The provocative millionaire’s tax: Its potential (and past) in N.J.

Gov. Phil Murphy’s determination to try again for a true millionaire’s tax could make budget negotiations with fellow Democrats difficult.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy speaks during a joint meeting of the Democratic-led Assembly and Senate in Trenton, N.J., Tuesday, March 5, 2019. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

This story originally appeared on NJ Spotlight.

—

A renewed push by Gov. Phil Murphy to establish a true millionaire’s tax in New Jersey has the potential to rekindle a long-simmering debate about tax equity and fairness at a time when the state continues to struggle with income inequality. It also comes as new federal tax rules are fueling concerns about regional competitiveness and outmigration.

Murphy, a first-term Democrat, as part of his fiscal year 2020 budget proposal, wants lawmakers to go a step further than they were willing to go last year when they set a higher income-tax rate for earnings over $5 million. That helped fund spending increases on K-12 education, public-worker pensions and property tax relief.

This time around, the governor is seeking to extend the 10.75 percent rate down to earnings over $1 million, which currently are taxed at a rate of 8.97 percent.

The goal of Murphy’s proposal for a millionaire’s tax is to generate an estimated $447 million in new revenue to add to last year’s new investments. Administration officials have also noted in briefings that the new rate would deliver on a core campaign promise Murphy made in 2017 to establish “fairer” fiscal policies following the tenure of his predecessor, Republican Chris Christie.

But Murphy is already facing strong resistance from Republicans and top leaders from his own party, including Senate President Steve Sweeney (D-Gloucester).

Before Sweeney was against it, he was for it

Sweeney was once a prime sponsor of legislation seeking to create the same millionaire’s tax that Murphy is backing this year, but he no longer thinks it’s good policy given the federal government now caps the longstanding income-tax deduction for state and local taxes.

Disagreements over tax policy and the fear that higher rates would lead to outmigration nearly led to a government shutdown last year. But this year lawmakers are being encouraged to look more closely at the state’s entire income-tax structure, especially considering the last major changes occurred during the Great Recession when the state’s hand was forced by plummeting revenues.

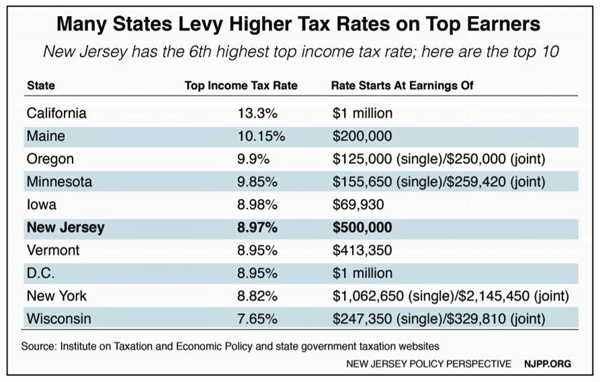

Currently, California has the highest marginal income-tax rate among U.S. states at 13.3 percent, according to data compiled last year by the Tax Foundation, a right-leaning organization based in Washington, D.C. In the Northeast region, New Jersey’s 10.75 percent top-end rate is the highest among its peers, although it isn’t triggered until an individual or couple makes more than $5 million in annual income. New York’s top-end rate is 8.82 percent, starting with income over $1.02 million for individuals. Next is Connecticut, at 6.99 percent for individuals making over $500,000. On the low end is Pennsylvania, which levies a flat income-tax rate of 3.07 percent.

But Murphy administration officials caution that state-by-state comparisons are difficult to make because in some places, like New York City, the levying of local income taxes and other policy differences can lead to distortions. They also note that half of the roughly 40,000 New Jersey tax filers who would be subject to a true millionaire’s tax in New Jersey live out of state and earn money here only through partnerships or other profitable occupations.

The 10.75 percent rate for top earners that Murphy has embraced is actually a remnant of a tax policy first put in place a decade ago by then-Gov. Jon Corzine as the state was in the grips of the Great Recession. As the global downturn triggered record revenue losses in New Jersey, Corzine, a Democrat, proposed increasing the top-end rate for one year to 10.25 percent as part of a broader plan to balance the budget for FY2010. Later on in the budget process, his administration came up with the proposal to levy a 10.75 percent rate for one year on earnings over $1 million.

More a matter of revenue than policy

The debate among lawmakers and administration officials at the time made it clear that the new policy wasn’t being driven by any stirring advice from economists or tax-policy experts, but more by a need to save a budget that was hemorrhaging revenue.

“It’s a balancing act,” said then-State Treasurer David Rousseau while appearing before lawmakers in 2009.

“The increase to 10.75 percent is giving us $200 million more,” Rousseau went on to say.

Since then, discussions about the millionaire’s tax have largely centered on its potential to bring in new revenue, with little focus on how the state should actually structure its tax rates and whether there should be an update to account for inequities that may have developed since the low point of the recession a decade ago.

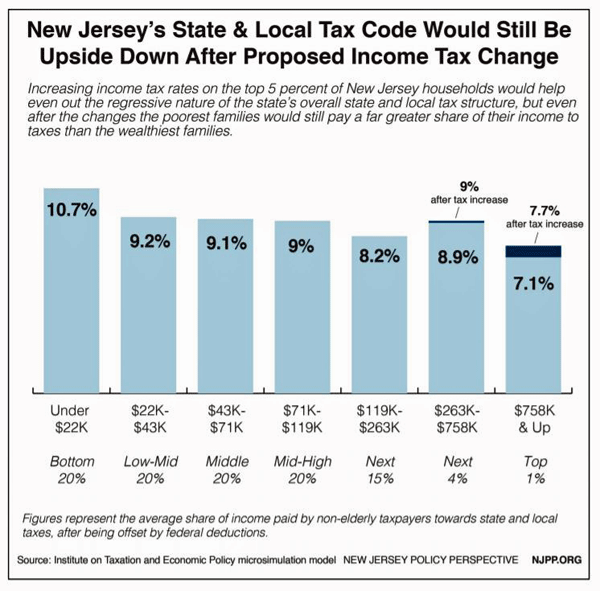

A recent proposal from New Jersey Policy Perspective, a left-leaning think tank that’s based in Trenton, included a call for the 10.75 percent rate to be applied to earnings over $1 million, but only as part of a broader overhaul of the tax brackets that the group is seeking to restore more equity and tax fairness. In fact, the group’s plan calls for a series of new rates to be established starting with those making $250,000 or more as a way to address a disproportionate share of wealth that’s held by those with the highest incomes in New Jersey.

A new Gilded Age?

“Right now, New Jersey’s top 1 percent make 24.3 times more than the bottom 99 percent,” said Sheila Reynertson, NJPP’s senior policy analyst. “These select few top earners take home 19.7 percent of all income in New Jersey.”

“Instituting a 10.75 marginal tax rate on earnings over $1 million is the very least lawmakers should do to make the tax code fairer,” she went on to say. “The real fight is restructuring the entire income tax code to better reflect the new Gilded Age we live in.”

A progressive income-tax structure which subjects taxpayers to higher rates as they report more earnings has also been highlighted by the Washington, D.C.-based Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy as a way to establish tax fairness across income brackets. The group released a study last year that found middle-income earners in New Jersey pay a slightly higher effective state and local tax rate than those in the top 5 percent. But it also found those in the lowest income brackets pay the lowest effective tax rates in New Jersey.

“This example shows that while state tax codes are not a cure-all for economic inequality, well-designed systems can help lessen the problem while steeply regressive systems only make it worse,” the ITEP report said.

Makes budget ‘more reliant on high earners’

Murphy’s FY2020 millionaire’s tax proposal has already been faulted by the Tax Foundation, whose analysis said the ideal state tax structure is one that features a broad base and overall low rates. It also noted the income tax is already New Jersey’s largest source of revenue.

“The millionaire’s tax violates principles of stability and neutrality while doing nothing to solve the state’s current problems with complexity and lack of transparency,” the analysis said. “It makes the state budget even more reliant on high earners, creating a more volatile source of revenue.”

John Boyd, a principal at Princeton-based The Boyd Company, a leading corporate-site consultant, also suggested New Jersey policymakers should be careful about applying the 10.75 percent rate on earnings over $1 million given the state already has a reputation for levying other high taxes. Executives in industries like banking, pharma and tech take a close look at marginal income-tax rates when they’re looking at places to set up shop.

“It is a major site-selection factor for the types of projects that New Jersey is competing for,” Boyd said.

He also pointed to an ongoing debate in New York, where Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo is pushing back against calls for higher taxes on the wealthy, echoing some of the same arguments now being made by Sweeney across the river in New Jersey.

“Phil Murphy pursuing this millionaire’s tax now does not show good economic-development acumen,” Boyd said.

Last year, Murphy was asked why he was pressing for a rate of exactly 10.75 percent after lawmakers had countered in the middle of budget negotiations with 9.95 percent as a way to stay under the 10 percent threshold. In response, he told reporters there was “no magic” to the higher rate. But he added such a rate would generate a “significant resource” for the budget that could fund programs that benefit the middle class.

“I think it’s not in excess. It’s not so much that you can say you’re declaring tax warfare,” Murphy said. “We don’t want to do that. We want folks to say no matter what their circumstances are that, at the end of the day, this is all about equity.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.