Two visions of African spirituality at the African American Museum

A photojournalist and a fine-art photographer collaborate on a dual exhibition of the Baye Fall of Senegal and the indigenous deities of Sierra Leone.

Listen 2:11

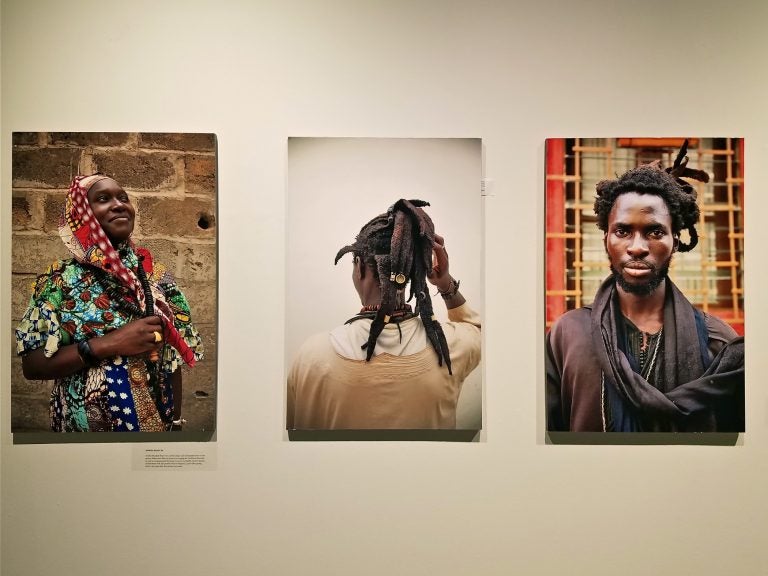

Laylah Amatullah Barrayn has been traveling to Senegal since 1999 to take pictures of the Baye Fall, a Sufi sect of Islam. Her images are on view at the African American Museum in Philadelphia in the exhibit, "Baye Fall: Roots in Spirituality, Fashion and Resistance." (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

The third-floor gallery of the African American Museum in Philadelphia is split in two, with a documentary photography show on one side and, on the other, a more imaginative show of staged and conceptual photography.

The photographers – Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Adama Delphine Fawundu – are from Brooklyn with African heritage. Two years ago, they founded MFON, a publishing project of African diaspora women photographers. Together, they coordinated this bifurcated show.

One side, “The Sacred Star of Isis and Other Stories,” is dominated by a large-screen monitor with a soundtrack of hip-hop samples and spoken word. The video by Fawundu, starring herself in the shower, begins with a slow-motion shot of her perfectly processed, straightened hair going under the showerhead.

It’s a slow, drawn-out moment of death and rebirth.

“Hair is a metaphor: ‘Oh my gosh! You’re destroying your hair!’” said Fawundu, who usually wears her hair naturally tightly coiled. “I got my hair straightened right before [the shoot] and the heat, the process – that’s destruction as well, you know.”

The video continues with Fawundu pouring milk through her wetted kinks – it’s white rivulets streaming down her back – and then fake blood. The video is filled with visual symbols of cleansing, sacrifice, and nurturing borrowed from her Sierra Leonean heritage and her Mende ancestors.

Fawundu grew up with the hip-hop of New York and the batik fabrics of her grandmother.

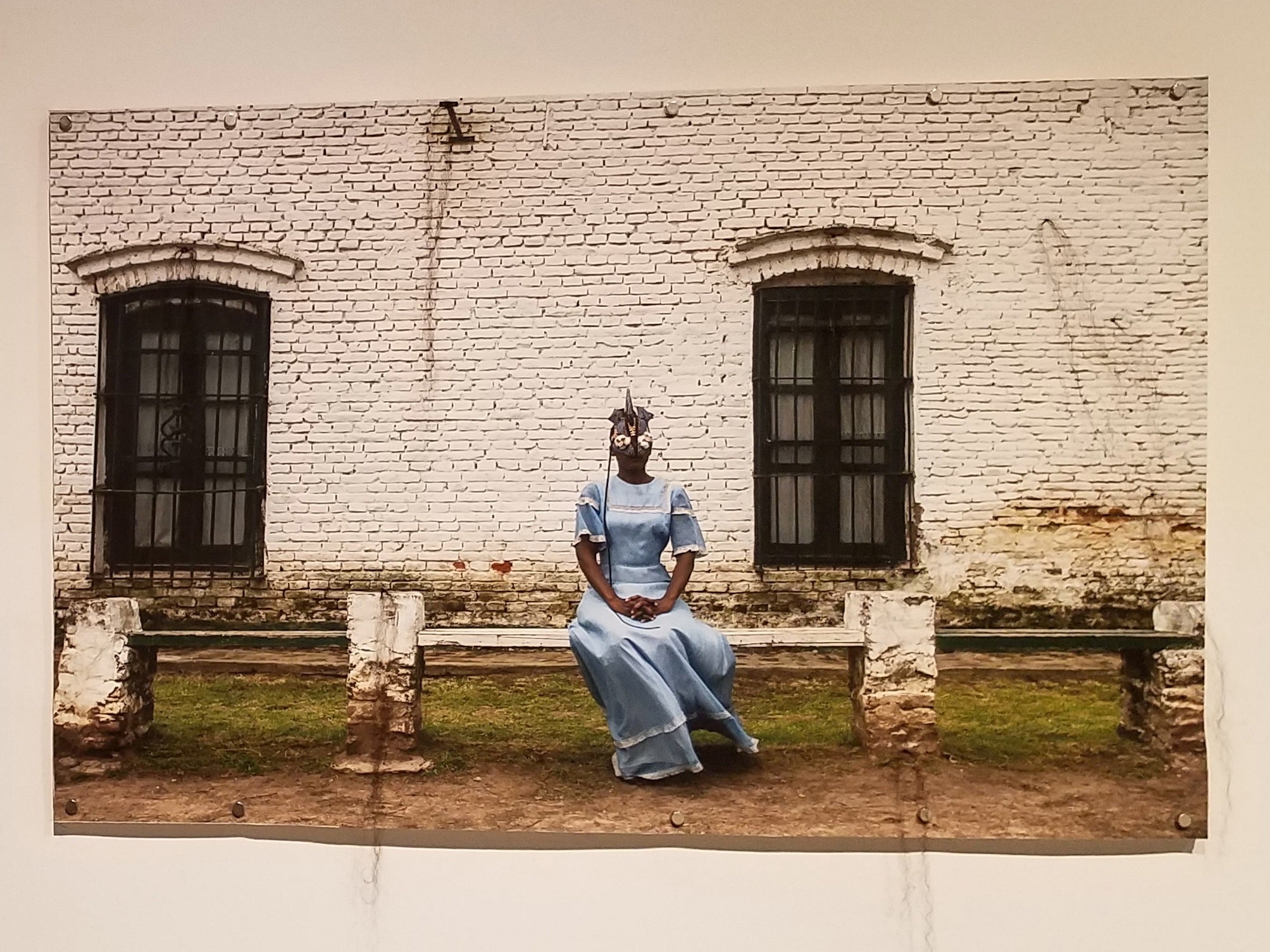

Much of the photography on the walls show Fawundu depicting masked West African deities — in particular the river goddess Mami Wata. According to Fawundu, Mami Wata sightings are frequent in Sierra Leone.

Focusing on the Baye Fall

On the other side of the gallery is “Baye Fall: Roots in Spirituality, Fashion, Resistance,” an ongoing photojournalism project by Barrayn. She has been visiting Senegal for 10 years to document the Baye Fall, a Sufi sect of Islam, whose followers often wear clothes of brilliantly bold colors.

Their sky-blue robes and patchwork slippers make them particularly photogenic. The fashion sense of the Baye Fall is deeply rooted in their religion. The 19th-century namesake of the movement, Ibrahima Fall, traveled throughout Senegal, depending on the kindness of strangers.

“People would give him different kinds of fabric, and he would make his own clothes from the fabric he collected,” said Barrayn. “For him, it was a matter of function, but now it’s become a matter of style.”

Barrayn grew up in Harlem, in a Turkish order of Sufism, and was always aware of the large population of Senegalese Baye Fall in New York. When she first visited Senegal, as a student in 1999, she quickly gravitated toward their familiar bright colors and distinctive singing.

“Baye Fall is the first community I was interacting with,” she said. “I was happy and surprised to come in contact with this collective.”

The split sides of the gallery exhibition are two ways to explore identity and spirituality in Africa, both seen through the lens of native-born Americans. While Barrayn captures the colorful spirit of the Baye Fall often on the streets of Dakar, Fawundu evokes the elusive spirit of Sierra Leone mysticism through patterns, masks, and scrims.

Fawundu puts herself in extravagant ball gowns, obscuring her face with a mythical mask of the Mende people. The skin of a contorted nude body on a bed coverlet is imposed with batik pattern. And then there’s the hair: processed, cleansed, reshaped, reinvented.

“I used myself to destroy the idea of identity,” she said. “Things I was taught, sometimes I want to throw it all out the window and rebuild again. If we constantly do that, we see ourselves differently. Maybe it makes us more human.”

“Baye Fall: Roots in Spirituality, Fashion and Resistance” and “The Sacred Star of Isis and Other Stories” are on display alongside a third gallery hung with selected works on paper from the African American Museum in Philadelphia’s collection. All three will be on view until May 12.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.