Welcome to the Philly school principal version of speed dating

Listen

Phillip DeLuca, principal at Samuel Gompers school, is shown talking to a potential nonprofit partner at the School District of Philadelphia's annual Partnership Fair. (Avi Wolfman-Arent)

Each year dozens of nonprofits and public school principals gather for a ritual that looks kind of like a well-lit version of speed dating. There are long rows of tables, roving herds of unmatched hopefuls, and even some awkward small talk.

Except, instead of talking about settling down and having kids, the conversations are about helping kids.

Welcome to the School District of Philadelphia’s annual Partnership Fair, a chance for principals and nonprofits to feel each other out and see if they can work together.

This year’s version featured about 50 organizations, each with its own pitch and literature. A few even offered bowls of candy to draw interest.

They’re all hoping to catch the eye of building administrators, each of whom is looking for something different.

Marlita Thorn, assistant principal at John B. Kelly School in Germantown, took special interest in an organization offering grief counseling because, she says, so many students at her school lose a friend or relative to violence.

“Our community is losing so many people so quickly, the children, they don’t know how to grieve,” said Thorn. “I would love to have someone come into the school and talk to the children and show them how to channel those emotions.”

Laurena Tolson, principal at West Philadelphia’s Add B. Anderson School, zeroed in on the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia, which offers Model United Nations and other similar activities. Tolson wants to close what she calls the “exposure gap.” More than eight in 10 Anderson students are classified economically disadvantaged, which means they can’t always pay to sign up for extracurricular activities like kids in wealthier neighborhoods do.

“We spend a lot of time thinking about the achievement gap and not necessarily always thinking about the resources and opportunities to fill that exposure gap so that our students are competitive within the city of Philadelphia and across our world,” Tolson said.

There are a lot of nonprofits and community groups working in Philly’s public schools: 1,081, to be exact. That figure comes from a school support census prepared by the district’s Office of Research and Evaluation and the Office of Strategic Partnerships, whose work provides fascinating insight into the easily overlooked world of nonprofit partners.

Most partners are small. But considered as whole, these organizations form a critical web of support. They are the caulk that fills so many gaps in Philadelphia’s cash-strapped schools.

“This is serious business,” said Thorn. “And it feels good that the community and outreach programs come to us and let us know, ‘Hey, we got your back,’ when it comes to these things if you guys aren’t able to provide them for yourselves.”

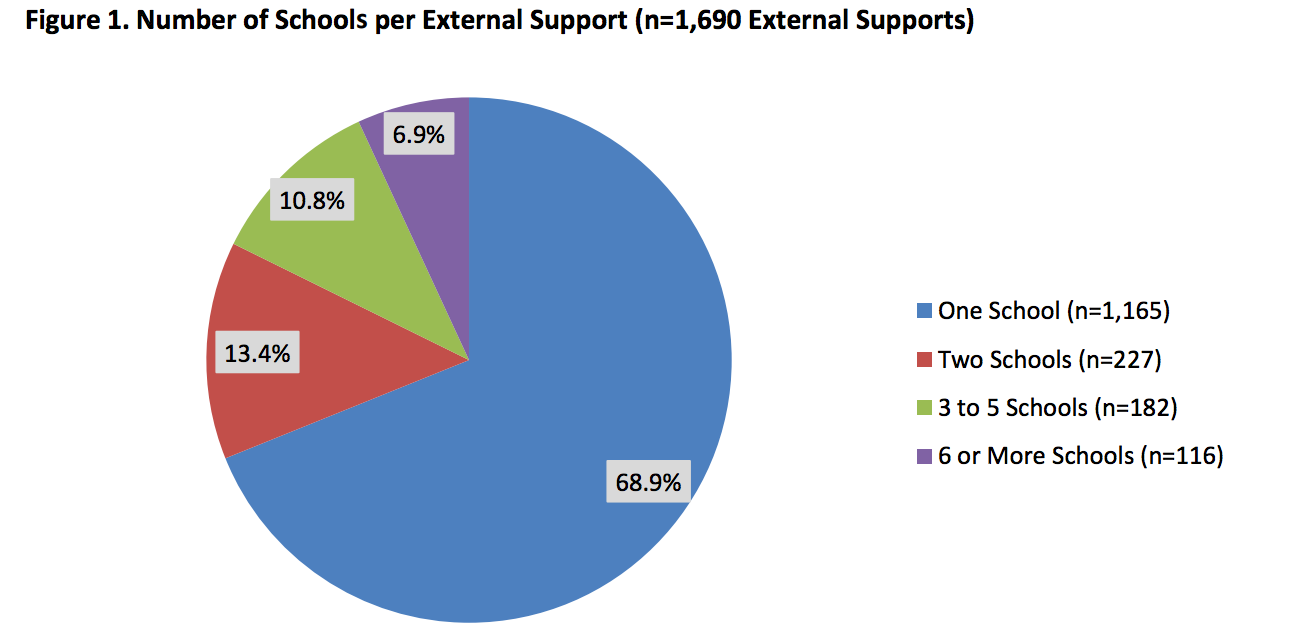

The average Philly school has 18.2 “programs and/or support relationships,” according to district data. Nearly 70 percent of those external supports exist in a single school, as opposed to several.

(Source: School District of Philadelphia)

(Source: School District of Philadelphia)

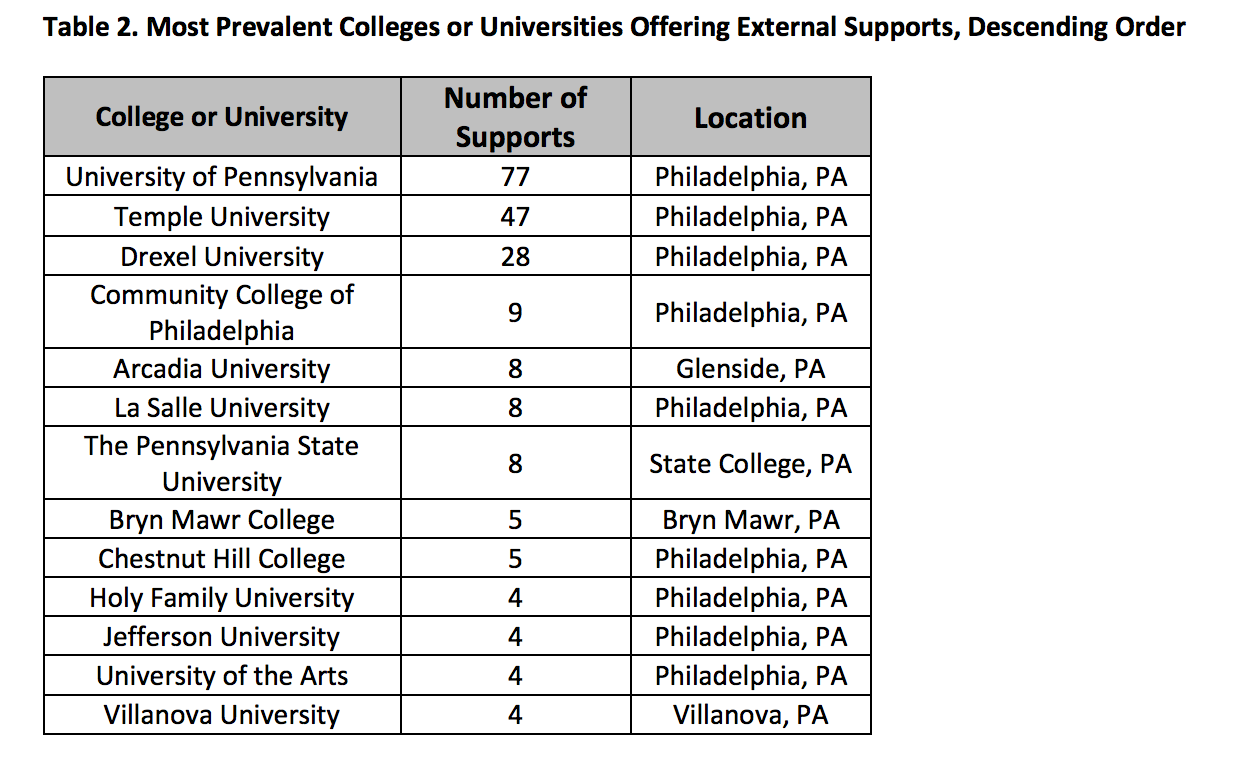

Some of those supports come from hyperlocal groups like neighborhood churches. To the extent there are big players in the school-partnership space, local universities might fit the bill.

(Source: School District of Philadelphia)

(Source: School District of Philadelphia)

Still, school leaders report plenty of unmet needs. More than half of schools say they could use more mentoring and mental health services.

There’s a natural limit, though, to what this patchwork of non-profit partners can provide. Many principals told the district they didn’t have the capacity to juggle more external relationships — even if they could use more help.

There is a potential solution to this structural flaw: school-level coordinators whose primary job is to manage and oversee outside relationships. Only about a quarter of Philly schools report having one, but the push is on to create more coordinator positions.

Through its community schools initiative, the Mayor’s Office of Education plans to create 25 community schools, each with their own community schools coordinator.

At other schools, like Alexander Adaire in Fishtown, the AmeriCorps/Vista program pays for community partnership coordinators. In that role, Adaire parent Sasha Best oversees more than 80 external relationships.

“It’s the best job in the world,” she said. “I’d do it for free.”

Sometimes in Philly schools there are so many people who want to help, you need more helpers.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.