Study: Climate change will increase inequality in U.S.

In 2012, Superstorm Sandy flooded the New Jersey shoreline. (AP Photo/U.S. Air Force, Master Sgt. Mark C. Olsen, File)

Higher temperatures, rising seas, and changing weather and storm patterns are expected to increase inequality across the U.S.

That’s according to a new study that taps big data to evaluate how climate change will affect the country — county by county.

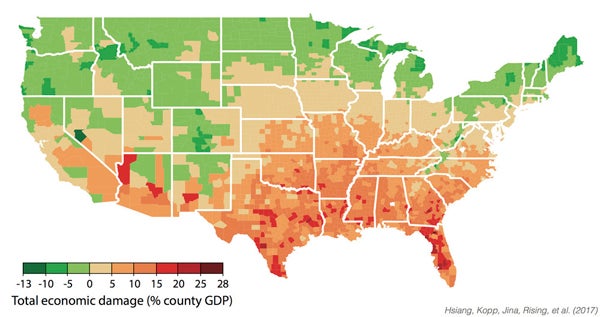

County-level annual damages in median scenario for climate during 2080-2099 under business-as-usual emissions trajectory (RCP8.5). Negative damages indicate economic benefits. “Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States” by Hsiang, Kopp, Jina, Rising, Delgado, Mohan, Rasmussen, Muir-Wood, Wilson, Oppenheimer, Larsen, Houser (Science, 2017).

Scientists counted up the costs and benefits of climate change on agriculture, crime, health, energy demand, labor and coastal communities. They found that hotter — and coincidentally poorer — regions such as the South will suffer greater damages. By the end of this century, the poorest third of counties could see damages worth 2 to 20 percent of their income if emissions don’t change, the study found.

The North could see modest benefits as energy bills go down and warmer temperatures increase agricultural output.

One of the study authors, Rutgers University’s Robert Kopp, said Philadelphia and New Jersey lie right on the border, where the South’s losses transition to the North’s gains.

The area could win some and lose some, he said.

“Here, in New Jersey and the Philadelphia area, the biggest impact of the six types we looked at is going to be due to sea level rise on coastal storms,” Kopp said. “So for New Jersey, by the middle of the century, we would project that sea level rise could lead to a doubling roughly of average annual coastal storm damages.”

The study is unique in its county-level evaluation. “That resolution is what enabled us to see some important details, like the way that climate change differentially impacts warmer, poorer parts of the country compared to cooler, richer parts of the country,” Kopp said.

It’s also unique in its application of history to predict the future. The study authors looked at how society responded to past heat waves, for example, to predict how it would respond to higher temperatures in the future.

But there are many uncertainties in the study. Steven Rose, a research economist with the Electric Power Research Institute, who was not associated with the study, said using history allows us to learn from actual — versus theoretical — behavior.

But he said it might be limited in terms of how it informs climate responses in the distant future.

“It’s making an assumption that today’s economy and population and technology are essentially also what is the economy, population and technology of the future,” Rose said. But all of those things are bound to change, Rose added, skewing the predictions.

Still, Rose said, the study has two major contributions to existing literature on the social costs of carbon. One, it’s food for thought about potential climate-related risks to the U.S. And, two, it adds new methods for estimating those risks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.