Study finds regional disparities in buprenorphine distribution across Pa.

A new study found distribution of the addiction-curbing drug buprenorphine in Pennsylvania increased by 217% over the last decade.

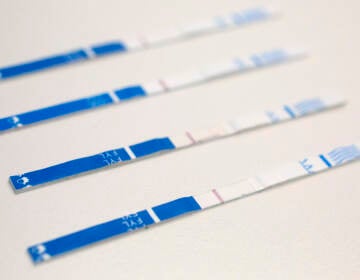

Suboxone, a branded version of buprenorphine and naloxone, is used to treat opioid addiction. (Elise Amendola/AP)

This story originally appeared on WESA.

A new study from the Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine found distribution of the addiction-curbing drug buprenorphine in Pennsylvania increased by 217% over the last decade.

Analyzing data from the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, researchers concluded distribution of the drug by weight varied greatly across the Commonwealth.

Towns within the three-digit zip code for Somerset, for instance, saw an 885% increase from 2010 to 2020. Meanwhile, in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, the jump was more modest, with increases of 228% and 79% respectively.

Since the federal government approved buprenorphine use for treating opioid use disorders in 2002, the distribution of the drug has increased nationwide. The medication — commonly combined with naloxone and sold as Suboxone — can reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings without causing a euphoric high, and is proven to help patients avoid opioid relapses.

But studies show roughly 90 percent of people with addiction get no health care at all. In recent months, the Biden administration has announced new rules through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to change that. In June, Congress passed a measure eliminating the “x-waiver,” a bureaucratic barrier that precluded many physicians from prescribing buprenorphine.

Researchers and practitioners say these reforms have made it easier for doctors in Pennsylvania to prescribe the drug to patients. That doesn’t, however, change the fact that relative to the need, there are not enough professionals prescribing buprenorphine.

“Even with the increase in [distribution in] more rural areas, there continues to be a challenge in finding providers,” said researcher Brian Piper, a professor of neuroscience at Geisinger and one of the study’s authors.

Piper said the less impressive increases in buprenorphine distribution to densely populated areas of the state were troublesome. Among U.S. counties with a population of more than 1 million people, Philadelphia and Allegheny counties ranked highest in rates of opioid-related deaths in 2016.

But Margaret Jarvis, the Chief of Addiction Medicine at Geisinger Health System in northeastern Pennsylvania, said that may have more to do with the fact that medication-assisted treatment services, like methadone clinics, were already up and running in those places by 2010—the year the study began.

Jarvis said with that foundation, the distribution of buprenorphine by weight might not have changed as dramatically throughout the duration of the study as it would in a rural area, where services were not already established at the start of the study.

Since the data is measured in kilograms of buprenorphine, and not by the number of prescriptions or patients treated, it’s hard to know just how many more people were helped as distribution increased, Jarvis added.

Still, Jarvis said urban areas must also expand access to buprenorphine, especially as the highly-potent opioid fentanyl remains “ubiquitous in the street drug supply.”

“It is really, really hard to get away from and it is so much more deadly than the other opiates,” she explained. “It means that there are people whose disease is progressing much faster than it would have if our drug supply were still mostly heroin.”

Jarvis said while efforts to increase distribution have made some strides over the last decade, there are still many barriers to access, even once patients have a prescription in their hands. Too few pharmacies in the Commonwealth, for one, carry buprenorphine to distribute to patients, forcing some patients to drive great distances to pick up their medication.

Nationally, one in five pharmacies does not carry the drug.

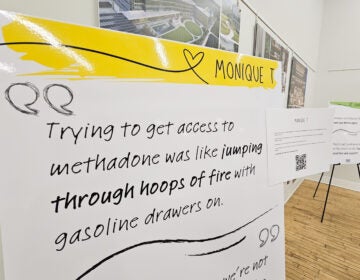

But stigma from family members and medical professionals alike remains the greatest barrier to treatment, Jarvis stressed.

Despite efforts to expand access, Jarvis said many physicians are still reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine to patients, in addition to an underlying hesitance to accurately diagnose opioid use disorders.

“Because we don’t teach our health care professionals much about this disease, it isn’t accurately dealt with by most,” Jarvis said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.