Timeline: The Delaware River and the Clean Water Act

Reviving the Delaware River took decades and came about through a combination of social need, public outcry, and political will. Here, we look at the river's history.

Reviving the Delaware River took decades and came about through a combination of social need, public outcry, and political will. Regional efforts like the formation of the Delaware River Basin Commission helped bring the issue of water quality to the forefront, but nothing quite had the impact of the Clean Water Act, which not only regulated what could go into the river but also offered federal dollars to fix the problems.

Here, we look at the history of the Delaware River and its watershed through the eyes of the Clean Water Act.

1880s to early 1900s: The Delaware River as the Nation’s Shad Capital

Shad were once plentiful in the Delaware River, and shad fishing was a valuable regional industry. At the turn of the twentieth century, approximately 16 million shad were caught each spring on the Delaware River, with an income value of $149 million in today’s dollars.

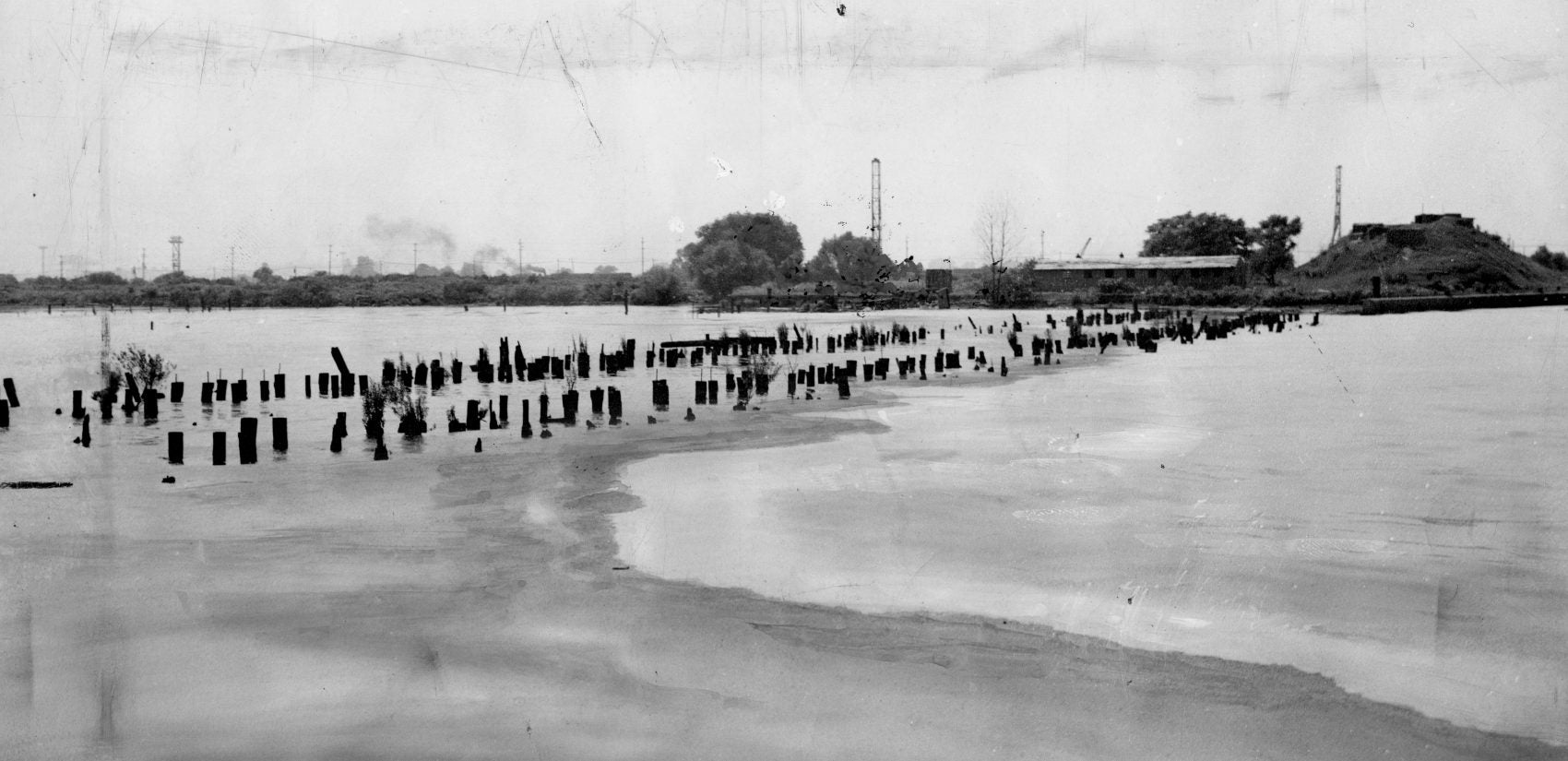

1920s: Pollution Kills the Fish

By the 1920s, shad had been nearly eliminated due to pollution and overfishing. Cities were dumping their sewage directly into the river, and the bacteria in that sewage gobbled up all of the oxygen in the water, leaving little to none for fish and aquatic life, particularly between Philadelphia and Marcus Hook.

Migratory fish like the shad would die before they could reach the upper Delaware to lay their eggs — and if they somehow made it through, the baby fish wouldn’t be able to make it back down river. Other fish like herring and bass also died off due to lack of oxygen and pollution.

1940s: A River You Could Smell from the Sky

During WWII, industries along the river ramped up production to aid the war effort, and any efforts to improve sewage treatment were tabled, as money was tied up in funding the war. Personnel of both Russian and British naval vessels complained that the odor of the Delaware made it impossible for them to eat their meals while docked there. A US Army pilot claimed he could smell the river from 5,000 feet in the air.

1961: The DRBC is Formed

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed the Delaware River Basin Compact creating the Delaware River Basin Commission. It included all four states — PA, NJ, NY, and DE — as well as the federal government, making it the first federal-state organization to address river planning, development and regulation.

The DRBC rolled out programs to regularly test the river for pollution and set goals and standards for industry and municipal wastewater treatment plants. However, many of the plans were hampered by a lack of federal funds.

1969: A River Catches Fire

In 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio caught fire after sparks from a passing train lit oil-slicked debris ablaze. The river had, in fact, caught fire many times in the preceding decades, but by 1969, a growing populist environmental movement was afoot. Many cite the 1969 fire as the turning event that forced Congress to pass the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act.

1970s: Change Comes Fast

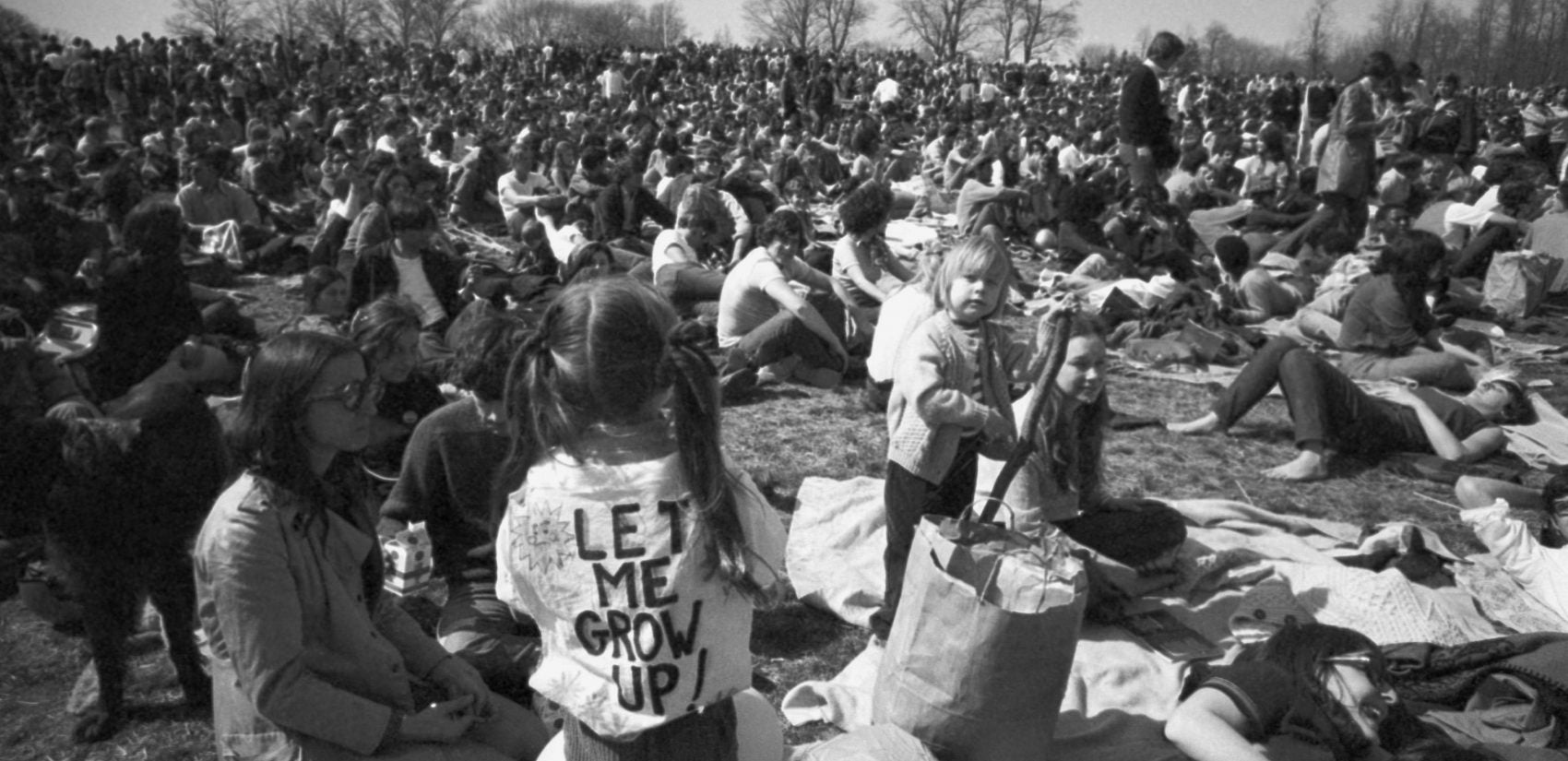

In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed a bill creating the EPA. On April 22 that year, some 20 million Americans celebrated the first Earth Day in rallies across the country, demanding policies for a clean environment.

Two years later, Congress passed the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments, which together became known as the Clean Water Act. President Nixon vetoed the bill, but within a day the House and Senate overrode the veto and the bill became law.

The law made it illegal to dump any pollutant into waterways without a permit from the EPA and set wastewater standards for industry. It also required wastewater treatment plants to upgrade to secondary treatment — meaning disinfection — and created a program whereby the federal government would fund 75 percent of those upgrades.

1980s: Sewage Plant Upgrades

Between 1981 and 1986, Philadelphia’s Southeast and Southwest sewage treatment plants were upgraded to secondary treatment, using biological science to treat wastewater before discharging it into the river. The Northeast treatment plant had already been upgraded in 1951.

Today: A Cleaner River…with Risks You Can’t See

Today, the state of the Delaware River has vastly improved. No longer rancid-smelling and covered in scum, the river draws tourists and locals for regular festivals and events along the waterfront. Fish like shad and bass have returned, and some fishermen say 2018 was the best shad run they’ve ever seen. The Delaware River Waterfront Corporation has raised nearly $30 million for capital projects to develop the waterfront into a destination. But despite the improvements, there are new threats to water quality, ones that can’t be seen with the naked eye. So-called contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) like pharmaceuticals and personal care products, PFAS/PFOA, and microplastics, as well as the overarching menace of climate change, all jeopardize the water quality in the Delaware, and the Clean Water Act does not address any of those concerns.

Read more:

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.