Vision Zero Action Plan: A Modest Proposal

On Tuesday the City of Philadelphia released a draft of its Vision Zero Action Plan, a three-year roadmap for the first leg of a long march towards zero traffic fatalities.

Everyone PlanPhilly spoke with agreed: Reducing the number of deaths from car crashes to zero is the kind of goal anyone can get behind.

“The idea to protect the public and reduce the number of traffic fatalities and traffic accidents is obviously a laudable goal,” began Paul Hetznecker, a civil rights and criminal defense attorney in Philadelphia.

“While I think the effort is laudable,” Jake Liefer, a co-chair of the urbanist PAC 5th Square, started to say.

“Anything that purports to help safety for motorists, bicyclists, pedestrians… I certainly support,” prefaced Councilman Bill Greenlee.

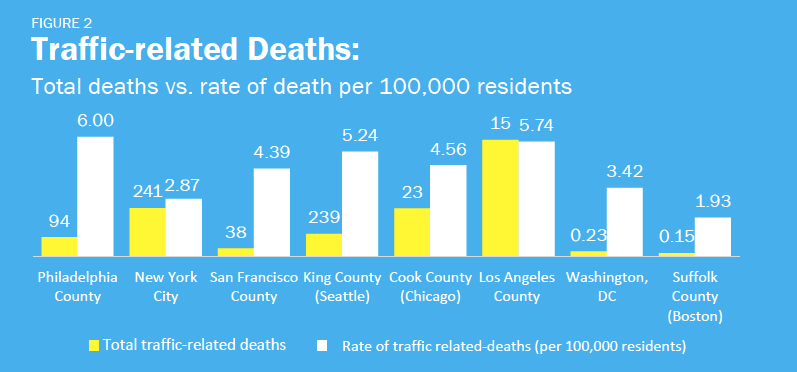

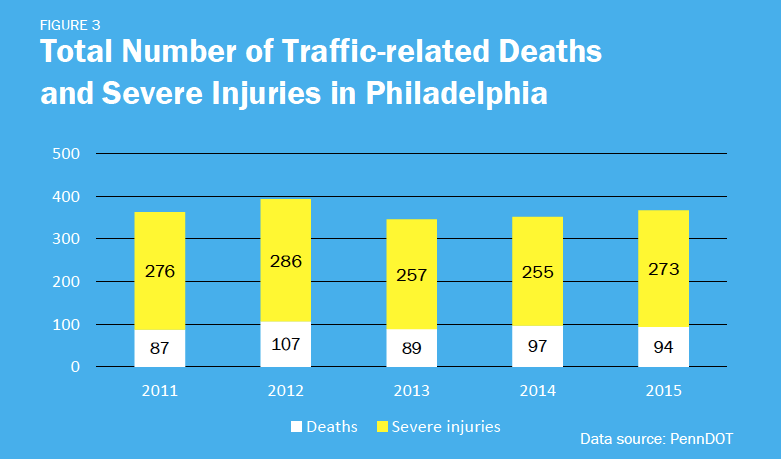

But just how to get from here (76 traffic fatalities in 2016 and 94 in 2015) to there (zero traffic deaths by 2030) is where the safety initiative’s rubber meets the political road.

While everyone PlanPhilly spoke to started out by cheering Vision Zero’s goals, they went on to express concerns about the implementation.

Hetznecker took issue with the Action Plan’s call for increased traffic enforcement. “That particular model, if imposed in communities, poor communities, African American, Latino communities, should draw very, very careful scrutiny from all of us…. Traffic stops have been used as pretexts for unconstitutional searches and seizures.”

Liefer immediately worried that the Action Plan wasn’t ambitious enough. “I’d like to see more measurable and defined goals for implementation of a citywide plan, for enforcement and installation of the necessary infrastructure.”

Councilman Greenlee, who sponsored the 2012 legislation that gave City Council authority over changes to road designs, said he was concerned it might be too ambitious.

“I’ll have to see more specifics,” Greenlee said, particularly about an action item to work with Council to authorize the city’s chief traffic engineer to “implement traffic calming and traffic safety improvements through changes to road markings, signage, and lane configuration that can be justified based on a formal review of crash data and relevant engineering characteristics” of the site in question.

“I don’t think most council members will say they want to leave it up to chief traffic engineer to make all the decisions,” added Greenlee. “I think it would have to be in some kind of conjunction with Council.”

Officials in the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems (OTIS) have high hopes based on Vision Zero’s marketability. In an interview with PlanPhilly earlier this year, OTIS Deputy Managing Director Mike Carroll said Vision Zero would empower the office to overcome the inertia that often dooms safety improvement projects. His chief of staff Michael Zaccagni described Vision Zero’s impact this way: “It’s obviously something that nobody can argue against. I mean, what we’re trying to do is save lives.”

The city’s director of complete streets, Kelley Yemen oversaw the task force that put together this draft action plan. When asked about the early criticism about some of the plan’s specifics, Yemen said she welcomed the dialogue. “We will have the initial conversations rather than getting wrapped up in the specifics of this or that project: It’s let’s build the general buy-in of we can all support safety and we can all support safe streets for our kids.”

The announcement of the draft Vision Zero Action Plan fulfills the last of Mayor Jim Kenney’s campaign promises on traffic safety. During his mayoral campaign, Kenney pledged to adopt a Vision Zero goal, create a taskforce and publish a plan. Once the Action Plan is finalized—Yemen gave September as the due date—all of that will have been accomplished. Of course, it’ll be the implementation that ultimately matters.

Still, the draft’s publication won praise from the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, the city’s de facto traffic safety advocacy group and leaders in the Vision Zero Alliance. “We are generally encouraged by it for a few reasons,” said spokesman Randy LoBasso. “The first of which is that it exists.”

“There has been a lot of talk over the years about doing things [and now] we have this draft plan, which is generally just encouraging. I’ve been in Philadelphia for almost 15 years and I’m used to things just sort of going away.”

That’s not hyperbole. In recent years, plans for redesigning Washington Avenue, Market Street, John F. Kennedy Boulevard, and 22nd Street all withered on the vine.

WHERE THE RUBBER MEETS THE ROAD

The draft action plan runs long on ideas but short on details. That’s by design, said Yemen. “We want to really drive people to look at the plan, give us comments, engage with us on what else they want to see in the plan before we finalize it.”

Yemen said the administration wanted to be “tactical,” focusing on policy interventions the office could realistically implement over the next three years.

“We didn’t want this to be a pie in the sky plan,” she said. “Hopefully, we can really make changes by using what we have in a different way.”

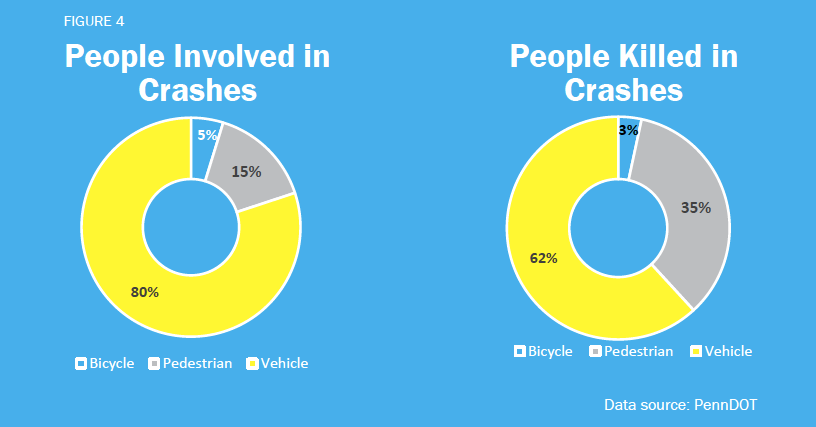

While the draft didn’t identify where the interventions would go, the final plan will, said Yemen. “It will follow where we are having the crashes.” Yemen added that locations with “life altering crashes” fatalities would get attention above less-serious collisions. “We’re not going to chase fender benders around the city.”

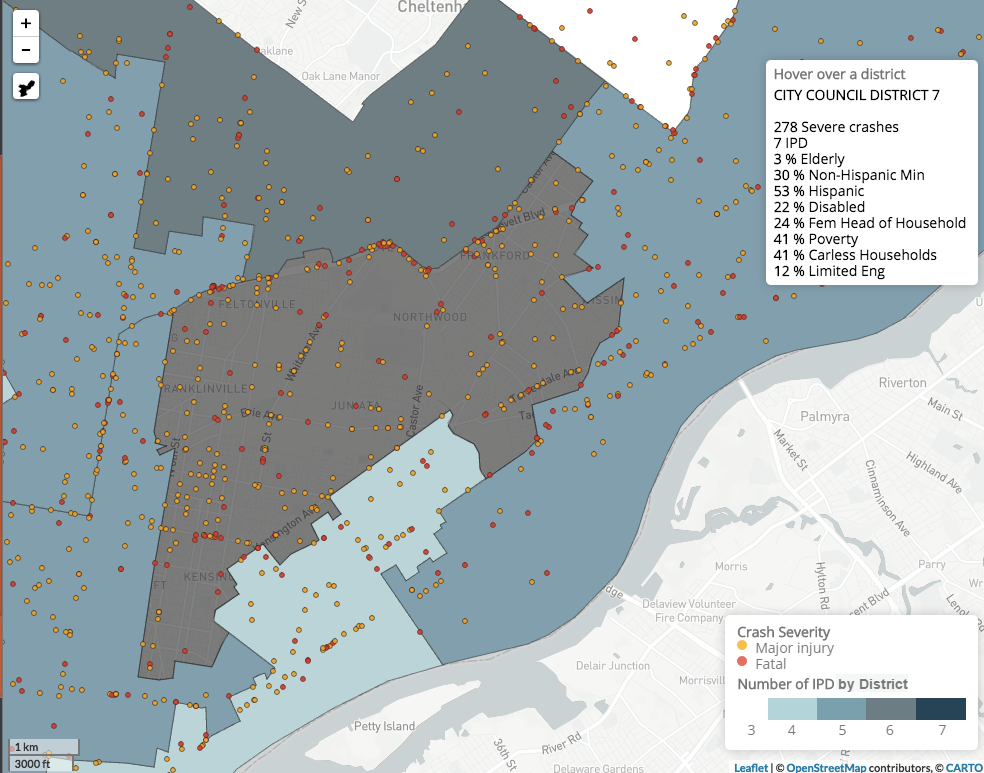

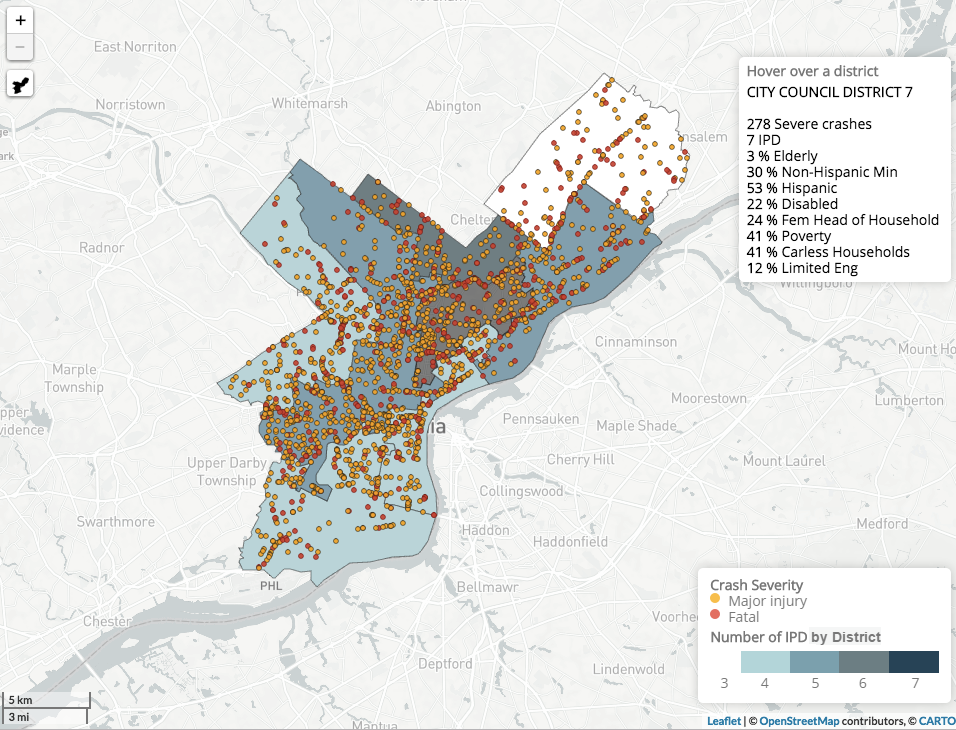

There is no shortage of maps that already show where these kinds of crashes occur. Over the summer, local software company Azavea’s Summer of Maps program worked with the Bicycle Coalition to build a map of traffic crashes between 2010 and 2015 that resulted in serious injury or death. The Coalition also maintains a map of each traffic fatality in the city. As these maps (and others) show, the streets in some of the city’s most impoverished neighborhoods see some of the worst traffic violence. The 7th Councilmanic district, represented by Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, had the most severe crashes from 2010-2015. It’s also the city’s poorest district.

If OTIS follows the data, it’ll be neighborhoods like Kensington, Fairhill, Logan, and Cobbs Creek that will receive new crosswalks, brighter streetlights, and protected bike lanes—the kinds of design interventions recommended to support Vision Zero.

Those are the same kind of neighborhoods that has Hetznecker nervous about how Philadelphia implements Vision Zero. The plan calls for streetscape improvements and public education, but it also calls for stepped-up traffic enforcement. While Hetznecker supports the first two, the latter feature has him concerned: more contact with cops comes with higher risks for communities of color.

“I think that community outreach becomes critical to this,” said Hetznecker. “Raising the specter of punishment or punitive measures to deter reckless driving is a serious mistake. That would be the one component of this Vision Zero program that should be jettisoned.”

Outreach and investment will come first, said Yemen. The plan doesn’t call for increased enforcement until 2019, “to give us time to hopefully ramp up on education and engineering solutions before we would ever engage in enforcement.”

Moreover, the police will focus on egregious behavior, not just the run-of-the-mill bad driving we’re all guilty of from time to time. “It’s really enforcing the outliers rather than… poor driving behavior [or] poor walking behavior,” said Yemen. “It’s setting people up for success rather than coming down with harsh punishment where investments have not been previously made.”

Whether the poorer neighborhoods will be targeted for the streetscape improvements in the final plan remains to be seen. In addition to in-person community outreach over this summer, OTIS has launched a website to begin soliciting resident feedback. But according to Pew research, lower income households and minorities still lag behind in Internet access.

Moreover, Center City and University City both have very high crash rates, by-products of the sheer volume of people and cars there every day. One can reasonably argue that pedestrian and bicycle improvements there will help the most people.

Hetznecker worried that Vision Zero might simply accelerate a broader trend in the city: the affluent downtown gets showered in investment green while the poorer neighborhoods get smothered in police blue.

Currently, the city has plans for protected bike lanes along Pine and Spruce Streets in Center City, and another along Chestnut Street in University City—two well-off city neighborhoods. It’s first protected bike lane was built on Ryan Avenue in middle-class Mayfair. The first two schools to see concentrated safety improvements under the city’s Safe Routes to School program were located in rapidly gentrifying Point Breeze and East Passyunk neighborhoods, even though schools in poorer North and West Philly neighborhoods also met the criteria of 15 child pedestrian crashes within a few block radius of the school over a 2010-2014 time period.

Not all of the city’s investments are happening in wealthier neighborhoods. North American Street in Kensington is also being redesigned (although the blocks surrounding the southern half of the road have begun to gentrify). Roosevelt Boulevard is also in the middle of a multiyear planning process aimed at making the wide thoroughfare through most of Northeast Philadelphia safer.

According to Hetznecker, the worst thing that could happen would be if the City “put the resources in Center City for all the lighting, and crosswalks and speed bumps on Walnut Street or on Broad and you don’t do anything but enforcement in the neighborhoods.”

When he said that, Hetznecker didn’t yet know that the city’s most recently announced new traffic improvement for Center City are raised crosswalks on Broad Street at Walnut and Chestnut streets.

Those two crosswalks will satisfy one of items on the draft plan’s list of near-term engineering projects: “Install two raised intersections.” Other items on the list, like installing new LED lights and pedestrian countdown timers, have been ongoing.

What Yemen described as “realistic” and “tactical”, 5th Square’s Liefer called “frustrating.”

“We’re looking at two raised pedestrian intersections in two years,” said Liefer. “That’s one raised intersection per year. With over 2,000 miles of roadway that the City of Philadelphia maintains, at one intersection per year, that seems like we’re pretty far off from getting to [the] goal [of zero vehicular deaths by 2030].”

On the page, the Vision Zero Action Plan’s lists of engineered improvements, educational initiatives, and enforcement goals read as scattershot and unfocused— would the goal of building “two curbless streets” be satisfied if one was a tiny alley and another the work of private developers? Yemen said the final plan would have more specifics, noting again that crash data would drive location choices.

Still, Liefer’s group wants to see the city take a more ambitious tact to street safety. To 5th Square, the problems and solutions are clear at this point. It’s time to stop talking safety and to start walking safely.

“We’ve researched the problem multiple times over,” said Liefer. “We need to get to implementation at this point.”

Liefer sees the problem as one of political will, namely allowing the loudest neighborhood complaints about specific safety proposals trump systemic safety improvements, pointing to Washington Avenue’s stalled overhaul.

The draft Action Plan seems to address that issue with its first policy proposal: “Work with City Council to draft legislation authorizing the Chief Traffic Engineer to implement traffic calming and traffic safety improvements through changes to road markings, signage, and lane configuration that can be justified based on a formal review of crash data and relevant engineering characteristics of subject intersections and roadway segment.”

Yemen said the idea is to provide the chief traffic engineer the “flexibility to rapidly respond to high crash locations,” without needing Council’s blessing for each individual project.

In 2012, Councilman Bill Greenlee introduced the bill that mandated Council’s approval for any road redesign, such as when a bike lane could replace a travel or parking lane. Since then, there hasn’t been a single new bike lane built that replaced an automobile travel lane or a full parking lane.

When asked specifically about action plan’s proposal to preapprove street redesigns when certain crash-related criteria were met, Councilman-at-large Bill Greenlee expressed skepticism. “I think Council would probably want to be more directly involved in specific cases than just saying: ‘Here’s the policy, you do what you want to.’”

Yemen said the final plan in September would be followed up with annual progress reports and updates.

The Bicycle Coalition applauded the move. “The city has provided itself with accountability,” said LoBasso. “They have a document, a website, and that is all very positive.”

As with all government initiatives, questions about funding and organizational capacity may ultimately limit ambitions. Yemen said OTIS and Streets would keep costs down by designing many of the street interventions in-house. The complete streets director also stressed that much of this work was already ongoing and budgeted for. “A lot of this is how to focus [those funds] to make the biggest impact toward improving safety.”

In that regard, the plan amounts to a modest proposal: To depoliticize street safety projects, let city engineers advance best practices in complete streets, and allow severe crash data dictate when and where roads get reconfigured. Whether the Mayor will be willing to expend political capital on this initiative, however, remains to be seen.

Yemen couched Vision Zero as part-and-parcel to the Mayor’s broader focus on Philadelphia’s children: Kids need safe walks to the city’s expanded pre-kindergarten offerings and newly rebuilt parks and rec centers. “How are we building a city that supports our children,” Yemen asked rhetorically. “We can all support safe streets for our kids.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.