When moles go bad: Penn scientists identify commonly lost protein that protects against melanoma

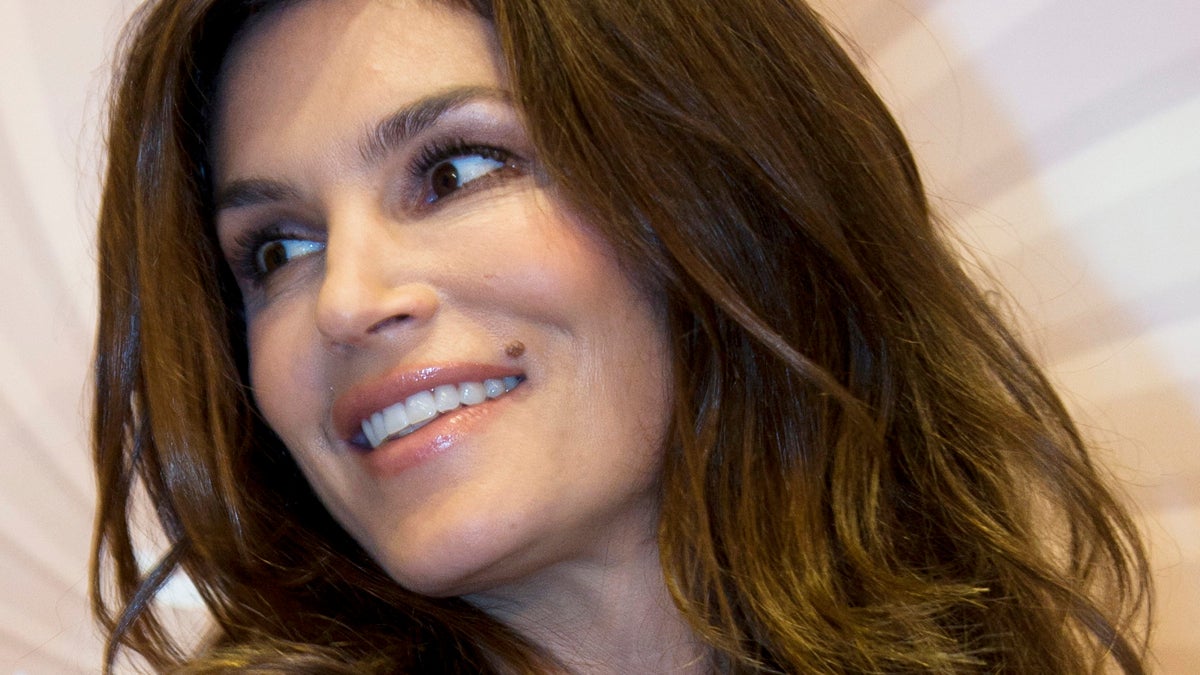

Supermodel Cindy Crawford and her trademark mole. Penn researchers have gained insight into why moles stop growing and why some turn cancerous. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)

The vast majority of moles — whether embraced as a beauty mark or disdained as a blemish — are harmless. But on occasion, they can be deadly.

New findings from the University of Pennsylvania help explain why only some moles make the switch to melanoma and might offer a better way to distinguish the cancerous growths.

Scientists have known for a while why most moles start growing: a bit of sun damage causes a gene called BRAF to mutate.

“That’s like a gas pedal that makes the cells divide,” said Penn dermatologist Todd Ridky, a senior author of the new study published in the journal Cancer Discovery.

Less clear was why nearly all moles stop growing after a year or two, once they’ve reached about the size of a pencil eraser.

Using a new human-based model for studying melanoma, Ridky’s team found that is often because a protein called p15 steps in. The real problem begins if p15 is lost and its brake on growth is removed.

“Every single benign mole we looked at had p15,” said Ridky. “Whereas p15 protein in melanomas was sometimes there, but very often absent.”

A test for evaluating moles for cancer in this way is not yet available in clinics, he said, but could be ready within a few years.

A quarter to a third of all melanomas begin in a pre-existing benign mole.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.