The Newark ark and its mysterious creator are revived at Philly’s Theatre Exile

The enigmatic story of Kea Tawana and her visionary, defiant ark is the basis of a poetic theater piece at Theatre Exile.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The story of Kea Tawana, the outsider artist who in the 1980s built a three-story ark on a vacant lot in Newark, New Jersey, is making its Philadelphia premiere this weekend at Theatre Exile.

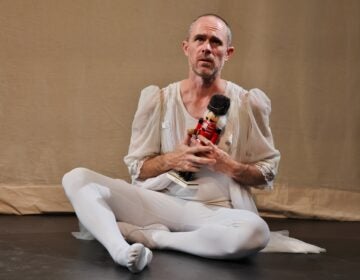

“Kea and the Ark” is an hour-long performance of theater, dance, puppetry and song that takes a poetic approach to the story of an enigmatic, itinerant laborer whose extraordinary creative vision to construct a 125-ton ark from reclaimed housing demolition materials became a political flashpoint in 1987.

The ark, which stood over 30 feet tall and stretched over 80 feet long, was never completed. Tawana worked solo, taking five years to build the structure by hand, using materials gathered from surrounding houses that were being razed by the city of Newark. The project and its controversy attracted national attention.

After a prolonged legal fight for which Tawana saw glimmers of victory, she ultimately acquiesced to the city and agreed to dismantle her structure. Ultimately, the bones of the ark were reduced to firewood.

“Here was a big move towards urban renewal and making the city shiny, and the ark wasn’t that,” said “Kea and the Ark” lead artist Sebastienne Mundheim. “So it went away.”

When audiences enter Theatre Exile’s basement space, the stage is cluttered with items, mostly constructed from paper and sticks, like an owl, a massive and shapeless black blob, a long crumple of red paper representing a sea of fire, a giant skeletal pack rat and a towering suit modeled after the boxy overcoat Tawana was often seen wearing.

But there is no ark on stage.

Instead of centering the thing for which Tawana is most known, Mundheim and her collaborators take a long, meandering walk through Tawana’s life before Newark, which is hazy. Tawana sometimes changed the facts of her life: She may have been born in Japan and grown up in an American internment camp, or perhaps on a Hopi reservation. She spent a lot of time living below the radar, relocating often to find work, likely moving by hopping freight trains.

Tawana’s shadowy life gives Mundheim plenty of wiggle room to create poetic interludes.

“Did this even really happen or was Kea a kid from Newark?” Mundheim asks in the performance, playing a storyteller. “Did she rip out the page of an encyclopedia? Did she find a piece of newspaper or an old National Geographic? Grab a little piece of conversation where she learned about the pack rat, internment, the Hopi and piece these stories together into a kind of coat, a garment of identity that she wore loosely at times?”

A miniature version of the ark appears toward the end of the performance, built by the performers out of other objects on the stage.

A more factual account of Tawana’s life came out in 2016, just months after her death, as an exhibition at Gallery Affero in Newark in partnership with the Clement A. Price Institute on Ethnicity, Culture, and the Modern Experience at Rutgers University. That was followed by a short documentary film, “Kea’s Ark” by Susan Wallner, which used archival video interviews recorded during Tawana’s lifetime.

“I worked in a marble quarry, then traveled on up through the mountain states working in the mines. Anywhere where I could find a job and they didn’t ask too many questions,” she says in the film. “I’m not a bit lazy.”

The meaning of the ark shifted the longer Tawana worked on it. The film suggests Tawana originally intended the ark to be seaworthy so she could sail it to Japan.

It became an act of political resilience. Newark’s Central Ward had suffered years of disinvestment and crime, which triggered a four-day riot in the summer of 1967, the so-called Newark Rebellion, resulting in 26 deaths and vast property damage.

By the 1980s, the neighborhood had not recovered. Then Mayor Sharpe James came into office with a vision of demolition and rebuilding. According to Newark Changing, a website using public data to track neighborhood evolution, 95% of Central Ward’s Belmont neighborhood was destroyed over a 40-year period, effectively erasing everything it once was.

Tawana’s process of repurposing razed buildings to build a beacon rising 30 feet in the air was a symbol of defiance for residents forced out by urban renewal.

“Her desire to find housing makes her a figure of our time,” said “Kea and the Ark” composer Daniel de Jesús. “This is someone who really believed in housing as a human right, but also fought for the housing of her neighbors and was building her own home out of the homes of people who lost their homes.”

The ark may also have been a compulsion. Tawana was driven to make things with her hands, and the ark served as a bottomless vessel to absorb that energy.

“It’s something about the rhythm of doing. She was a prolific maker of things,” said Mundheim. “I also get off on that kind of energy, of doing and sticking to your vision.”

Mundheim, a Philadelphia-based artist, had never heard of Tawana or the ark before she was approached by the Art Yard, an art presenting space in Frenchtown, New Jersey, with an offer to commission a piece. “Kea and the Ark” premiered there in 2023 and has since been to the Kohler Arts Center in Wisconsin, where Tawana’s archive is held, and Delaware Contemporary in Wilmington.

Mundheim and de Jesús were the first to sort through Tawana’s raw archives before they were cataloged, paging through stacks of notes, drawings, and collections, including rocks and bottles.

She discovered that Tawana kept all her supermarket receipts from Save A Lot and used them as notebook paper. On stage, Mundheim made a sail of Acme receipts.

“That’s where I shop all the time,” she said. “She was a collector and a very organized person. She wrote a lot of her journal entries and lists of things to do on the backs of Save A Lot receipts. So we started to organize all of our Acme receipts.”

Mundheim said she feels a kinship with Tawana as a person who makes things. The stage of “Kea and the Ark” is cluttered with things handcrafted by Mundhem and her collaborators, such as Harlee Trautman, who admires Tawana for pursuing a life both unusual and unapologetic.

“Kea took up space in a particular way, whether it was through her physical being or through the way that she engaged politically through the ark,” she said. “There’s something really inspiring about that, of just being without having to have an excuse or a reason.”

“I love that,” Mundheim chimed in. “The giganticness of her being. The insistence. It’s an incredible celebration about life, that you occupy it. You occupy your life regardless of the circumstance.”

“Kea and the Ark” runs Dec. 20–23 at Theatre Exile in South Philadelphia.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.