The Battle of Germantown: a ‘surprise’ that almost worked

The re-enactment of 1777’s Revolutionary War Battle of Germantown that will take place this Saturday is always a colorful spectacle. Re-enactors in Continental and British uniforms re-stage the pivotal clash at Cliveden of the National Trust, 6401 Germantown Avenue, that turned what seemed to be the early stages of a great American victory into a loss that left the British in possession of the field and the Americans in retreat. But the spectacle alone gives little in the way of clues to the how and the why of the battle, and how it fits into the larger picture of the War of Independence.

Historian Thomas McGuire will be remedying that lack at Cliveden at 11:15 a.m. and 2:15 p.m., as he speaks on “The Surprise of Germantown,” the title of the book on the battle that he published in 1994.

McGuire, who teaches history at Malvern Prep, is well-equipped for the task. He’s also the author of “The Philadelphia Campaign,” a comprehensive two-volume account of the British effort in 1777 to deal the rebellious colonies’ war effort a decisive blow by smashing the Continental Army under George Washington and capturing Philadelphia. (In the end, they were to succeed at one aim and fail at the other.)

In an interview this week McGuire indicated that British General Sir William Howe’s decision to move on Philadelphia might have been influenced by European ideas of warfare.

Plans for 1777

In 1777, he said, “Philadelphia was the principal English-speaking city in the Americas and also technically the capital [of the newly-declared United States of America]. In Europe, if you capture the enemy’s capital it generally means the end of the war. What Howe is going to discover is that isn’t the case here.”

But he did capture the city, though in a somewhat round-about fashion, taking his army by sea from its base in New York City. New York had been held by the British since the summer of 1776, when in a series of battles they’d chased Washington’s troops out of the town and across the Hudson.

The British ships sailed around the Virginia Capes and up Chesapeake Bay, where Howe’s soldiers disembarked at what is now Elkton, MD in late August, 1777. They began their march on Philadelphia on September 3.

Washington’s Continental Army came out to try to stop them. The Continentals were defeated at the Battle of Brandywine near Chadd’s Ford on September 11, and the entire army was nearly cut off and captured. “Howe had almost done that in the New York campaign,” said McGuire. If he had succeeded this time it would have been a body-blow to the American cause, he added, because after two years of a war that had begun at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts in 1775, “The Continental Army itself was carrying the force and life of the revolution.”But despite Howe’s failure to bag Washington and his army the way to Philadelphia lay open, and his troops marched into the city on September 26. They would remain there for most of the next year.

Why fight at Germantown?

Howe spread most of his army in a wide arc throughout Germantown, then a farming village five miles from Philadelphia. They stretched from what is now Market Square and along Schoolhouse Lane at the now-5500 block of Germantown Avenue (then known as the Great Road) to Mount Airy, the estate of Pennsylvania Chief Justice William Allen located at today’s site of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. There were about 9,000 men – British regulars and Hessian mercenary troops – in lines about two miles long that guarded the few roads into Philadelphia from the north and west.

Washington, encamped with his 12,000 men about 15 miles northwest of Germantown, thought he saw a chance to deliver a hard blow to the spread-out British, and devised a complicated and daring plan of attack. “He put the plan together in about 48 hours,” said McGuire, “It was so audacious it took the British by surprise. That it almost succeeded – that’s really the most remarkable thing about it.”

An ambitious plan

Washington split his army into four columns that would converge on Germantown from different directions in a night march. The bulk of the army, led by Washington’s best general, Nathanael Greene, would march along what is now Skippack Pike and Church Road in Montgomery County to Old York Road, then turn south to head for the main British encampment at Market Square. Another column, under generals John Sullivan and Anthony Wayne and accompanied by Washington himself, would head down Germantown Avenue from the direction of Chestnut Hill and try to roll up the British troops along the avenue. A column of militia on either flank would guard the sides of the two main columns. If everything went well, all the columns would meet in the middle of the British lines, attacking from two directions at once and capturing or destroying the lot.

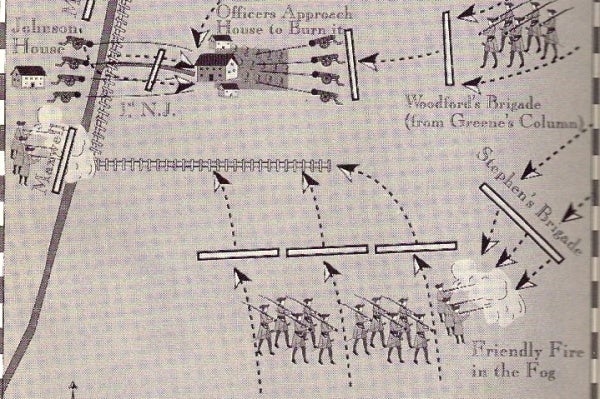

Everything did not go well. Greene’s force took the wrong road and took longer than expected to reach its assigned position, while the militia columns on either side did little to bother the British. But the force moving down Germantown Avenue was in place on time and attacked at daybreak on the foggy morning of October 4, flanking the first British troops it met (near what is now the intersection of Allens Lane and Germantown Avenue) and forcing them back down Germantown Avenue toward Cliveden, the summer home of Benjamin Chew and the grandest house in the area. A company of British soldiers – perhaps 100 men – barricaded themselves in the house as most of Washington’s force, under the command of General Anthony Wayne, passed on down Germantown Avenue toward the main British camp. Meanwhile, Greene’s men, though late, had reached their objective and were ready to attack. Then came a moment that’s a perfect example of the old saying, “a little learning is a dangerous thing.”

The turning point

Washington’s artillery chief was Henry Knox, who had performed yeoman service for the American cause in the past and would do so again in the future. Knox had transported the cannon captured by the Americans at Fort Ticonderoga to Boston in the winter of 1775-76, where Washington’s army used them to force the British to evacuate the town. He would later become the country’s first Secretary of War during Washington’s presidency.He was a bookseller by trade and entirely self-taught in military matters, mostly from the books that he sold in his Boston shop. In one of them he had read that it was unwise to leave a “fortified castle” in an army’s rear.Cliveden was scarcely that – a few companies of troops could have kept the British bottled up in the house. But Knox’s views carried the moment, and full scale assaults were mounted on Cliveden. Waves of attackers tried to storm the house and were beaten back.

Meanwhile, Wayne and his men, who were nearing the main British camp, heard the firing there and guessed that the British were counterattacking. They reversed their course and headed back to Cliveden. When they got there they ran into some of Greene’s troops, who were unable to identify them in the fog and gunpowder smoke that blanked the area. Greene’s men opened fire on Wayne’s, badly disordering both forces until the mistake was discovered.

The countermarch by Wayne and the disorder cause by the friendly fire gave the British in Germantown time to rally. Their successful counter-attack forced the Americans to retreat to Whitemarsh. The Americans suffered about a thousand casualties in killed, wounded and missing, while the British had about half that many.

Aftermath

Washington’s men, though beaten at Germantown, came away with a better opinion of themselves. “Morale was higher, it gave them the hope that they could in fact push the British Army back in a battle,” said McGuire. “It was one of those small things that had to do with sustaining the war effort. Even though we lost the battle it affected the army in a positive way.”

The Continentals would need all the positives they could muster in the coming months, since after inconclusive skirmishing with the British at the Battle of White Marsh in December, 1777 the army went into winter quarters at Valley Forge. The privations of that encampment – disease, famine, cold -winnowed the ranks from more than 12,000 who were at Germantown to fewer than 5,000 effective soldiers by winter’s end.

Meanwhile in Philadelphia, the British Army was nearly forced to evacuate the town before it had really settled in – not because of battles, but because of hunger.

Fort Mifflin (near what is now Philadelphia International Airport) was built by the Americans to control access to the town via the Delaware River. Until Fort Mifflin was captured by the British on November 15, little food or other supplies could reach the town. (Its defenses were one of the reasons Howe had sailed to Chesapeake Bay rather than directly on Philadelphia). “If the British hadn’t taken Fort Mifflin they’d have had to evacuate the city,” said McGuire.

But they stayed until next summer before marching back to New York City to join the main British army in the Americas. Their capture of Philadelphia had not brought the rebellion to a halt, but it did make for a difficult winter for the city’s 25,000 people.

Food and firewood were in short supply – though the river was open to the British not much was coming in from the countryside – and prices were high. “Once the British fleet was able to get up to the city, people who had means could live pretty wall,” said McGuire. “If you didn’t, it was hard.”

Germantown itself had been devastated during the fighting. While few houses other than Cliveden itself were badly damaged, McGuire noted in “The Surprise of Germantown” that, “Crops were trampled and smoldering in places, parcels of dead and wounded soldiers littered the landscape, ruined and broken fences lay shattered by gunfire.”Only one civilian is known to have been killed in the fighting. “Most people with sense headed for their cellars when the shooting started,” said McGuire. But even in 1777, boys would be boys. “There are reports that teenage boys would climb on the roofs of their houses to watch the fighting” he said.

McGuire said that one of the goals of his presentation at Saturday’s re-enactment is to impress upon his listeners that “What they’re seeing on a very small scale is just a glimpse of what these armies were like. “War has not changed though the technology has changed … as time passes you can romanticize it, but think of what you’re seeing on TV these days when a bomb goes off in a marketplace in the Middle East. That’s what this was like here. Nothing has changed, war is still war.”

What if?

Washington’s plan at Germantown had almost worked – for several hours on the morning of October 4 the Continentals had had the British on the run. What if it had worked? Would it have shortened the War of Independence? It’s impossible to say for sure, but it might have.

“Speculating is always dangerous, there are too many variables,” cautioned McGuire. But, he added, “While the plan itself was so unwieldy it couldn’t have gone like Washington had planned, there’s a good possibility that Howe’s army could have been forced out of Germantown. If they had been able to defeat the British Army there it would have been an utter disaster for the British. It would have been two major defeats for the British in 1777.” That was because at almost the same time that Washington was trying to destroy one British army, the Americans in New York state did surround and capture another under General John Burgoyne that was invading the colonies from Canada down the Hudson River. That victory during what’s known as the Saratoga campaign (and coupled with Washington’s bold near-miss at Germantown) was the major reason that the French under King Louis XVI decided to ally themselves with the rebellious colonies.

“Saratoga convinced the French that the American cause could defeat the British,’ said McGuire. “And ‘Washington is audacious’ was the French view of him after Germantown. It really took some brass for him to try to snatch victory from defeat.”

Without the French alliance, most historians have concluded, the cause of American independence would have been far more difficult – perhaps impossible – to achieve. French aid in men, money, arms and ships was vital. As it was, a rebellion that began in 1775 did not become a successful revolution until the climactic victory at Yorktown in 1781, four years after the carnage at Germantown.

For more information – Revolutionary Germantown Festival

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.