Television weather forecasts should get serious about climate change

Listen

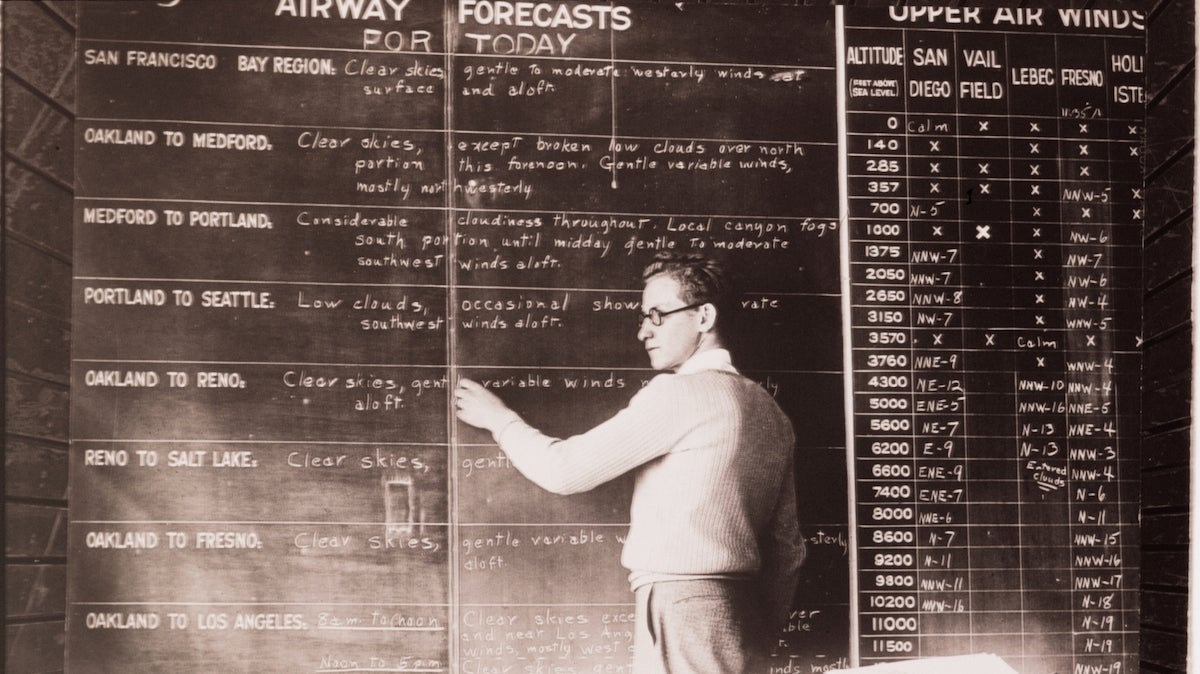

Early forecasts were geared primarily to military use and commercial aviation. (Credit: NOAA)

According to the American Meteorological Society, we have “unequivocal evidence” that “human activities” — especially the burning of fossil fuels — have changed the Earth’s climate since the 1950s. But you rarely hear a weathercaster acknowledge it on the air.

News Anchor [in a hopeful voice]: So will you bring us some sunshine tomorrow?

Weathercaster [grinning]: Well, I can’t promise anything. But I’m working on it.

Welcome to a standard news program in the United States, where weathercasters serve as our goofy national soothsayers. They’re screwballs, all right, donning ridiculous hats and delivering wacky one-liners. But they’re also trusted oracles who employ the latest scientific wizardry to divine the mysteries of the skies.

So why won’t they discuss the science of climate change, too?

With clear evidence that human activities are changing the climate, the White House is trying to change that reticence. Last month, President Obama invited eight weathercasters to discuss a new national report on climate change. Citing floods and wildfires, Obama stressed that climate change is “a problem that is affecting Americans right now.” And he called on weathercasters to emphasize the same.

I hope they do. But that will also require them to shed their jolly, happy-go-lucky style of journalism. Put simply, the weather has gotten serious. And we need our weather reporters to follow suit.

They might start by looking at weathercasters after World War II, at the dawn of American television. Many of them had served as meteorologists in the military, providing crucial weather information before invasions in Normandy and Okinawa. Not surprisingly, they brought a straight-laced, no-nonsense spirit to the screen.

Then came the 1948 freeze on station licensing by the Federal Communications Commission after worries that the proliferation of new TV stations was clogging the country’s frequencies. But the number of televisions in American homes continued to soar, from 3.6 million in 1949 to 21.8 million in 1952.

The FCC lifted its freeze that same year, sparking another boom in new stations. By 1955 there were 408 TV stations in the United States, up from just 108 in 1952. Most cities now had multiple stations, which competed furiously for viewers.

Weather ploys brought rating joys

And a good way to do that was to spice up weather reports. So stations introduced gimmicks, including a puppet who presented the forecast in St. Louis and a Nashville weathercaster who spoke in rhyme. “Rain today and rain tonight,” he rhapsodized. “Tomorrow still more rain in sight.”

The stations also hired “weather girls,” attractive young women who appeared in svelte outfits. Future Hollywood starlet Raquel Welch got her start as Raquel Tejada, the “Sun-Up Weather Girl,” on a San Diego news show. One woman gave the forecast in her bathing suit; another reported from inside a huge tub of water, drawing weathercast maps on its Plexiglas sides.

By the late 1950s, the gimmicks had sparked a backlash. “Today, there’s less intentional humor,” TV Guide editorialized in 1959. “Weathercasts have matured from the off-the-cuff reading of the official weather bureau reports by pretty girls to serious interpretations.”

The serious tone continued into the 1960s, when the Vietnam War and domestic turmoil made jocular reporting seem inappropriate. But goofiness returned with a vengeance in the 1970s, which brought us the now-familiar “news team” and its genial banter. Weathercasters became “television personalities” during this era, one contemporary observer wrote, “who don’t know much more about the weather than their viewers.”

They have the technology

Today, they do. Doppler radars and other new technologies allowed much more precision in weather prediction, but they also required trained professionals to interpret them. Weathercasters really do know things that laymen can’t discover on their own.

Strangely though, one-quarter of weathercasters surveyed in 2010 say the Earth isn’t getting warmer; among the rest, just one-third attribute global warming to human activities. We need to bring them up to speed, or replace them with weathercasters who are. Would we let a creationist report on geologic discoveries, or an anti-vaccinator about a polio outbreak?

But there’s more. The relaxed, cheery atmosphere of modern weather reporting prevents informed weathercasters from addressing climate change with the gravity it deserves. To be fair, some of them do mention global warming when discussing hurricanes and other emergencies. But it’s hard to find room for that when half of their air time is taken up with humorous chit-chat. And it’s hard to take them seriously when their job is to make you laugh.

Despite the recurring jibe on TV, weathercasters don’t alter climates on their own. Instead, all of us do. Nobody is better positioned to teach the public about human-made climate change than our nightly weather reporters. But we’ll have to change the climate of their reporting first.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.