Trenton’s famed Mercer cars chronicled in a new book

If historic preservationist Clifford Zink could travel back in time, he’d have to make at least three stops in New Jersey’s capital city. He’d want to land in 1845, at the site of what is now Waterfront Park, where Peter Cooper started a rolling iron mill. “They were rolling the first I-beams in America,” said Zink. “I’d want to walk around that factory and see the steam-powered operations.”

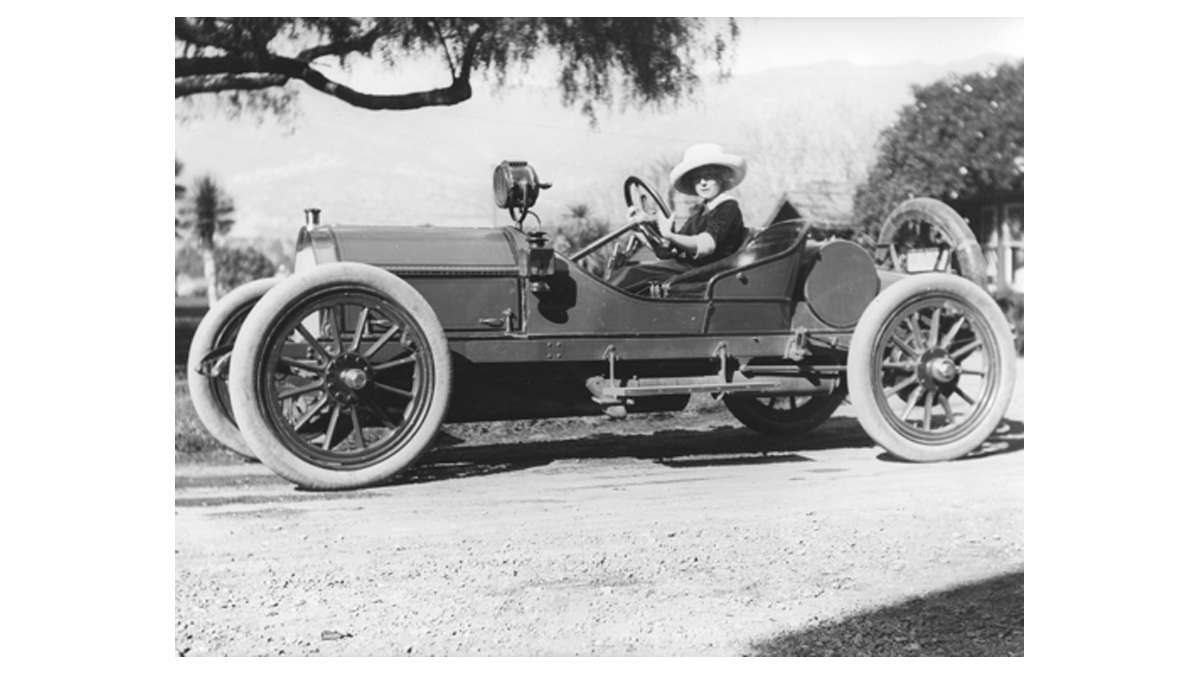

Next, he’d want to get off the time machine in 1849, to see Brooklyn Bridge designer John A. Roebling & Sons build the largest wire rope factory in the world. Today, Roebling Market occupies that space; Zink offers an historic tour of Roebling Iron Works each year during the annual Art All Night event in Trenton.His time travels wouldn’t be complete without a stop in 1912 at the Mercer factory on Whitehead Road. “They made about 500 cars a year—that’s about two a day—by hand,” said Zink. “They assembled the chassis, built the motors, tested them on blocks, did the upholstery, assembled and painted them and then test drove the vehicle.” In business for 15 years, the Mercer Automobile Company manufactured 5,500 vehicles; only 140 of the classic cars have survived. Many were hauled from barns and fields, melted and scrapped for metal during World War II.The Roebling Museum has just published Zink’s book, Mercer Magic: Roeblings, Kusers, The Mercer Automobile Company And America’s First Sports Car. Now a collectible antique, the Mercer auto was designed to be raced and won competitions across the country. On a gray wintry day, Zink arrives by bicycle at Princeton’s Whole Earth Center to talk about the car. He encounters a friend who is restoring old planes at the Princeton Airport, and Zink gets excited hearing about another relic worthy of preservation. The Bronx native who grew up in Bergen County and has lived in Princeton since 1972 has been fascinated by the way things were made, suspension bridges in particular, since he was 5. His family would drive into New York and the best part, for him, was the trip over the George Washington Bridge. “All the cars and trucks were held up by wires,” he marveled. “There’s something magical about suspension bridges. Old stone bridges have arches, and there’s a downward force supporting the load. In suspension bridges, the weight is collected by spans to the tops of the towers, where gravity forces it down to the foundation and the earth. But I didn’t know all this when I was 5.” Zink went on to write two books about the Roeblings and their legacy from the industrial age, made a film and helped to establish the Roebling Museum in the eponymous New Jersey town. As executive director of the Trenton Roebling Community Development Corp., Zink led the effort to turn the wire rope company facility into an urban center for culture and commerce. Zink’s interest in the car began in 2009, when the Roebling Museum held a reunion for Mercer collectors. He wanted to write about the Mercer, he recounted, because it was an unknown part of Trenton’s history. Collecting cars has become a good investment, as the value has gone up significantly in the last five years. “A lot of people who grew up in the 50s, 60s and 70s remember the golden era of American cars—Corvettes, Thunderbirds, Mustangs. They want to show their kids the cars they drove when driving was fun. Driving has become a routine activity, a hassle in traffic. Collecting is not only an investment and hobby, but a social activity and opportunity for connoisseurship.”Mercer Automobile was founded in 1909 by Charles and Ferdinand Roebling, sons of John A. Roebling, and their friends and business associates, Anthony and John Kuser. The Kusers focused on the finances of the business and the Roeblings took care of management and production.“Trenton was fertile ground for startups,” said Zink. Trenton had the same ingredients as Silicon Valley today: wealthy capitalists, manufacturing technology and a highly skilled workforce. Metal, rubber and pottery companies also required skilled workers, and when Mercer started, it represented a chance for young machinists with skills to move up. Companies retooled themselves to supply the auto industry, and Trenton became the top tire manufacturer until Akron, Ohio took that honor.The Kuser family also controlled the State Fairgrounds, where Grounds For Sculpture is now located and the horse track was turned into a track for racing cars. “Young men were excited by the new technology and speed,” said Zink. “Cars were expensive, and only the wealthy could afford them. Washington Roebling, then in his 20s, was one of these wealthy young men.”By racing the cars, it helped to “improve the breed,” said Zink, because any deficiencies that wouldn’t show up under a year of normal use would become apparent in a day at the track. “The public was enamored of racing a machine that never existed before; it was totally new technology that went at speeds no one had ever gone before. People thronged to races and newspapers gave publicity to the winners, proving that your car was durable and fast. They handled well, going around a turn on bumpy roads at 70 mph, or over 100 on a racetrack. People had never gone that fast before.”Zink had the opportunity to ride in a Mercer Raceabout owned by George Ott. “It’s completely open,” he recounted. “There’s no cover, no seatbelts, no heat or air conditioning—it’s a pure machine. The wind is blowing in your face, it’s noisy and you’re exposed to the elements, and you’re bouncing in the open-air seat. I don’t want to call it primitive, but there are no amenities, no protection. It’s a visceral experience, and gets you closer to what it was like to experience the auto when it was an entirely new technology.”Clifford Zink will give a talk about his book Mercer Magic: Roeblings, Kusers, the Mercer Automobile Company and America’s First Sports Car at the Princeton Public Library April 17. There will be a Mercer Auto Reunion at the Roebling Museum, Roebling, N.J., July 23.

_____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.