U.S.-China trade talks center on rivalry over technology

Chinese and U.S. officials met face-to-face Thursday in an attempt to resolve a dispute that has taken the world's two largest economies to the brink of a trade war.

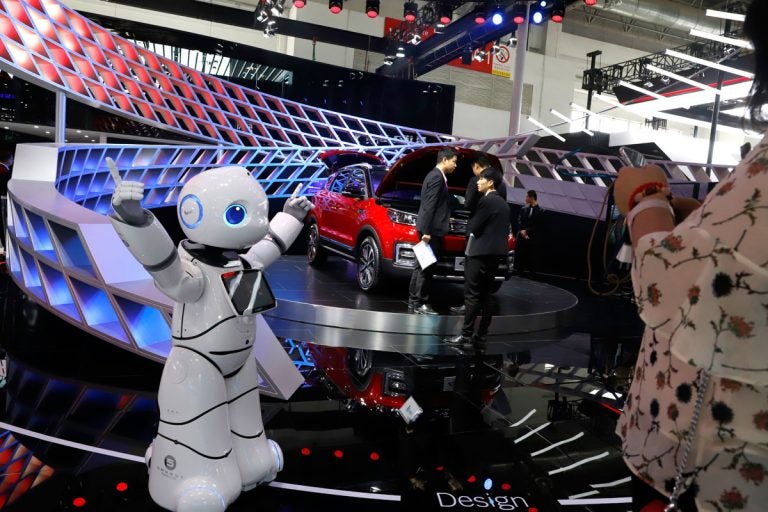

In this April 26, 2018, photo, a robot entertains visitors at the booth of a Chinese automaker during the China Auto 2018 show in Beijing, China. Under President Xi Jinping, a program known as "Made in China 2025" aims to make China a tech superpower by advancing development of industries that in addition to semiconductors includes artificial intelligence, pharmaceuticals and electric vehicles. (Ng Han Guan/AP Photo)

Chinese and U.S. officials met face-to-face Thursday in an attempt to resolve a dispute over technology that has taken the world’s two largest economies the closest they’ve ever come to a trade war.

A high-powered U.S. delegation arrived in Beijing for talks with Chinese officials aimed at defusing the tensions, though analysts say they appear unlikely to yield a breakthrough given the two sides’ intensifying rivalry in strategic technologies, where China lags behind the U.S.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is leading the group, which includes Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer. Liu He, President Xi Jinping’s top economic adviser, headed the Chinese side in the talks, which are expected to end Friday.

The dispute has deepened as China has stepped up efforts to overtake western industry leaders in advanced technologies, especially for semiconductors, the silicon brains required to run smartphones, connected cars, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence.

Under Xi, a program known as “Made in China 2025” aims to make China a tech superpower by advancing development of industries that in addition to semiconductors includes artificial intelligence, pharmaceuticals, and electric vehicles. The plan mostly involves subsidizing Chinese firms. But it also requires foreign companies to provide key details about their technologies to Chinese partners.

U.S. President Donald Trump is seeking to cut the chronic U.S. trade deficit by $100 billion and gain concessions over the policies that foreign companies say force them to share technology in order to gain market access.

His administration has threatened to impose new tariffs on roughly $150 billion in Chinese goods. That prompted China to announce its own tariffs on U.S. goods, and Beijing also looks unlikely to cede any ground on its strategic blueprint for technology.

“The Made in China 2025 industrial policy concerns China’s long-term development plan, so the overall direction won’t change at all,” said Yu Miaojie, professor at Peking University’s National School of Development. Yu says China would rather cut the trade deficit by importing high-tech products from the U.S. that are currently tightly restricted.

The state-run Global Times newspaper said Thursday in a commentary that it’s “our sovereign right to develop high-tech industry and it is connected to the quality of rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. It will not be abandoned due to external pressure.”

Washington’s recent decision to ban Chinese telecom gear maker ZTE from importing U.S. components in a sanctions-related case drove home to Beijing its costly vulnerability to foreign sources for advanced microchips.

The “Made in China 2025” plan calls for domestic producers to supply 70 percent of the country’s chip demand.

The Trump administration’s efforts may actually spur China to ramp up efforts to develop its domestic industry as it strives to fulfill Xi’s vision, said Jian-Hong Lin, an analyst at research firm TrendForce.

China now consumes nearly 60 percent of the world’s semiconductors but supplies only about 16 percent, according to PWC. The country spends more than $200 billion a year on foreign-made semiconductors, which in 2015 surpassed crude oil as the country’s biggest import.

Experts say Chinese chipmakers are five years behind their U.S. and Asian rivals and that increasingly high technological hurdles and a meager talent pool are hindering the effort to catch up with dominant U.S., Japanese, South Korean, and Taiwanese manufacturers.

As Chinese researchers and chipmakers strive to catch up, the technology is evolving, with new materials transforming the future landscape of the electronics industry. The latest advanced chips are highly complex to make because of increasingly tiny “nodes” that make them faster and more power-efficient.

Beijing has been backing up its towering ambitions in the semiconductor sector with money and tax breaks. The government set up the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund in 2014, seeded with 140 billion yuan ($22 billion) in capital to invest in chip companies. A second round of fundraising for as much as 200 billion yuan is underway, Chinese media report.

The state-controlled Tsinghua Unigroup project, associated with Tsinghua University — China’s equivalent of MIT — has emerged as a national champion. It’s building two massive memory chip factories, including a $30 billion facility in Nanjing that will churn out 100,000 wafers a month and is expected to exert a “siphon effect,” drawing microchip industry suppliers and experts to the area.

It’s unclear how successful those efforts will be as foreign regulators push back against Beijing’s strategy of acquiring overseas chipmaking-related firms. Washington has scuppered multiple China-linked bids for semiconductor-related firms following a call from a White House advisory panel to do more to protect the U.S. industry because of China’s industrial policies.

Market leaders like Samsung, Intel and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing are investing aggressively as they fight for market share.

“Even though they’ve (the Chinese) committed a lot of money to the investment fund, the reality has sunk in that it’s harder than just throwing money at the problem. The Samsungs of the world, the TSMCs have a large head start,” said Alexander Wolf, an economist at Aberdeen Standard Investments. “Certain products, you can’t really reverse engineer.”

Companies like Huawei and ZTE are avidly pursuing advanced semiconductor technology, but experts say overall Chinese research and development spending is a fraction of the multibillion-dollar budgets of the big players. That’s one reason Beijing’s success is anything but a given.

“These things are built from thousands of engineers of different disciplines pulling it together,” said Christopher Thomas, a Beijing-based partner at consulting firm McKinsey, who estimates it will take a decade for China’s efforts to result in any meaningful shift. “You’ve got to solve all the complexity to catch up. You can’t just solve one thing.”

What’s next?

Trade talks continue Friday, with more meetings scheduled before the U.S. delegation departs Beijing on Friday evening.

Trump said on Twitter at the start of the talks that he expected relations to stay on an even keel.

“Our great financial team is in China trying to negotiate a level playing field on trade!” he tweeted. “I look forward to being with President Xi in the not too distant future. We will always have a good (great) relationship!”

On Thursday, the U.S. delegation had meetings with U.S. Ambassador Terry Branstad at the U.S. Embassy then went to a state guesthouse for meetings with the Chinese, followed by dinner. There were no public statements from either side afterward.

The consulting firm Eurasia Group said in a research note that rival views in Washington, reflected in the makeup of the U.S. team, could undermine the U.S. negotiating stance.

“The U.S. delegation headed to Beijing is too large and unwieldy to accomplish much; it is a reflection of inter-agency rivalry on the U.S. side and this will produce more posturing than actual negotiations with the Chinese,” the firm said.

“The trip will produce few results and increases the risk that tariffs are adopted in the near future,” it added.

AP researcher Yu Bing contributed to this report from Beijing.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.