Stacks on stacks on stacks: Lessons for Philly’s public housing officials from Graduate Hospital’s ultra-modern Bloc23 project

When the Bloc23 mixed-use project from developer Stephen Rodriguez was approved by the ZBA back in 2012, Rodriguez explained that he wasn’t just out to build any old building.

“I want to shame the other developers who are ten times more financially successful than I am into doing something better,” he told Hidden City’s Nathaniel Popkin.

Rodriguez specifically criticized the Toll Brothers townhouses across the street at 2400 South, which he said looked like they were “designed by lawyers,” and when I checked in with him this week for an update on the project, undergoing site development for the past month, it was clear those townhouses still haven’t grown on him.

“If you look at 2400 South and a lot of buildings like it that are being built, and the things that are being proposed in historic locations, I mean, they’re garbage,” he said.

“2400 South has double-hung vinyl windows on a huge facade. It’s just a preposterously cheap building that in 5-10 years is going to look absurd. So we tried to do the opposite of that [with Bloc 23.]”

Designed by Campbell Thomas Architects, the Graduate Hospital firm best known for their preservation and trail planning work, and Stephen Nebel of the Berlin firm LABhaus, Bloc23 boasts 22 units with a 10,000 square foot retail space and green design features.

Rodriguez says the team made the retail space the main focus of the building, with the pedestrian experience as the primary design consideration.

“If you look at the way our retail is laid out, we went to the trouble of making this a functional neighborhood building, and not just a generic can that doesn’t interact with the neighborhood in any way.”

Another novelty about this building is that it’s being built in a factory.

Rather than being constructed from scratch on-site like most buildings, Bloc23 will be put together off-site as a series of boxes, which will be shipped to the building site at 23rd and Bainbridge and pieced together there.

There are still about three months of site work to do before they erect the steel, and ultimately drop the boxes into place about five months from now. It’ll then take another two months to stitch them up, and the building should be complete by early next year.

Modular construction is still something of a novelty in Philadelphia, though it has become much more common in recent years. Diamond Green and The Modules near Temple and the Flats at Girard Point in Northern Liberties are some notable examples.

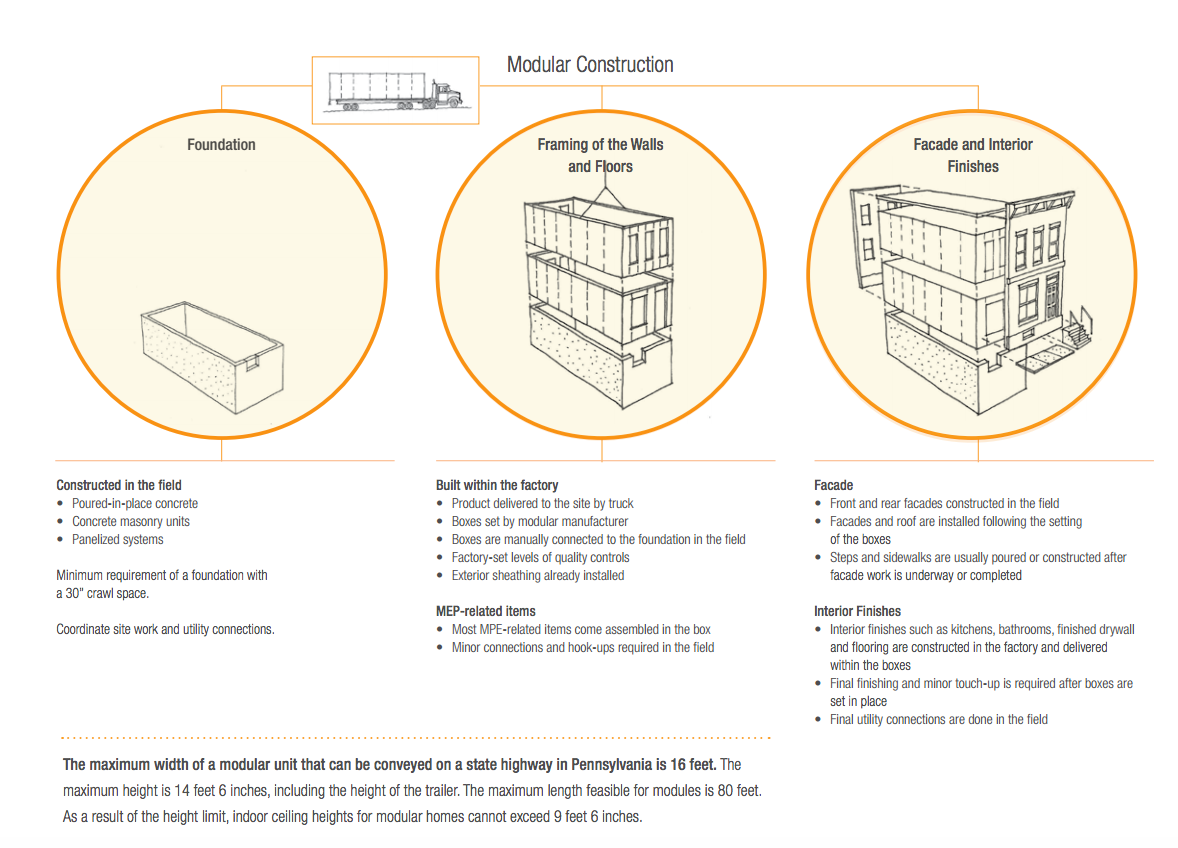

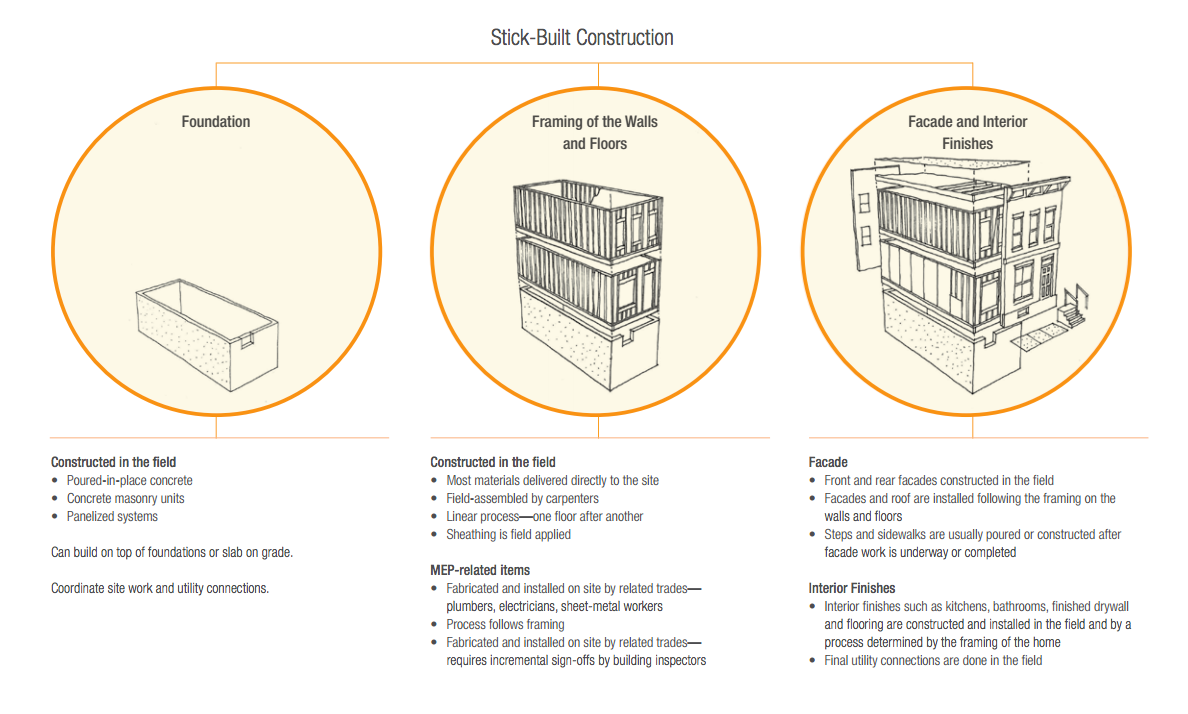

A 2010 report called Going Mod: Reducing Housing Costs in Philadelphia with Modular Construction, released by the Building Industry Association and the When We Fix It coalition contains some great illustrations that demonstrate the difference between modular and traditional construction:

Rodriguez says Bloc23 will take about six months less to build than the time it would take to construct a project of this size the traditional way, saving a lot of money.

“Your site conditions, your interest reserve–you save half a year’s worth of time so it’s a huge savings,” he said, “Hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions.”

The Going Mod report confirmed that savings can be substantial. They found that modular construction of a 16-foot-wide house in the city reduced square-foot costs by $32 (about 20%), or $12 a square foot (about 9%) for a 20-foot-wide house.

Modular doesn’t work for all types of buildings, and is actually better suited to larger multi-unit projects. Though 16 feet is the maximum allowed width that can fit on a Pennsylvania highway during transport, Rodriguez says the maximum width you can order is 15.5 feet, which is half a foot shy of a standard city lot.

So unless a developer is building on multiple contiguous lots, it doesn’t lend itself to one-off projects.

Besides the direct cost and time savings advantages, there are also some key quality advantages to building indoors, like protecting materials from the elements.

“The [Toll Brothers] building across the street is a perfect example,” Rodriguez said, “It’s about four times the size by volume, and it took them almost a half year from the time they got started to when the roof went on, and during that time it’s just getting dumped on by the rain and weather.

“Especially with modern dimensional lumber, which is primarily new-growth pine, it absorbs a ton of water. And what will happen over time is you’re going to get warping as all that moisture just gets soaked up by the wood. That can throw off your tolerances, create nail pops, and all manner of issues.”

So given all these benefits, why aren’t we seeing more developers taking advantage of this technology? Rodriguez gave three of the major reasons.

Most significant are the dimensional constraints. I mentioned the highway rules and lot sizes already, but building in the city in general is also a challenge because typically you can only access the site from one side, which is a challenge for dropping in the boxes.

Another issue is the more complex logistics. Rodriguez said the timing needs to work out just right so that the pods are completed at the factory precisely at the time they’re ready to be installed on the site.

“One thing we came to appreciate was when you’re doing modular, everything’s double,” he said, “You have two architects, two engineers, multiple NEPs–in terms of involved parties, there’s far more people than when you do it stick-built.”

A third issue is the difficulty in finding a lender who is comfortable financing modular projects. Commercial lenders tend to be very risk averse, and because modular makes up such a small portion of the buildings that are constructed, they tend to shy away from them because they have less familiarity and experience with them.

Rodriguez is working with DNB First Bank, a local bank with branches in the suburbs, on Bloc23. They had some experience with modular projects and believed in the concept. PIDC also provided gap financing for about 10% of the deal.

These are some of the reasons why private developers don’t take advantage of the cost and quality advantages. But what about the public sector?

The city of Philadelphia spends a lot of money on construction subsidies for affordable housing, so one might wonder why we aren’t taking advantage of these cost savings to deliver more housing units for the same money.

As with any change, there would be a learning curve for mastering a new process. But the bigger issue there seems to be more political.

There is intense political interest around who gets the public money spent on housing, and former Redevelopment Authority director Jay McCalla recently argued in a Citified op-ed that the constellation of service providers presently drawing on this money make up an “affordable housing industrial complex” whose lobbying heft takes cheaper affordable housing strategies out of consideration.

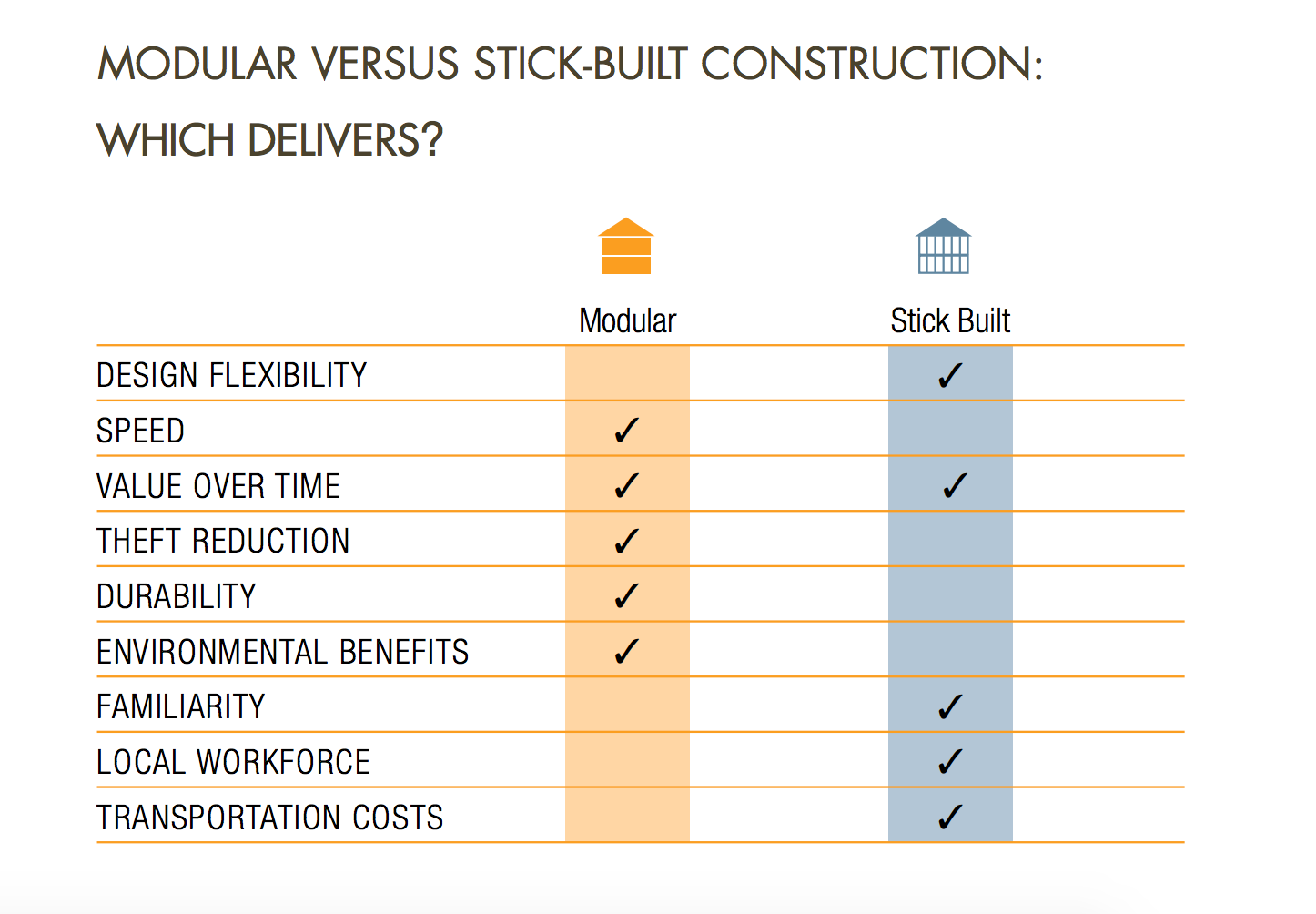

Though the powerful building trades unions are one of the parties McCalla includes as part of this complex, the issue isn’t really about unions so much as it’s about local vs. out of town labor.

The Going Mod report gets at this in their chart comparing the advantages and disadvantages of modular vs. stick-built construction:

As one of their recommendations, they suggest a concerted effort to attract a modular factory to the city for two reasons, one of which is the jobs piece.

“If more builders chose modular housing methods, it would create an inducement for factories to open in or near the city,” they write, “helping Philadelphia to create new jobs and to achieve many of its sustainability objectives by reducing the carbon footprint of home construction … . Having a manufacturer in or nearer to Philadelphia’s borders would allow for the training and hiring of more Philadelphia workers, particularly minority workers, who currently are underrepresented on union construction-site crews.”

The other reason is that locating a modular housing factory in the city would allow houses to be transported using only local roads. That would get around the dimensional restrictions that come with highway transport, and allow for the creation of larger modular buildings.

“Modular builders in the state are currently limited to shipping boxes no wider than 16 feet on state highways. One builder has found a way around these restrictions in New York City—by shipping exclusively on local roads and obtaining an agreement with the city that allows the transportation of wider boxes. New York City, in order to bring down the cost of constructing affordable housing, has authorized the shipping of 18- and 20-foot-wide boxes on local roads between midnight and 4:00 a.m. This allows for larger homes to be built using a single box.”

Modular construction is far from a silver bullet for lowering Philly’s housing prices, but at a time when there is heightened interest in boosting the supply of inexpensive housing in the city, it’s an innovation that probably warrants a closer look from housing officials in the next administration.

Read the full report for a more in-depth treatment.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.