When Camden was Silicon Valley — and glimpses of a med-tech turnaround

Listen

An old, yet functioning, Victrola on display at the RCA Heritage Program Museum at Rowan University. (Zack Seward/WHYY)

Camden, New Jersey used to be a tech hot spot. Now, the troubled city is showing signs of life around health care.

Few people see Camden, N.J., as a hotbed of consumer tech innovation. But in its day, that’s what it was.

RCA-Victor birthed many of the 20th century’s most cherished devices. But that was then. Now, there’s hope that a new era of invention, with a medical focus, can lift up this struggling city.

And with a recent influx of investment by a handful of institutional anchors, it might even pan out.

Tech firsts

Joe Pane and Jim Hemschoot are company men: 61 years of service between them to good old RCA, which put Camden on the map with a heap of national firsts.

The first radio show broadcast in 1920.

The first consumer television set in 1939.

Sonar.

Walkie-talkies.

More.

Pane, Hemschoot and I are looking at a 15-foot timeline stretched across a wall of the RCA Heritage Program Museum. Pane and Hemschoot run the place. It’s a room-and-a-half housed in Rowan University’s main library, and it’s packed with mementos of RCA’s technological preeminence.

Hemschoot fires up an iconic RCA relic built in Camden by the Victor Talking Machine Company, before RCA was even RCA.

“This Victrola, with the Caruso record, is essentially a 105-, 106-year time machine,” Hemschoot says.

But the legacy of RCA is more than just Caruso.

“RCA created the middle class in South Jersey,” says Pane.

Hemschoot agrees, likening Camden then to Silicon Valley now. “It brought in the secretaries and it brought in the cabinetmakers and the machinists and the factory workers,” Hemschoot says. “People would come in to New Jersey because there were so many jobs here.”

Engineers were stars.

“We worked hard, but we played hard, too,” Hemschoot adds.

Phonographic roots

It all started in 1901 with that famous dog, Nipper, staring into a phonograph. The Victor Talking Machine Company was in Camden first.

RCA came along in 1919 at the behest of the U.S. government. America needed the radio technology its European counterparts had flaunted during World War I.

GE was tasked with creating RCA, and the military gave the new company rights to the nation’s radio waves.

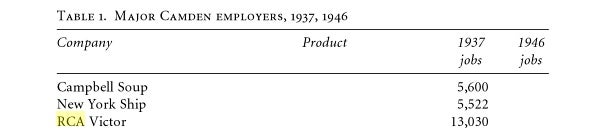

By 1937, RCA was Camden’s top employer, with over 13,000 workers, about a tenth of the city’s entire population at the time.

(*Source.)

Hemschoot says things picked up after World War II, with RCA becoming a leading commercial partner of a then-nascent security state.

“National security became more important, the Cold War,” says Pane.

You probably know RCA as an entertainment company, but plenty of kibble was flowing into Nipper’s bowl by way of contracts from the Department of Defense and NASA.

“The International Space Station,” Hemschoot says. “We still do the communications and tracking system. All of the video and all of the audio and all of the tracking that you see from the International Space Station came from Camden.”

But as RCA’s fortunes rose, things for its home city began to crumble.

The good times peaked in the mid-50s. Then the familiar tale of white flight and political corruption set in. The 70s were really bad. And in the 80s, crack hit.

RCA was bought by GE in 1986 and basically sold for parts.

“We got lapped in the computer area,” Hemschoot says.

The timeline at Rowan’s RCA museum ends with the 20th century.

“We kind of lost interest in what’s happening after that,” says Hemschott.

But much of the engineering spirit of RCA still remains in Camden. Many of its innovations and firsts live on under a different name.

Camden’s defense contractor

“We are in the L-3 Communications Systems-East operations facility,” says Dave Micha, the president of the local division of L-3. “This is where everything we design gets manufactured.”

L-3 Communications Systems is located right under the old RCA tower in downtown Camden, which was converted into lofts about a decade ago. This is a modern-day factory floor. No Victrolas here. Misters in the rafters keep precision electronics appropriately humid.

“This is state of the art manufacturing, absolutely,” Micha says.

Over 700 people work at L-3 — they’re hiring, actually — and about half are engineers. L-3 is basically continuing the work of the top-secret wing of the defunct RCA. Its bread-and-butter is secure communications.

“About 75 percent of the work we do is very classified, so we can’t get into a lot of details of that,” Micha says. “Suffice it to say, the things we do here provide equipment for the men and women in the armed services who are protecting this country.”

Micha says 100 percent of his division’s work is for the Department of Defense, the intelligence agencies or foreign militaries.

The day before we met, he was in Maryland meeting with the NSA, which has worked with RCA since 1960.

The stuff L-3 can talk about is secure phone terminals used by nearly all Washington officials to talk classified information; battlefield sensors1 used in Iraq and Afghanistan that can detect approaching enemies; and the communications systems used on warships.

“The stuff we do is many years ahead of what you would find, in many cases, in commercial industry,” Micha says.

The company is not all that well known outside of the military contractor community, Micha admits. A lot of the work can’t be advertised. But he says the hope is that keeping an engineering spirit alive in the poorest city in the nation will help lead to better days.

“I’d like to make it the next Silicon Valley,” Micha says. “That’s a stretch goal.”

Building momentum

Micha’s a company man, too — he started work at RCA in 1984 and climbed the ranks to the top of L-3. He’s seen things change in Camden, now a city of just 77,000.

He and others I spoke with say they’re more optimistic than they’ve ever been about a Camden turnaround — largely because of another high-tech force building up strength.

“We have an emerging scientific community here in Camden,” says Steve Trzeciak, a clinical researcher at Cooper University Health Care. “It’s really exciting to watch.”

That growing source of momentum, you guessed it, is the health-care sector.

“I think that our emerging scientific community represents opportunity,” Trzeciak says. “Over the next five years, 10 years, I think others will see that opportunity and gravitate here to test new innovations.”

The biggest proof of a new gravitational pull may be the new partnership between Cooper and the University of Texas’s MD Anderson Cancer Center.

MD Anderson has been America’s top ranked cancer care for several years now. Getting it to open an east coast base of operations in Camden was a major victory.

(It’s worth mentioning that the chairman of the Cooper board is South Jersey political boss George Norcross, whose influence has been credited with helping speed recent development in Camden.)

The new MD Anderson Cancer Center at Cooper opened just a few months ago. The sleek building accounts for a good chunk of a mini construction boom in Camden.

According to new figures from a forthcoming report by the Cooper’s Ferry Development Association, there has been $455 million in construction activity in Camden since 2011 alone.

Cooper’s Ferry, the city’s economic development outfit, says the vast majority of that spending has come from Camden’s big nonprofits — the “eds and meds” sector flexing its muscle.

Over 42 percent of the jobs in downtown Camden are in health care, according to the forthcoming Cooper’s Ferry report. That’s how big of a player the sector is becoming.

But will it work?

Camden is seeing positive movement, local observers say. But its problems run deep.

A reorganized police force has seen early gains in fighting the city’s staggering crime rate.

The institutional pillars of Camden’s “scientific community” — from Cooper to Rutgers-Camden to Rowan (whose new status as a research university is an economic boon) to the Coriell Institute — are planting major stakes.

But the green shoots of private development sprouting up around those pillars aren’t really there yet.

Observers are cautiously optimistic, however. Even if things are heading in the right direction, it will take time and a bit of luck for science to again put Camden on the map.

____________

1 A tangential footnote. The name of this battlefield sensor system under RCA — “REMBASS” — got its 15 minutes of fame via Bruce Springsteen. He wore a red hat with the REMBASS logo in the music video for “Glory Days.” It’s also allegedly the same hat featured on this famous album cover. L-3’s Dave Micha has the tale of how the Boss got the hat. It’s in the audio player below.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.