Villanova engineers create device to monitor athletic performance, head impacts

Listen

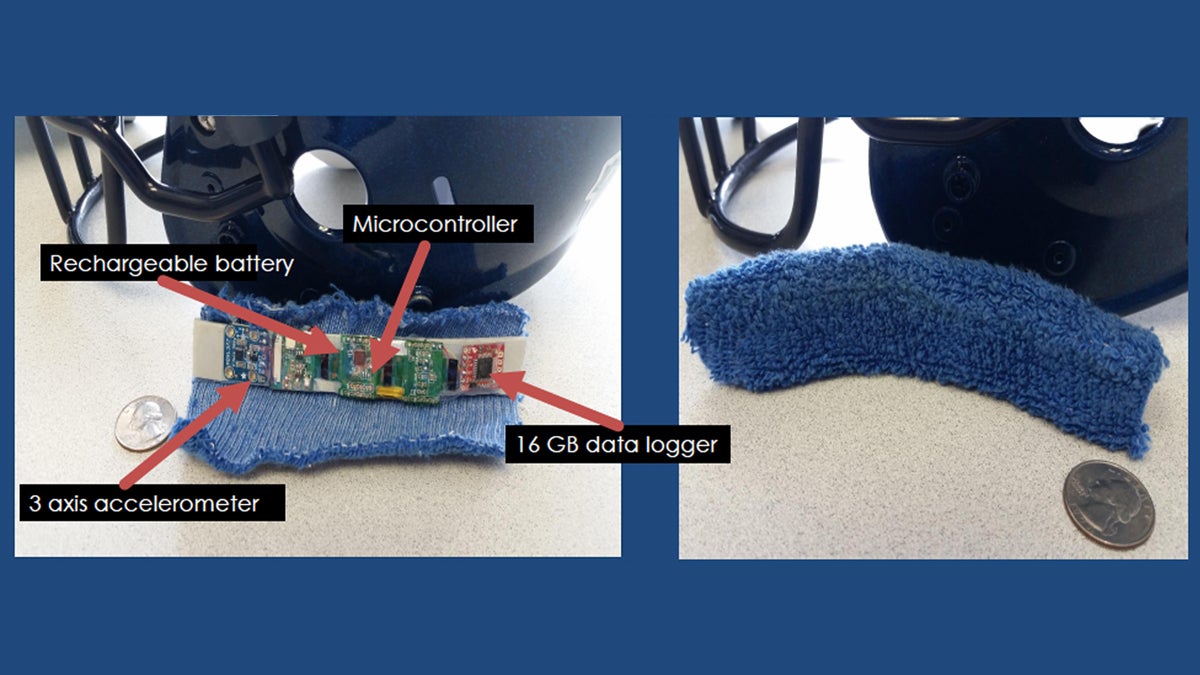

Researchers and engineering students at Villanova University have come up with a wearable device that monitors everything from steps taken to the severity of hits to the head (Images courtesy of Villanova)

Researchers at Villanova University are jumping on the personal fitness monitoring craze to get more data on head injuries in sports.

Assistant professor Ed Dougherty and his engineering students have come up with a wearable device that monitors everything from steps taken to the severity of hits to the head.

“It will measure head impacts and collect that data over long periods of time, but it can also be used as a general activity monitor, which could be used to be measured the performance of the athletes over time, or even in a particular game,” said Dougherty. “That would make it attractive for someone to wear on a daily basis.”

Another difference between this and other head impact monitors? This insert works with different kinds of sports helmets – or no helmet at all.

“We envision that you could be wearing it in a football helmet in the morning, and then in the afternoon when you’re out playing soccer with just a headband. It almost looks like a headband that you might wear for tennis,” says Dougherty.

The device contains an accelerometer to measure impact, as well as a radio transmitter to broadcast information to the sidelines, and can store up to 16 gigabytes of information about sports performance.

“We’re really hoping people use this so we can collect data on brain impact, but we’re attempting to do it by adding all of these additional features,” he said.

Those added features and functions, said Dougherty, could lead to more comprehensive head impact data.

“Wouldn’t it be cool if a kid could wear this from 10 years old to 70 years old?”

Race between science and technology

For more than 10 years, researchers have been experimenting with safety measures for sports-related traumatic brain injuries or TBIs – from better helmets to impact monitors like the Villanova prototype. Barriers to adoption include cost and size.

Another hurdle? “We don’t have objective markers for concussions,” said Dr. Kristy Arbogast, the co-scientific director of the Center for Injury Research and Prevention at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There’s no blood test, there’s no brain scan.”

Different people experience the same impact differently, depending on factors including age and genetics.

“I think what we have to be careful about is having the technology and the policy get ahead of the science,” said Arbogast. And because impact monitors all work differently, and have a margin of error, there is no scientific way to evaluate the data they provide, she said.

“Fundamentally, we’re headed in the right direction, we just don’t know how to interpret these values yet,” Arbogast said.

“We want a quick fix, but it’s not,” said Dr. Rosemarie Moser, director of the Sports Concussion Center of New Jersey. She has, however, seen success when there is an effective way to use impact monitors to spot a head impact early. “[As a coach], you can’t watch every impact on the field,” she said.

Transmitters like the one in the Villanova device can signal a coach or trainer that a player might need to be evaluated for a concussion. But, she stressed, “We need to have the health care and the staff.”

She and Arbogast say low-tech interventions such as baseline testing and appropriately trained staff are at least as important as an impact monitoring tool – and recommend all schools and sports leagues have an action plan for concussion prevention and detection.

Each year, emergency rooms in the United States treat over 170,000 sports-related traumatic brain injuries, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dougherty is working with the Villanova athletics programs to pilot the monitors with school’s sports teams early next year.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.