South by Southwest: how Center City’s relentless expansion remade a historic neighborhood

The transformation of Southwest Center City from one of Philadelphia’s most blighted and crime-riddled neighborhoods to one of its most desirable is nearly complete.

On some blocks, luxe town homes now list for over $1 million. Contractors clog the streets, working dozens of active construction sites. Perhaps most telling is this remarkable stat: the neighborhood’s stock of abandoned homes and vacant lots – which numbered at least 554 in the late 1990s – has dwindled to about 80 [pdf].

“We have become kind of a poster child for gentrification,” said Andrew Dalzell, program coordinator for the South of South Neighborhood Association, or SOSNA. “For better or worse, at some point developers looked at this neighborhood and just saw dollar signs.”

It is not hard to understand why: location.

From SOSNA’s headquarters at 19th and Christian Streets, Rittenhouse Square lies just a half-mile away, and the office towers of Market Street stand just a few blocks further north. Once construction on the South Street bridge is finished later this year, a 10-minute stroll will take residents to the University of Pennsylvania, the city’s largest employer.

The reporting of this article was funded by a grant from the William Penn Foundation. It is the first in a series of PlanPhilly stories that will explore the dynamics of two redeveloping Philadelphia neighborhoods, Southwest Center City and Eastern North Philadelphia.

“A friend of mine likes to say that Center City’s edge is wherever people will pay Center City prices for a home. South Street used to be that. But in reality now that line is Washington Avenue,” Dalzell said.

The median sales price of a single-family home in Southwest Center City is now $282,000, a staggering 526 percent increase in just 12 years. A residence in this neighborhood – which stretches from South Street to Washington, and from Broad to the Schuylkill – now costs nearly 2.5 times as much as the average Philadelphia home.

“The biggest factor is location. It was people wanting to live in or near Center City, but not being able to afford property north of South Street,” said Terry Gillen, Executive Director of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority and a longtime resident of the neighborhood.

Yet location alone does not tell the whole story of Southwest Center City’s transformation.

In a perverse way, the neighborhood’s wretchedness in the 1980s and 1990s served to set up its redevelopment. Blight, crime and abandonment had depressed property values in Southwest Center City to absurdly low levels for an area so close to Philadelphia’s wealthiest neighborhoods. That created opportunities for developers to buy empty shells at remarkably low prices, refit them with granite countertops and make a handsome profit on the deal.

In 1998, John Kromer – then head of OHCD – led a city survey of abandoned properties in Southwest Philadelphia. Ten years later, Kromer organized a second neighborhood vacancy survey through the Fels Institute of Government at Penn. He updated that survey’s findings at PlanPhilly’s request. Kromer is now working on a similar study examining Eastern North Philadelphia, an area that has been extensively redeveloped by Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha.

Non-profits such as SOSNA played an important early role in nurturing development. And recording legend Kenny Gamble’s investments through the non-profit Universal Housing likely accelerated the neighborhood’s redevelopment.

Public policy was instrumental too. City agencies funneled federal block grant money to the neighborhood in the 1990s. And developers say the city’s 10-year tax abatement stimulated redevelopment as well.

“The location was critical. The unexpected success of Center City was critical. The tax abatement just happened to become available as the real estate market was improving,” said John Kromer, a former director of the city’s Office of Housing and Community Development, who has studied vacancy trends in Southwest Center City. “All of this made it possible to achieve a lot very, very quickly.”

PlanPhilly’s video overview of the changes in Southwest Center City. Story continues below…

The Reinvention

Patrons leave the Sidecar bar located on 22nd and Christian Streets.

The remaking of Southwest Center City is easy to see on the stretch of Christian Street between 20th and 22nd.

At one end sits the Sidecar Bar, one of the neighborhood’s four gastropubs.

Adam Ritter bought the space in 2005, when it was a dive bar called “Victor’s Tavern, A Place for Good Folks.” While renovating the place, Ritter said he found packets of crack cocaine secreted away beneath bar stool covers.

“It was a nuisance bar, a pretty unsavory place,” Ritter said. “But it had some really cool soul to it.

For six months, Ritter and his wife ran the bar as Victor’s, getting to the know the clientele and the neighborhood.

“The dynamics of the crossing of cultures and personality were outrageous. I mean, I’m this little white kid in this shot and beer black bar,” Ritter said.

Then Ritter and his wife renovated, and gradually began offering more sophisticated food and drink, alongside cheaper “burgers and suds” so as to smooth the transition from “dive bar to some yuppie place.”

Now, though, the Sidecar bears little resemblance to Victor’s, with its sidewalk seating, boutique beer list and a menu with upscale touches like vegetable risotto with tomato fennel broth and a parmesan tuile.

Late last Sunday afternoon, the Sidecar Bar was jammed. There was a pair of old heads, with calf-high white socks and sneakers, drinking beer at the bar. But the crowd was dominated by the neighborhood’s new arrivals, who are mostly young, mostly childless, and mostly white.

A block away, Rev. Charles McNeil led his dwindling African-American congregation in prayer at Shiloh Baptist Church, an enormous compound built in 1870 by the renowned Philadelphia architecture firm of Fraser, Furness & Hewitt.

McNeil was raised a block away from his church, and he has worshipped at Shiloh since 1975.

But the church today is not the church he grew up with.

Southwest Center City is a neighborhood with many names. Some call it Graduate Hospital, or G-Ho. Others label it South of South. Long-time residents generally call it Southcentral, or simply South Philly.

For one, regular services are no longer held in Shiloh’s main chapel. The pews inside that huge hall are draped in plastic sheeting. The room smells of mildew, and parts of the roof are blackened by water damage.

McNeil is trying to raise money to plug the leaks. He reckons it will take $100,000 to finish the job.

“If you’ve got some laying around we’ll gladly accept it,” McNeil tells a visitor.

But today’s congregation might seem out of place in the enormous sanctuary, even if the roof were in perfect order.

Back in its 1950s and 1960s heyday, Shiloh’s congregation was 4,000 strong. Today the church has just over 100 members, McNeil said.

McNeil, who has a doctorate in ministry from Palmer Theological Seminary at Eastern University, chose for his dissertation a subject close to his heart: the plight of black churches struggling to stay vital in gentrifying neighborhoods.

One of his ideas for Shiloh is to rent out the massive facility – it covers half a city block – for community events, be they fitness classes, or parties. Anything, really, that will keep the church solvent and relevant.

“The fear is this becomes a museum. A used-to-be. We don’t want to be a used-to-be place,” McNeil said, as he opened the door to a huge Shiloh gymnasium that once thronged with neighborhood kids but is now used to store equipment from another struggling church.

When asked what he makes of the radical changes Southwest Center City has made in recent years, McNeil answers: “we need to be honest about what we mean when we say ‘change.'”

In this case, he says, “change” means the transition from a black, working class neighborhood to a middle-to-upper class white neighborhood.

“It is what it is. Some things you are not going to be able to stop. The reality is I can’t change it. No one in this church can change the transitions that are taking place in this community,” McNeil said.

Those transitions include the departure of many long-time neighborhood residents – there is no data available to show how many – who were simply displaced by rising rents. Others who owned property have cashed out, selling their homes and making a nice profit before moving on.

Many, though, have stayed. And in McNeil’s view, the tensions between new residents and old, between black residents and white, have not entirely eased, at least not yet.

“I don’t think things have calmed down,” McNeil said.

As if for emphasis, he compared long-time Southwest Center City residents to the landowning peasants Che Guevara encountered in his early days as a Communist revolutionary.

“I can probably equate it to those South American communities that were bulldozed. The companies just took what they wanted to. He fought for the farmers and workers to keep their lands but they still bogart their way in,” McNeil said.

An abandoned shell sits next to redeveloped houses along 21st and Christian streets.

It is a point of view Terry Gillen understands, even though she does not think gentrification tensions have ever spiraled out of control in Southwest Center City. Early new arrivals to the neighborhood “were pretty respectful of the traditions of the neighborhood they were moving in to,” she said.

Eventually, though, that changed a bit, Gillen said.

Developers began building homes with street-level garages and huge roof decks. The properties attracted buyers with a “quasi-suburban mindset,” Gillen said.

Gillen recalled one morning where she met a woman on Christian Street with an SUV parked in the driveway of her newly renovated rowhome. She was near tears, Gillen said, “because her new neighbors were out late at night, and she didn’t really feel safe.”

“I looked at her and thought, ma’am, did you think you were moving to Chestnut Hill,” Gillen said.

Some long-time residents have met the neighborhood’s changes with a kind of dogged determination, vowing never to leave.

“I am here for the duration. I am not going anywhere,” said Barbara Williams, a church secretary who has lived in the neighborhood her entire life. “I’ve had all kinds of offers from different realtors. Every other week somebody was sending me something.”

When asked why land speculators targeted her, Williams replied that it was not difficult to figure out that her home on the 2200 block of Bainbridge was not renovated.

“I don’t have the money to spend $50,000 on the front of my house, as much as I’d like to. So I’m easy to identify, and probably some of my neighbors look at my house and say, ‘oh, why is she still here?'”

“But when I go it will be to see the maker, not because somebody forced me out.”

PlanPhilly’s interactive map showing the neighborhood’s redevelopment. Story continues below….

The Decline

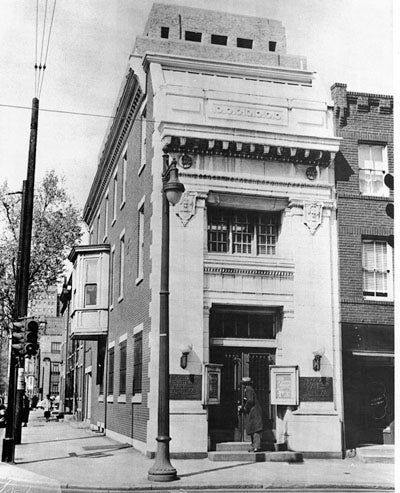

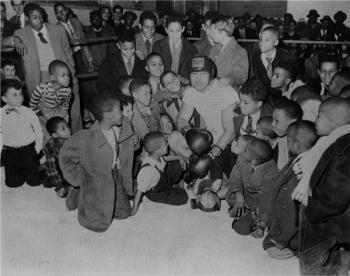

The Christian Street YMCA. Photo by John W. Mosley

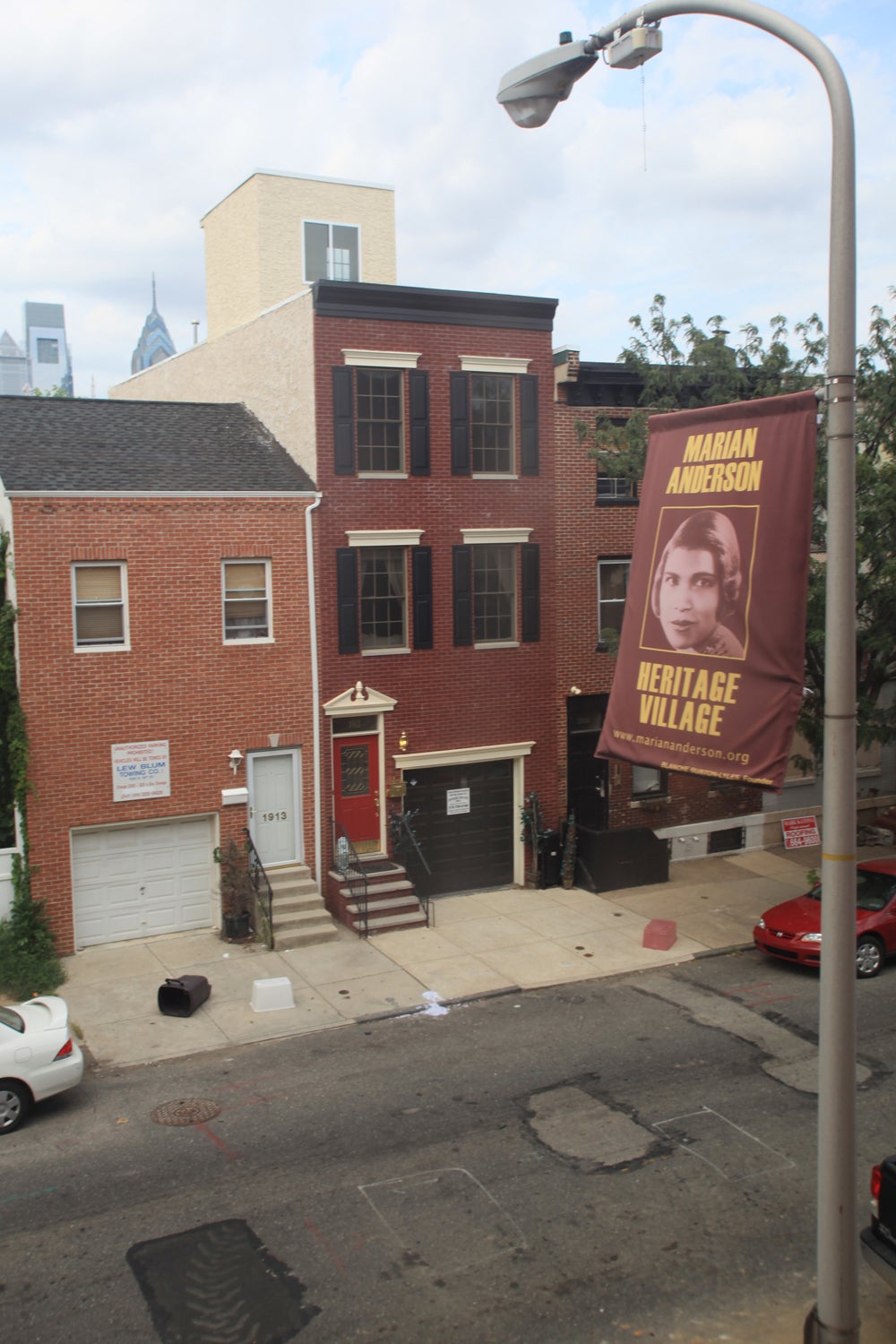

For decades, Southwest Center City was the cultural and economic center of Philadelphia’s African American community. At the neighborhood’s peak, nearly 30,000 people lived in its rowhomes, including such pioneering cultural luminaries as the contralto Marian Anderson and the architect Julian Abele.

Dentists, lawyers and other professionals filled the grand homes of Christian Street, which was known then as “Doctor’s Row.” The boulevard’s YMCA was a magnet for world-renowned athletes such as Joe Louis and Joe Frazier.

Local jazz clubs – including the Royal Theatre at 15th and South – featured performers like Fats Waller and Cab Calloway, while the likes of John Coltrane and Nina Simone joined a union of African-American musicians headquartered on Broad Street between Christian and Carpenter.

“From City Hall’s perspective back in the 1920s and 1930s this neighborhood was a lost cause. But in reality it was a vibrant, vibrant community that was extremely self-sufficient,” said Dalzell, who is working on a short history of the neighborhood for SOSNA.

“It’s a shame that went unacknowledged, except for by the people who lived here, for so many years.”

But like so many other Philadelphia neighborhoods, Southwest Center City declined sharply during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

The most direct cause was likely the departure of affluent African American professionals, who decamped for the suburbs or more spacious homes in Mt. Airy and Germantown.

But there were institutional forces working against the neighborhood as well.

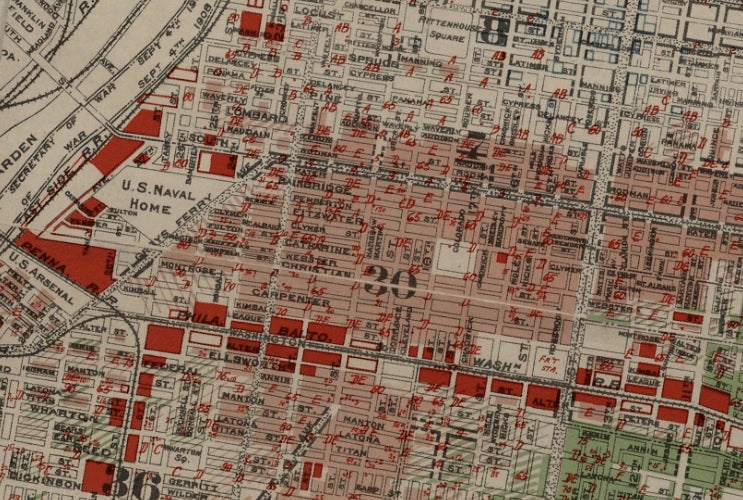

Private lenders and the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation redlined the neighborhood, labeling it “hazardous” to investment, thus making it extraordinarily difficult for would-be homeowners to secure loans for properties in the neighborhood.

And there was the looming specter of the “The Crosstown Expressway,” a sunken, eight-lane behemoth taken straight from the now discredited urban renewal playbook that would have obliterated South Street.

Although the project – which had been on the drawing board in one form or another since the 1930s – was ultimately abandoned, it created prolonged uncertainty over the neighborhood’s fate, and further discouraged investment in Southwest Center City.

There was little to no help from City Hall, either, said Kromer, who entered public service in 1992 at the beginning of Ed Rendell’s first term as mayor.

J.M Brewer’s 1934 map shows appraisals of property risk, marked in red, in Southwest Center City | Image Credit: Philadelphia Geohistory Network / Map Credit: Free Library of Philadelphia

“At that time, the view of Philadelphia’s city government, which was consistent with that of other city governments, was vacant houses and lots are not our problem. We don’t own most of them, and we don’t have the money to fix them all up,” Kromer said.

By 2000, the area’s population had dwindled from an early 20th century peak of about 30,000 to 10,624.

Many of those that remained had no other options.

“That was my family,” McNeil said. “We weren’t financially able to move, and I’m not sure if we ever desired to. But those who stayed saw the introduction of crime, of drugs.”

In 1998, the same year Kromer’s city survey found 554 abandoned homes in the neighborhood, crime rates in Southwest Center City were well above the city average in virtually every category, from aggravated assaults and robberies to quality of life crimes such as prostitution and disorderly conduct.

And yet, as hard as it was to imagine at the time, Southwest Center City’s redevelopment was already underway.

The Organizations

In the 1970s, moved by the decay of the neighborhood where he was born and raised, Kenny Gamble bought his childhood home at 1442 Christian Street for about $1,500. Like so many properties in Southwest Center City at the time it was an abandoned shell.

Gamble had moved out of the area years ago. He bought a mansion in Gladwyne. But he kept making brief drive-by detours to his old neighborhood while commuting to his office at Broad and Spruce.

“Year after year, it was getting worse and worse. All the abandoned houses and drugs and hopelessness,” Gamble said.

After he bought his childhood home, he tried to give it to his mother. She refused.

“She said ‘I don’t want it. There’s a lot of bad memories there,'” Gamble said.

But Gamble would go on to buy out much of the rest of the block. Eventually, he formed a non-profit commercial development company, Universal Community Homes, which built 32 rental residences on the blighted block where Gamble grew up.

Over time, Gamble and Universal would acquire more than 120 properties in the neighborhood. Most of them have been redeveloped.

Yet the organization has been a source of controversy in Southwest Center City.

Some feel the non-profit has moved too slowly to develop some of its properties, such as the historic Royal Theater at 15th Street and South. And a few private developers grumble that the organization got city land on the cheap, due to Gamble’s political connections.

But there is little doubt that Universal investments played a critical role in speeding up the redevelopment of Southwest Center City, particularly given the non-profit’s focus on the area near 15th and Christian, which was perhaps the most blighted section of the neighborhood.

Houses along Madison Square in the Southwest Center City area of Philadelphia.

“Universal was very important,” Kromer said. “Other sections of Southwest Center City had problems, but I think it’s accurate to say that the highest concentration of those problems – the physical deterioration, crime and social problems – was in that area (15th and Christian). So it was serendipitous that happened to be the area where Mr. Gamble had grown up.”

Over time, Universal’s mission expanded into education and social services. Kromer contends that those efforts further opened the door to private investment in the neighborhood.

“The idea that the organization would not just focus on bricks and mortar but also on the need for human capital development as well as real estate development was very sophisticated,” Kromer said. “They were not the only Community Development Corporation that took that view, but they were certainly more ambitious and more successful than most other organizations that were active in that time.”

Kromer also credits SOSNA with helping prime the pump, not so much through its own developments, but by luring builders to the area before the full-fledged redevelopment rush was on. By then, City Hall had begun to view the problem of abandoned properties a bit differently, and had started looking for competent local organizations like SOSNA to partner with.

“It was only during the decade of the 1990s that most cities understood that these properties were not going to take care of themselves and regardless of the degree to which the city was or was not responsible for them, they were a critical challenge that had to be part of the city’s agenda,” Kromer said.

“That change in thinking was really fundamental and it took a decade for many large post industrial cities to get there.”

In 1995, at a time when private investment in Southwest Center City was almost non-existent, SOSNA teamed up with the city to build the Artists Village apartment complex on 17th Street.

A few years later, the organization again partnered with City Hall to rehab 10 affordable duplexes on the old “Doctor’s Row” section of Christian Street. And in 1998, SOSNA secured city funding to convert a shuttered parochial school into housing for seniors.

PlanPhilly’s interactive graphic about Southwest Center City housing values. All data is drawn from quarterly indices created by Kevin Gillen, an economist with Econsult. Story continues below….

The Redevelopment Rush

Though it would be a few more years before the frenzied redevelopment phase began, it is clear looking back that the tide in Southwest Center City turned sometime during the late 1990s.

Home values in the neighborhood jumped 10 percent in 1997, 20 percent in 1998, and 30 percent in 1999. That growth was nearly eight times as robust as the Philadelphia average over the same period.

Then, in 2000, the city extended its 10-year property tax abatement program to cover new construction, not just renovations, further setting the stage for Southwest Center City’s boom.

Three years later, Toll Brothers won city approval for a $100 million plan to build up a small city of luxury condos and town homes at the old Naval Home at 24th and Bainbridge. The magnificent Biddle Hall and 20-acres of surrounding grounds had languished largely unused (with the exception of squatters) since 1976, when the Navy relocated its retirement home for old sailors to Mississippi.

Once Toll Brothers started pre-selling units in the massive new development for $300,000 and more, smaller developers smelled opportunity, and moved in on Southwest Center City en masse.

Toll Brothers’ Naval Square, a gated community consisting of townhomes and condominium units.

“Once Toll Brothers broke ground, it was pretty evident what was going to happen,” said Steve Shklovsky, a partner with Metro Impact, which has bought, developed and sold about 40 properties in Southwest Center City since 2005.

Block by block, small-scale developers like Metro Impact marched deeper into the blighted neighborhood, beginning with the streets immediately below South Street, then Christian, then Carpenter, and now to the blocks beyond Washington Avenue.

“Developers usually work like that,” Shklovsky said. “They see that somebody sold something on one block. They see the comps, and then they start working around that area. It just takes someone willing to go first.”

During the housing crash a few bigger players like the Toll Brothers stalled projects in Southwest Center City.

But smaller builders kept working. And they kept making money.

“If you can acquire the lots at the right price, and you aren’t too greedy on the sales price there’s been no issue, not in this neighborhood,” Shklovsky said. “In the past year and a half we’ve had everything under contract within three weeks.”

Kromer’s vacant land studies bears that out. For instance, his Penn survey team found 114 abandoned buildings and vacant lots in the neighborhood in 2008. Two years later, that number had dwindled to 80. And of those, 50 are already owned either by developers, the Philadelphia Housing Authority, or the City of Philadelphia, a PlanPhilly review of property records found.

Many of the city-owned properties are clustered on the 1000 block of S. 17th Street, just north of Washington Avenue. The RDA wants to sell the land, Gillen said, but has so far been unimpressed with the bids it has received from larger developers. She blames the scarcity of financing for big housing projects in the post-bubble era.

Now the agency is trying to determine if it should sell its holdings off in smaller parcels to small builders, Gillen said.

That would suit Shklovsky just fine. He wants the city to unload fast, and let developers like him finish the job of remaking Southwest Center City.

“Just give it a little more time, and things like these bodegas, this laundromat, will be gone,” he said, as he walked along the 2100 block of Christian Street, pointing out some of the neighborhoods older businesses.

Then he gestured at the Sidecar Bar.

“Get a couple more Sidecars in here. A Starbucks would be beautiful. A Tria. You know, stuff like that,” said Shklovsky, who plans to soon move from his home in suburban Bucks County to Southwest Center City.

The Future

The next redevelopment frontier is south of Washington Ave., pictured here.

Shklovsky’s vision is likely not far off. Retail development in the area has lagged behind residential growth, but SOSNA hopes that will change soon, perhaps with the reopening of the South Street Bridge.

“You’ve got a lot of rich 25 to 35 year olds moving in. So you’ve got more people here, and the average income is gradually increasing, so there’s a lot of money to be spent,” Dalzell said.

After that, the next redevelopment frontier is nothing less than Washington Avenue, a four lane quasi-industrial boulevard lined on both sides with home supply warehouses.

Already there are tentative plans to convert the hulking, long empty Frankford Candy Factory at 2101 Washington Avenue into a mixed-use facility with ground floor retail. And other developers are quietly exploring other Washington Avenue projects, Shklovsky said.

“I think most of those supply companies are going to get out of there at some point,” he said. “I don’t know if it’s going to be five years, or 10 years, or 20 years. But it will happen. Somebody’s just got to start it off.”

Whether the redevelopment wave crosses Washington or not, it has already irreversibly changed Southwest Center City, and not entirely for the better, Pastor McNeil said.

The falling crime rates, the eradication of blight, they do not completely make up for the loss of a sense of community, McNeil argued.

“When I was younger, everyone knew everyone. There was not a person around here who didn’t know one another. Therefore they watched out for one another. They assisted one another,” McNeil said. “Now, most feel like they’re strangers to one another, and you dare not say too much to them.”

But it is worth remembering that the community McNeil mourns was a shadow of its former self long before the gentrification of Southwest Center City began.

And ultimately, there is the immutable, unavoidable fact that a blighted neighborhood so close to the penthouses of Rittenhouse Square was destined for redevelopment.

“For me, embedded in the definition of neighborhood is change,” said Dalzell of SOSNA. “Trying to preserve a neighborhood as it was at one time, it’s a futile cause. And I don’t think it’s a worthy one.”

Project reporter Patrick Kerkstra can be reached at pkerkstra@planphilly.com

Photos by Neal Santos

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.