The history of submarine warfare off the Jersey coast

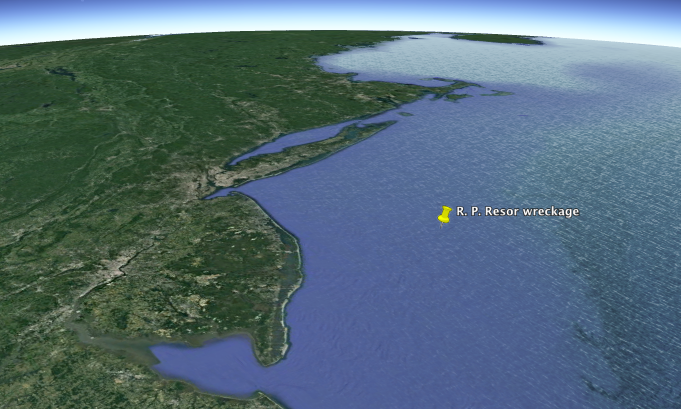

The R. P. Resor was torpedoed on Feb 28, 1942 off the coast of northern New Jersey, with a full load of crude oil. (Photo courtesy of Joseph Bilby)

Imagine yourself on a beach in Sea Isle City in the winter of 1942. It’s night, and a cold, steady breeze off the Atlantic numbs your nose. The shock and horror of the attack on Pearl Harbor remains fresh and raw as you look out toward a distant orange glow on the horizon.

You know it’s an American ship, probably an oil tanker from how long that fire has been burning out on the open ocean. It’s the opening days of America’s involvement in a war that has already spread around the world, with dire, implacable enemies to the east and the west. Even as thousands volunteer to fight in Europe, Africa and the Pacific, war has come to our shores.

U-boats prowl the dark waters.

Well before America declared war on Dec. 8, 1941, German submarines, or unterseeboote, ranged the North Atlantic, seeking to cut off trade and starve the defiant British. Once the United States entered the war, it became open season for U-boat captains on ships off the East Coast. From January of 1942 until August of that year, German torpedoes sunk a dozen or more shifts off the coast of New Jersey, with many more attacked off North Carolina, Virginia and the Gulf of Mexico, according to Joseph Bilby, a New Jersey military historian and author.

Many of the ships were attacked within a few miles of the beach, he said. By day, thick black smoke could be seen belching into the sky as the ship burned and sank, while at night, the glow from the flames could be seen from along the coast. World War II was being fought right along the Jersey Shore, leaving beaches strewn with washed up oil, wreckage and occasionally the body of a sailor.

The sinking of the R.P. Resor

Local newspapers at the time included accounts of the wrecks, describing the glow visible in the distance. When the German submarine U-578 torpedoed the tanker the R. P. Resor off of Manasquan with a full load of crude oil on Feb. 28, 1942, a newspaper commissioned a boat to carry a reporter and photographer out to the ship, Bilby said in a recent interview.

“You could see the fire all the way up to Belmar,” Bilby said. There were only two survivors, Seaman John Forsdal and Coxswain Daniel Hey.

One memorable report in a shore town weekly paper at the time reassured residents not to worry about the balls of tar washing up on the beaches. It was only oil spilled from the sunken tankers.

According the Bilby, the British warned the Americans about the likelihood of submarine attack. But for half of 1942, most ships remained defenseless against the unseen torpedoes. There had been naval attacks off the New Jersey coast in World War I, Bilby reported, but while that war is best remembered for intractable trench warfare and the widespread use of poison gas, in these cases the submarine captains were reluctant to torpedo civilian craft. In one case in 1918, the sub surfaced and demanded an ocean liner surrender. A German officer evacuated the crew and passengers before scuttling the ship.

A generation later, things were not nearly so genteel. Ships were sunk from under water as military and civilian officials scrambled to respond. By late summer in 1942, civilian ships traveled with navy escorts and air support, including sub-spotting blimps from the Lakehurst base. The Army Air Corps began to coordinate with the navy while America scrambled to build coastal defenses. The U-boats began to concentrate on convoys heading to England.

Those months before America found an effective defense against submarine attacks were known to the German submarine crews as the “happy time,” according to Bilby’s book and several other sources.

Protecting the Delaware Bay

“After the war, we found out that the Germans had thought blocking the mouth of the Delaware Bay was crucial to the war effort,” said Dr. Bob Heinly, the director of museum education with the Cape May-based Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts and Humanities. Upriver lay the Naval Shipyard in Philadelphia, the Frankford Arsenal and refineries preparing the high-octane fuel needed for combat aircraft. “It was very important as they saw it to try to put a cork in the bay. There were 18 ships that we know of that were sunk in and around the mouth of the Delaware, many within sight of land.

“It was not an uncommon sight for people here in Cape May to see the smoke or the fire of a burning ship,” Heinly said.

The arts center, also known locally as MAC, is the group that preserved and restored one of the coastal spotting towers from the time. The concrete tube on Sunset Boulevard just outside of Cape May was one of several used during the war to watch the bay and ocean. MAC has turned Fire Control Tower no. 23 into an interpretive museum.

Along with a gun emplacement nearby known as Battery 223 and a more extensive array across the bay in Delaware, these emplacements were known as Fort Miles.

“Early in the war, before we knew any better, we feared an invasion of surface ships and an amphibious assault. Fort Miles was an army base, not a navy base, but almost as soon as it was built we realized that subs were going to be the problem.”

On the Delaware side, where the deepest channel in the bay is still used by oil tankers and huge container ships today, the larger batteries included 16-inch guns ready to go toe-to-toe with a German destroyer but almost useless against submarines.

During the war, the Army Corps of Engineers dug the Cape May Canal to allow safer passage for boats using the Intracoastal Waterway. The Navy base in Cape May – now the national training center for the Coast Guard – became a center for anti-submarine efforts by the Coast Guard and Navy.

Soldiers on horseback and Coast Guard officers patrolled the beaches, searching for landing spies and saboteurs. Local stories abound of aid and supplies given to the submarine crews by Nazi sympathizers and others. The Germans did try to land agents on Long Island, N.Y., according to Bilby, but there is little reason to believe most of the stories.

“There’s a lot of folklore about it. There are crazy stories about guys coming in and going to a local restaurant for something to eat,” he said. One persistent but unsubstantiated tale reports a German sailor taken prisoner was found with a movie stub from a Stone Harbor theater in his pocket.

U-578 spots destroyer

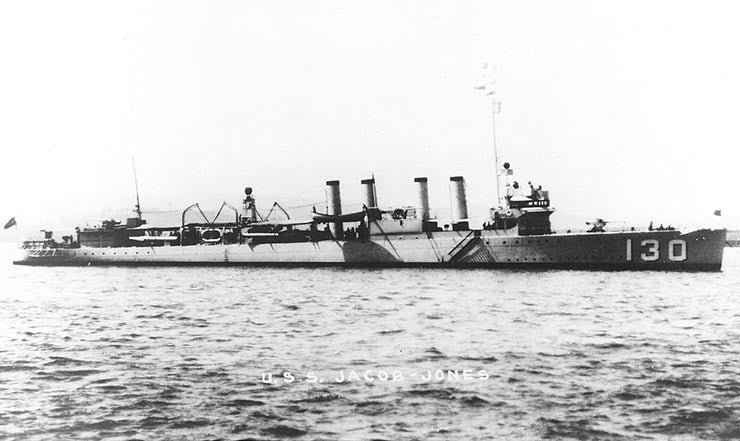

The same U-boat that sunk the R. P. Resor on February 28 off the northern Jersey coast was still on the prowl. The next morning just as sun began to rise the Germans spotted the USS Jacob Jones, a destroyer sent out to find the German sub that took out the Resor. The destroyer and the sub were about 25 miles off the coast of Cape May when the Germans fired a spread of torpedoes, hitting the port side. The destroyer didn’t go down right away but after nearly a hour the Jacob Jones plunged bow first into the waters. There were a few survivors, but only 11 made it to shore alive.

At the end of the war in 1945, many of the Germany’s surviving U-boats returned home but some like U-858 took their chances by surrendering to the allies. In this case, when the submarine surfaced and signed her intentions of surrendering it was off the coast of New Jersey. U.S. Navy personnel decided to hold the surrender ceremony over the wreck of the Jacob Jones and ordered the sub to those coordinates.

“The big formal surrender was an international news story,” Heinly said, with blimps and helicopters on the scene for the first U-boat surrender. On May 14, 1945, the German sailors became prisoners of war while an American crew brought the sub to Lewes, Del., which had a deep enough harbor to accommodate it. That closed era of submarine combat in New Jersey.

Underwater battlefield

Under the water, the sunken ships of both sides also remain. Gregory Modelle, a Somers Point architect and avid scuba diver, has visited the wreck of the Jacob Jones and other ships sunk by U-boats. Like other shipwrecks, the Jacob Jones is now little more than a mound of debris.

“It was really blown to pieces,” Modelle said. Slammed by the torpedoes, the ship was further torn apart when the depth charges on board exploded as it sank. A few things remain recognizable on these wrecks; an anchor, a propeller shaft. Boilers were built for extreme pressure, he said, so they often remain, and ceramic and glass won’t corrode in the salt water as does steel.

“Anything brass is still there. All the navigation equipment. These things are highly sought after by wreck divers,” he said. “I always look for portholes.”

In 1991, divers found what they later learned was the wreck of U-869, a German submarine formerly thought to have been sunk off Gibraltar. Modelle has never visited that wreck, which sits at a dangerous 240 feet below the surface, but he has sketched the wreck based on video captured by another diver. The outer skin quickly rusts away, he said, leaving the ribs and the pressure hull visible.

Like the other wrecks, Modelle said, the submarines are now home to lobsters and other sea creatures seeking shelter, acting like a steel reef on the silty bottom of the sea.

Joseph Bilby is the historian at the New Jersey National Guard Museum in Sea Girt. He is set to speak about the history of submarines off New Jersey at the next meeting of the Historical Preservation Society of Upper Township 7 p.m. Oct. 9 at the Upper Cape branch of the Cape May County Library, 2050 Tuckahoe Road.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.