There’s no such thing as free parking in Philly, says economist who calculated how much off-street parking adds to housing prices

*In the audio above, Kevin Gillen is misidentified as a Drexel professor, but he is actually a “Senior Research Fellow.” We regret the error.

Parking is a perennially hot topic in Philadelphia, but in 2017 it appears to be heading towards supernova.

City Council President Darrell Clarke is pushing for a bill that would greatly increase the number of parking spaces developers would be required to build when constructing new housing. Parking concerns led city council to end a program that encouraged ownership of electric vehicles. Urbanist PAC the 5th Square is suing the city over the illegal, but popular, practice of parking in the middle of Broad Street in South Philadelphia. There are even political candidates who are running on that narrow, but extremely heated, topic. Almost every development fight begins and ends with parking.

That’s why Drexel University economist Kevin Gillen conducted a study for brokerage firm Houwzer, which tries to put a dollar amount on how greatly Philadelphians value parking and how that value differs across neighborhood and housing type.

“The question we tried to answer in a disinterested objective way — we had no agenda for a particular answer — is what is the real value in terms of dollars that Philadelphians put on parking,” said Gillen, who is senior economic advisor for Houwzer. “The problem is that people want it, but they want it for free. That may have been fine when we were a depopulated city, but now we are not.”

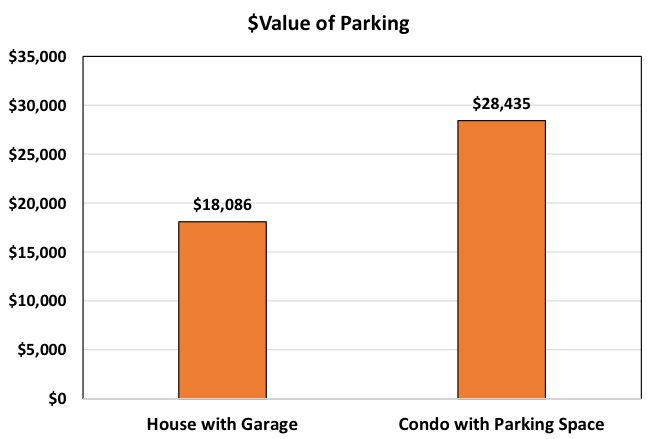

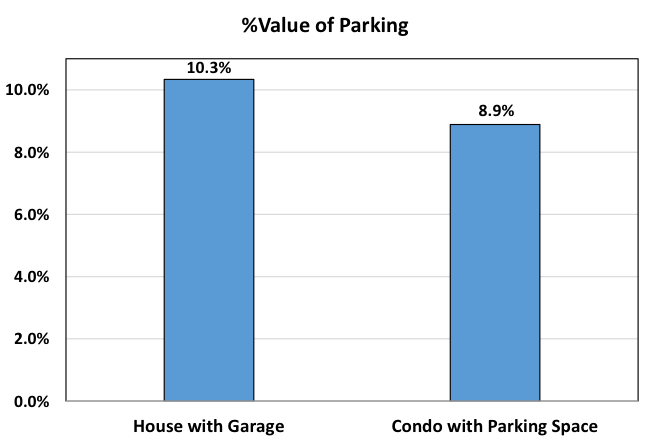

Gillen took house and condo sales across Philadelphia and compared the prices of units that come with garages or other forms of parking and those without. He controlled for differences in size, type, and age of the housing. Gillen found that the average difference between a home or condo with a parking space and one without is between $18,000 and $28,000.

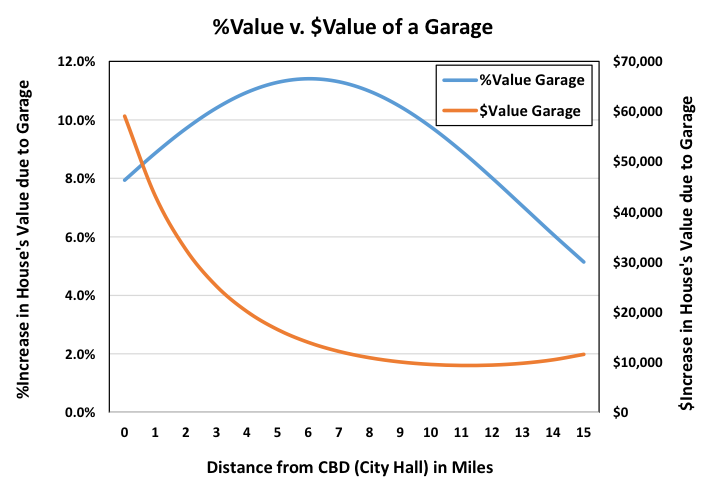

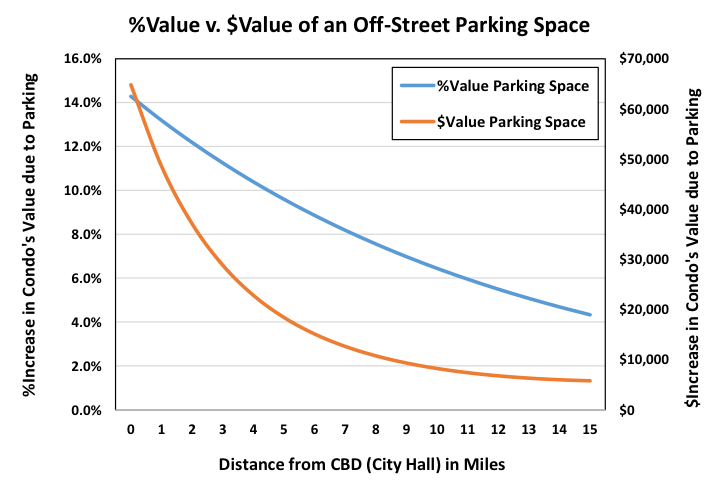

The results varying depending on the type of home. Parking spots add more to a condominium’s cost than a house’s price tag. The study shows that homeowners living three-to-eight miles from Center City have the highest preference for parking — they want, or need, parking the most compared to residents in the heart of Center City or in neighborhoods on the edge of town (where free parking is abundant). Meanwhile, the willingness of condo dwellers to pay for parking declines steadily the further from Center City they get, both as a percent of home value and in absolute dollar terms.

Unsurprisingly, Gillen found that a parking space for a housing unit in Center City is quite expensive in dollar terms, because that’s where real estate is most expensive. Gillen found a parking space within a mile of City Hall adds around $60,000 to its value (8 percent for houses, 14 percent for condos).

But as a percentage of the home’s total value, parking is valued most highly in rowhouse neighborhoods like Kensington, deep South Philadelphia, and the Lower Northeast.In some of these neighborhoods, adding a garage or another kind of guaranteed parking space to a home can increase its value by as much as 20-to-25 percent.

“Those are the places that have had no problem whatsoever with free on-street parking for decades,” says Gillen. “Now that those neighborhoods are revitalizing, it is becoming scarce.”

These neighborhoods have been the flashpoint in the parking fights that have become common of late. The rowhouse neighborhoods of South Philadelphia are home to the curious, and now besieged, practice of parking in the middle of Broad Street. City Council President Clarke largely represents older areas outside Center City and is pushing to ensure developers build more parking when they construct multi-family buildings. Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell attempted a similar bill last year and also represents a district consisting mostly of older rowhouse neighborhoods.

Gillen warns that the increased mandatory parking minimums supported by Clarke and Blackwell could have unintended consequences. Forcing developers to build more parking spaces when they build housing could put the brakes on new units, especially those that are more affordable for middle-to-working class people. Some projects simply won’t get built, while others will focus more on larger, luxury buildings so they can make up the additional cost by selling fewer units of higher priced housing.

Gillen noted that Oakland, Ca. enacted a similar parking mandate in the 1960s. A study showed that mandate increased construction costs, which were passed onto residents in the form of pricier housing. Parking mandates there pushed developers to build more high-end residences, and less affordable housing. “At the time of the change in its zoning law, Oakland was a predominantly blue-collar city with a housing stock disproportionately composed of modest attached rowhomes of workforce housing,” Gillen writes. “In other words, it was very similar to the Philadelphia neighborhoods that [Clarke’s] bill is intending to help.”

But Gillen said that he doesn’t envy City Council’s position. He doesn’t believe there are any easy options here and that all of them have serious downsides, be they political or economic.

“The logical response is that if people are placing an actual dollar value on something, but they are getting it for free, then you should charge them for it,” said Gillen. “We should be charging in the neighborhoods where demand exceeds supply of free on-street parking. How politically possible or palatable is that? I imagine it would meet with enormous resistance.”

Another option would be transitioning to less car-centric lifestyles, where residents in these neighborhoods own fewer cars per household and more frequently use transit, bikes, car share services, and their own two legs to get around. But Gillen said the possibility of such a lifestyle change is highly variable depending on which older neighborhood you live in. It is relatively easy to get to jobs and amenities without a car in South Philadelphia or University City compared to Mayfair or Olney.

Then there is the option which presumably most Philadelphians, elected or otherwise, would like to avoid: If neighborhoods lose population, the problem will solve itself.

“We could return to a city that is declining and depopulating,” said Gillen. “You know what city has tons of free on street parking? Detroit.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.