Some Jersey Shore businesses say $15 minimum wage would be devastating

Businesses in several summer resorts want to carve out an exemption for seasonal workers.

The Jersey Shore employs thousands of seasonal workers each summer. (Bill Barlow/for WHYY)

As of January, New Jersey’s minimum wage has increased slightly, to $8.60 an hour.

At 40 hours a week, that’s $344 before taxes, and worker’s advocacy groups say that is nowhere near enough to live on, even for a single adult with no children. With a new governor and a Democratic majority in Trenton, most expect a bill again increasing that minimum to be approved by the end of the year.

Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy wants to see $15 an hour. Senate President Stephen Sweeney said talks are underway on how best to get there. A $15 an hour minimum wage would generate $600 per week.

In a recent interview, Sweeney said he’s meeting with business organizations to find a way to increase pay for all workers without tanking New Jersey’s economy in the process.

That could include exemptions for the youngest workers. Any increase is expected to be phased in over a period of years. Sweeney seems certain that a $15 minimum is on the way. So do business groups, as well as advocates for workers.

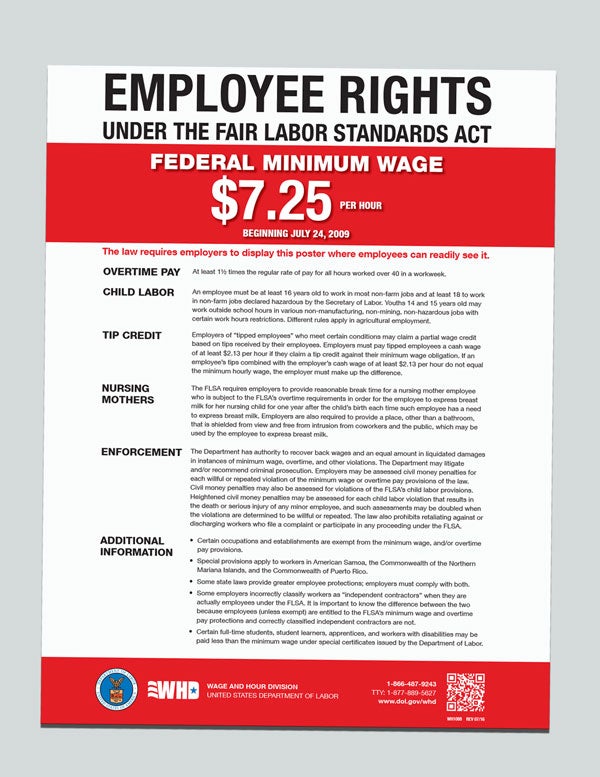

Minimum wage comparison

- New Jersey $8.60 $17,888 per year

- Pennsylvania $7.25 $15,080 per year

- Delaware $8.25 $17,160 per year

- New York $10.40 $21,632 per year

But some businesses at the Jersey Shore warn that a $15 minimum wage could be devastating.

“It would force us in the short-run to try to increase prices across the board,” said Scott Simpson, the owner of Playland Castaway Cove amusement park on the Ocean City boardwalk. Customers may decide a night at the rides with the family is not worth the increased cost.

“I’m not the government,” Simpson said. “If you get a tax bill, you have to pay it. You don’t have to come here.”

In fact, numerous business organizations and chambers of commerce leaders throughout the state are already working hard to blunt the impact of a possible minimum wage hike. The Cape May County Chamber of Commerce, representing businesses in several summer resorts, wants to carve out an exemption for seasonal workers. The group is working with local lawmakers on the best way to do that.

“Fifteen dollars an hour is very high for the average Cape May County business, especially for those seasonal businesses,” said Vicki Clark, the president of the Cape May County Chamber, saying it’s even tougher for small businesses that make most of their money in the brief summer season.

Tourism is big business in Cape May County, bringing in more than $6 billion a year. Still, most businesses on the boardwalks and throughout New Jersey’s beach towns are family-run and typically operate on narrow margins. They need to make most of their money in June, July, and August. According to Clark, a bump in the lowest pay would probably mean hiking wages for more experienced workers as well, so that an experienced return employee won’t make the same amount as someone who just walked in the door.

“I think it would be extremely cost prohibitive to provide a family-friendly destination at a cost that the average family could afford with payroll costs close to doubling,” Clark said.

Exempting seasonal workers may not do the trick, argues Simpson. If a teenager can make $9 an hour on the boardwalk and $15 working at a year-round fast food place, it will be tough to fill any summer job, he said.

“No one will come work for us on a seasonal basis for their first job,” he said. He believes workers should see more money, but does not think it makes sense to start a teenager off at $15 an hour when they have no work experience.

Brandon McKoy argues that the distinction between young and old workers or between seasonal and year-round workers is based on antiquated notions of work and of workers. McKoy is the director of government and public affairs for New Jersey Policy Perspective, an organization that has advocated for increasing the minimum wage.

“Doing a job is doing a job,” he said. “If we want to ensure that work is valued, we’ve got to actually reward work. I don’t like separating out seasonal workers from other types of workers.”

At a time when society is pushing back against inequality in pay between the sexes and age discrimination is illegal, McKoy described the idea of paying someone less based on how long he’s been alive as “dissonant.” Many young workers contribute heavily to their families’ living expenses, he said, and college students typically need to make money in the summer to keep up with exorbitant tuition costs. For most student workers, the summer job at the shore fit in around the house parties is a thing of the past.

According to McKoy, a serious change to the minimum wage is overdue.

“What we know of the current cost of living in New Jersey right now is that there is no part of the state in 2018 where a single worker can get by on less than $15 an hour,” he said.

State Sen. Jeff Van Drew, a Democrat representing several shore towns, said he is working with Sweeney to find the right balance to improve the lives of the state’s lowest paid workers without damaging the economy.

“What we don’t want to do is create a situation where we have less jobs,” Van Drew said. “I don’t want people to lose their jobs. If you don’t think that can happen – you’re wrong.”

For now, there is no bill in the Senate or Assembly. Sweeney said he would have liked to have something on paper by now so workers could start to see a difference starting in January 2019. But he, too, said it’s important to move carefully. Sweeney sponsored the last two bills to increase the minimum wage and he plans to sponsor this one as well.

He’s amenable to compromise on seasonal workers and exemptions for teenagers, saying “for kids 16 to 18, you don’t need the $15 an hour.” Even phasing in the increase over years, he described $15 an hour as a big jump.

“This isn’t a dollar or two. This is close to double the current minimum,” he said. As Sweeney put it, about nine out 10 small businesses close. “I don’t want to do anything that’s going to make 10 out of 10 fail.”

Move too quickly, he said, and businesses will move toward automation. That could include everything from grocery stocking to fast food checkout stations, potentially making entry level jobs almost impossible to find. Even if everything is done very, very well, he said, the change will probably cost some jobs. The plan is to have it add more better paying jobs than the number lost.

McKoy sees some of the worry as short-sighted. Better paid workers will spend more, save more, and can take more trips to the shore. Helping the most economically insecure workers will help the entire economy, he argues.

“They don’t anticipate how much more revenue increased wages will bring in,” he said. “All they’re seeing is how much their labor cost is going up.”

Van Drew expects to see a bill ready for a vote before the end of 2018, with the wage increase phased in over a period of several years. Gov. Murphy has backed the increase, both during the campaign and in repeated public statements. Sweeney said his office is working closely with Murphy’s administration, describing the wage increase as a priority for the new Democratic governor.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.