA responsible for the middle of the road where a trolley once ran, PennDOT in charge of the edges of the travel lane, and Streets controlling the sidewalks, lights and signs.

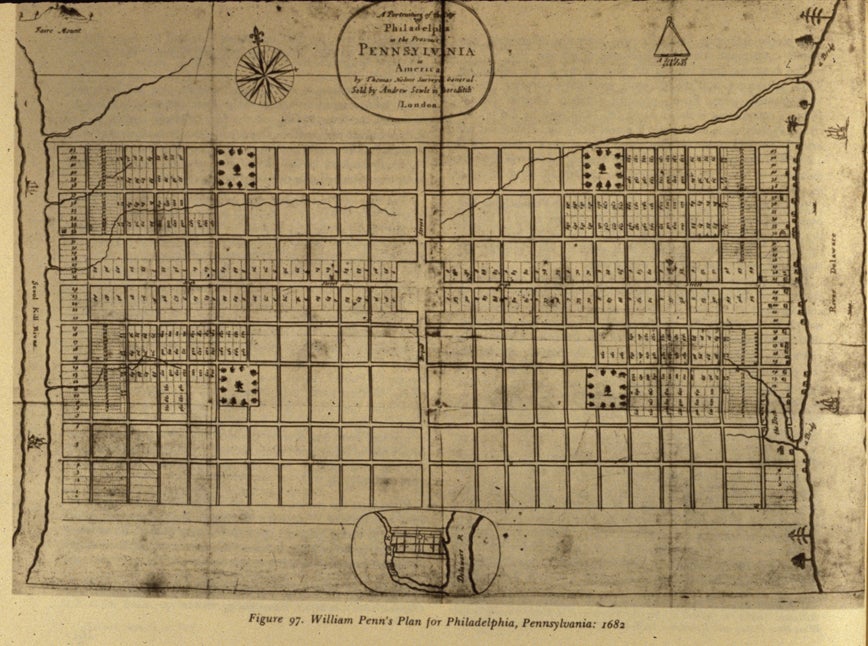

William Penn’s original plan for Philadelphia’s streets, a grid, was revolutionary in its simplicity. It was the first time a city was laid out in a set of orderly blocks, a design copied by nearly every town since.

Penn’s original design called for wide streets at regularly placed intervals connecting stately manors, but soon enough private landowners started subdividing their lots to squeeze upwards of twenty row homes where one house might have stood, and building narrow alleys, like Elfreth’s, for access. As Mary Maples and Richard S. Dunn wrote in Philadelphia: a 300-year History: “Soon dozens of other alleys appeared throughout the city, making Philadelphia one of the most congested communities in America, in utter violation of Penn’s dream of a green country town.”

Soon after, even on the city owned streets, citizens were taking matters into their own hands, as merchants voluntarily paid to lay down cobblestones and pavers on the streets in front of their businesses. It wasn’t until 1762 that the city took over paving and street cleaning, paying for both with lotteries. After Philadelphia was finally incorporated as a city proper in 1789 (it operated under a colonial charter before), its ability to levy taxes was deemed woefully inadequate. So a year later the state assembly provided the newly incorporated City of Philadelphia with a taxing authority “for the purposes of lighting, watching, watering, pitching, paving, and cleansing the streets, lanes, and alleys of the city.”

But even after then, the building of paved toll roads, marked by a horizontal pike that turned on a vertical pin to allow horses and carriages to cross after payment, to cities like Baltimore, Lancaster and Germantown were handled by private corporations named after their destinations. The private companies – by 1832, 220 turnpike companies had been chartered in Pennsylvania, building around 3,000 miles of roads across the state – ignored Penn’s original grid in favor of more direct routes to their destinations. Those routes, eventually turned over to the government, later became Baltimore, Lancaster and Germantown Pikes, and then later still, Avenues.

Fast forward a few centuries and now pretty much anything that happens in the right-of-way requires the city’s signoff, regardless of who owns the land, says Darin Gatti, chief engineer at Streets. “Whether in the air or underground, if you’re in the right-of-way, you need some sort of approval to be there.”

For utilities, the city enters into agreements for occupying the right-of-way with their underground pipes, wires, and sewers; street level manhole covers and utility boxes; or utility poles above the streets. And whenever work has to be done that alters or shuts down a street, permits are required.

The utilities don’t pay rent to occupy the right-of-way – a cost that would get passed on to consumers – but they don’t get much security, either. Whenever the city decides that a utility has to move – like when it rebuilds a bridge that carries electricity lines along it – the utility has to move it and at no cost to the city.

And any given street can have a dozen of utilities operating in the right-of-way. The Water Department will have water lines and sewers underneath, along with telephone, gas and power lines. According to Gatti, fiber optic cables are taking up more and more space, to the extent that it’s getting hard to fit it all underneath the streets.

And in case all this wasn’t confusing enough, there are exceptions to nearly everything written above.

With dozens of entities overseeing their own, specific parts of Philadelphia’s thoroughfares, it’s easy for any one agency to lose the forest for the trees.

RULES OF THE ROAD

As I alluded to before, government and burritos are similar beasts: messy, overstuffed, great when good, awful when bad.

When you order a burrito from Chipotle, where upwards of four employees might take part of your order, the efficiency gains from the specialized division of labor disappear when a customer tries ordering for two. That person has to repeatedly ask their companion what they want on their burrito. It jams the whole line up.

To be efficient and effective, the ordering system requires a centralized decision maker coordinating between the various burrito-building departments, to oversee the big bean decisions and salsa selections. And splitting a burrito between two people becomes a literal and figurative mess, requiring meat choice negotiations and political give-and-take on how to allocate guacamole investment costs.

So it is with streets. Splitting the Department of Public Works into a Streets Department and a Water Department allowed for the employees at each to specialize in their fields and provide more specialized services; it effectively added new choices to our infrastructure menu. For a city of our size, such a move was necessary and inevitable, said Gatti.

But that split means that a project that once needed one agency’s signoff now requires two.

When agencies’ interests line up, that’s easy. But when agency goals differ, you have a recipe for recrimination and deadlock. Splitting a burrito is easy if you have the same tastes; it’s harder between a skinflint and someone who’ll pay anything, even $2.05(!) for a lousy scoop of guacamole. And when the head of an agency is incompetent – someone “trying to eat gluten-free” in our burrito allegory – then the situation is hopeless.

In transportation, we have a bunch of different government agencies, quasi-governmental entities private actors all trying to split a boulevard burrito. The 3rd and Walnut intersection is split between a statewide department (PennDOT), a regional authority (SEPTA) and a city agency (Streets), each with a different constituencies, different goals and different budgets.

And depending on the personalities at the top of each, these agencies can get along like doting sisters or fight like the Gallagher brothers. And when you add in the other involved parties, like nearby property owners, neighborhood associations, utilities and planning commissions, you get one big, maybe dysfunctional, family.

Throw on the complicated funding streams for any major project, and my Chipotle metaphor falls apart like a soggy soft taco, because the reality is just too convoluted for that, and because no one really wants to read asinine similes like: “You can think of the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act as a specialized sour cream only fund, administered by the second oldest half-sibling, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, who decides who gets that sour cream (i.e. multi-modal trail study and engineering funds) based off rock-paper-scissors, which here means a quasi-technical, quasi-political process featuring multiple investment horizons.”

If a streets project wants to use federal funds, then it usually needs to seek approval from the DVRPC, unless it can apply directly for a specific grant. Removing a lane from the cartway means a City Council vote. Almost every change of consequence means months or even years of planning sessions among all the stakeholders named so far, plus neighborhood associations and commercial district corporations.

And it doesn’t help when many of the actors involved have completely unrelated missions. The Water Department doesn’t really care about traffic on your street when it has a century old sewer to replace.

HEADING THE RIGHT WAY

Philly’s city streets aren’t unique when it comes to these questions and issues, which bedevil all areas of government. How to cajole, convince or force others to endorse some policy prescription is the art of politics.

This convoluted system works when it results in technically advanced improvements, like some of Water Department’s green stormwater management infrastructure improvements.

But the system fails when worthy projects are sidelined or derailed by a failure to get all the necessary parties on board. If PennDOT and Streets can’t cooperate, then everyone suffers.

Interagency spats are merely annoying when they’re over who pays to fill a pothole, but they can have massive, long lasting impacts on the city’s development.

During the Great Depression, Philadelphia’s Republican city leaders vociferously opposed the New Deal’s recovery programs. FDR still paid for 31 projects in Philadelphia, including treasures like the Main Post Office, Central High School and Bok Technical School. But the city could have had dozens more: New York City had 440 New Deal-funded projects, San Francisco received 319, and Chicago enjoyed 98. Even Fort Worth, Texas outpaced the then third-largest city in America, with 37. Philadelphia’s inability to play well with other governments cost the city dearly.

A few years later, with reformer Joe Clark sitting in City Hall and Ed Bacon leading the charge, Philadelphia managed to tear down the Chinese Wall, creating Center City as we know it today. That required huge amounts of coordination among city, state and private actors. Bacon’s leadership, and his ability to corral the angry herd of developers, planners, city officials, state politicians and angry neighbors, made him nationally renown and is why he’s sometimes called the Father of Modern Philadelphia (and Kevin).

When Philly’s leaders managed to work together, impressive results followed; when they couldn’t, the city suffered. These possibilities come and go everyday without notice, but a few dramatic examples highlight what’s at risk, like the proposal to cap I-95 to provide better access to the Delaware waterfront.

Economic consultants estimate that covering I-95 with a park near Penn’s Landing would generate $1.8 billion in economic growth for a cost of $250 million. Assuming the forecasts aren’t horrifically wrong, burying the highway is the only economically rational decision.

If the cap-or-no-cap decision – and all the costs and benefits it would generate – rested in the hands of just one entity, it would happen. A private company that was offered a 7.2X return on investment like this would find investors and lenders. But like so many other streets, there are multiple interests at play here, and multiple decision makers who all need to get on the same page.

The study was conducted by the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, which exists to promote the waterfront. It would require PennDOT – tasked with the ensuring safe and fast travel in Pennsylvania, not economic development – to get behind it, the DVRPC to OK federal funds, the city to chip in. It would disrupt the flow of interstate commerce and snarl daily commutes for years, and it will cost taxpayers hundreds of millions.

It would be worth it for the regional economy, but while the costs would be borne by those agencies and commuters, the benefits would largely accrue to property owners nearby who would see their land values skyrocket. Getting all those property owners to chip in wouldn’t be easy. Many would be tempted to free-ride: skip paying their fare share, hoping that others would make up the gap. The transaction costs to get everyone on the same page— the time lost, lawyers fees, and consultants bills—are huge for any single entity to take on, especially compared to the diffuse benefits they would get if the project succeeded.

For individual projects like this, mechanisms exist to force the beneficiary property owners hands, like creating a tax-increment financing district or a business improvement district, which only require a majority of the property owners in a designated area to sign off on paying an extra fees or redirecting property taxes to support a mutually beneficial investment. These programs are designed specifically to address the huge transaction costs, but even they require a ton of upfront work. Moreover, they’re really only designed to cover minor expenses, like street-cleaning and extra lighting, not massive investments. Still, larger projects draw attention, which brings the right stakeholders to the table.

But that’s not the case with most city streets and most street projects, which can require similar levels of coordination without the noticeable payoffs. We notice big shiny things, and huge ugly potholes, but when the water department works with streets to replace a parking spot with a curb bump out and a stormwater tree trench, it’s lucky to be covered by a hyper local blog. It rarely captures the public’s imagination.

Projects like that are why the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities exists. It’s why the DVRPC brings representatives from seven counties, four cities and two state governments together, along with officials from SEPTA, DRPA, PennDOT and federal transportation authorities. And it’s why staffers from city agencies, SEPTA and the DVRPC convene as the Transit First Committee: to overcome institutional barriers to cooperation. To lower transaction costs.

In Philly today, we’re lucky that these agencies exist and everyone can get on the same page as often as they do. In the early 2000s, SEPTA and the city couldn’t stand each other. When SEPTA tried to consolidate stops along its 52 Bus and the 15 Trolley, it was met with “significant community pushback” according to a 2013 report authored by the Transit First Committee. “Without support from the City, SEPTA’s efforts were minimized to the point of ineffectiveness and the program ultimately became inactive.”

The Transit First Committee was first convened in 1989 via an executive order from Mayor Wilson Goode Sr. It stopped meeting during John Street’s tenure as mayor as the relationship between the city and SEPTA grew toxic. The Committee was revived after Michael Nutter took office and has met regularly every since. According to Greg Krykewycz, the DVRPC’s transit, bicycle and pedestrian planning manager, the Transit First Committee has helped interagency relations tremendously.

Come January, Philadelphia will have a new mayor, a new set of department chiefs and deputy mayors – a new way of doing things around here. It should give us all pause: the recent era of cooperation could come crashing down with just a clash of personalities.

But that’s just a risk appurtenant to splitting a large, generalist department into specialized, focused agencies.

*CORRECTION: In writing this, Jim mistakenly left out the DRPA from the list of agencies with responsibility over streets. There are thus 9, plus private entiries, with responsibility over city streets.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.